On September 23, 1990, Ken Burns’ mini-series documentary, The Civil War, made its debut on PBS. It would become immensely popular and was the subject of workplace “water cooler” conversations across the nation during its initial airing that fall. However, there was one moment that defined the series, and which fired the imagination and touched the hearts of viewers across the nation. That moment occurred at the conclusion of the first episode, when narrator David McCullough introduced Paul Roebling’s reading of a letter, written by an obscure volunteer major from Rhode Island to his wife. Within minutes, as the closing credits were still rolling, phone lines at virtually every PBS station lit up, as thousands of viewers called. They all wanted to know if the letter that they had just listened to was real, and, if so, who was this man who had written something so wonderful. Many described the letter as the most “romantic” they had ever heard. For me, however, this remarkable letter has become far more than merely “romantic.”

On September 23, 1990, Ken Burns’ mini-series documentary, The Civil War, made its debut on PBS. It would become immensely popular and was the subject of workplace “water cooler” conversations across the nation during its initial airing that fall. However, there was one moment that defined the series, and which fired the imagination and touched the hearts of viewers across the nation. That moment occurred at the conclusion of the first episode, when narrator David McCullough introduced Paul Roebling’s reading of a letter, written by an obscure volunteer major from Rhode Island to his wife. Within minutes, as the closing credits were still rolling, phone lines at virtually every PBS station lit up, as thousands of viewers called. They all wanted to know if the letter that they had just listened to was real, and, if so, who was this man who had written something so wonderful. Many described the letter as the most “romantic” they had ever heard. For me, however, this remarkable letter has become far more than merely “romantic.”

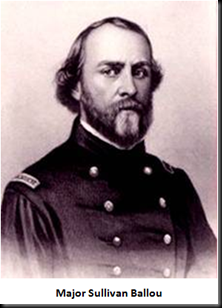

The letter was penned by Sullivan Ballou, a major in the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry Regiment, just one week before the first Battle of Bull Run. Ballou was a lawyer and member of the state legislature from Smithfield, Rhode Island. He had grown up in Smithfield and, having lost both his parents at an early age, struggled to both fend for himself as a child, and make something of himself as a young man. But, he certainly succeeded at both, successfully graduating from Brown University and then entering the Rhode Island Bar in 1853.

In 1855, Ballou married Sarah Hart Shumway, a young lady of 19, described as intelligent and “proper.” Their first child, Edgar Fowler Ballou, was born in August 1856 and, two years later, a second son, William Bowen Ballou, would follow. Sullivan and Sarah’s marriage was, by all accounts, a very happy one, and Sullivan’s career was extremely promising. By the time the Civil War broke out, he was 32, had a prosperous law practice, and was already a former speaker of the Rhode Island House of Representatives. But, Sullivan Ballou was also an ardent supporter of Abraham Lincoln and, when Lincoln called for volunteers to put down the Southern rebellion, he felt compelled to be among them.

In 1855, Ballou married Sarah Hart Shumway, a young lady of 19, described as intelligent and “proper.” Their first child, Edgar Fowler Ballou, was born in August 1856 and, two years later, a second son, William Bowen Ballou, would follow. Sullivan and Sarah’s marriage was, by all accounts, a very happy one, and Sullivan’s career was extremely promising. By the time the Civil War broke out, he was 32, had a prosperous law practice, and was already a former speaker of the Rhode Island House of Representatives. But, Sullivan Ballou was also an ardent supporter of Abraham Lincoln and, when Lincoln called for volunteers to put down the Southern rebellion, he felt compelled to be among them.

However, while Ballou had no trepidation in serving, he did feel pain at being separated from Sarah and his two little boys. And, perhaps more so, he also worried about what would happen to them should be killed in battle. He knew that his sons would become orphans, as he had been, and this prospect caused him great concern. But, he knew that Sarah was a very capable and loving mother, and that she would see the boys through. However, he also worried about her and obviously agonized over the prospect of her becoming a widow at 25. And it was all these emotions that he poured out to her when he wrote his letter on that July night in 1861.

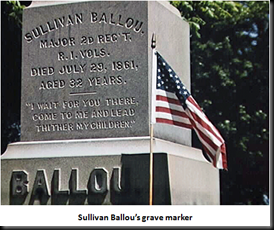

As anyone who knows of the letter is probably aware, Ballou would die of wounds received at Bull Run one week after he wrote to Sarah. He was buried in the yard of nearby Sudley Church and, after Confederate forces reoccupied the area, several ghoulish soldiers from Georgia exhumed, decapitated, and desecrated his corpse. His body was never recovered, but charred ash and bone believed to be his remains were found and reburied with full military honors in Swan Point Cemetery, Providence, Rhode Island, on March 31, 1862.

As anyone who knows of the letter is probably aware, Ballou would die of wounds received at Bull Run one week after he wrote to Sarah. He was buried in the yard of nearby Sudley Church and, after Confederate forces reoccupied the area, several ghoulish soldiers from Georgia exhumed, decapitated, and desecrated his corpse. His body was never recovered, but charred ash and bone believed to be his remains were found and reburied with full military honors in Swan Point Cemetery, Providence, Rhode Island, on March 31, 1862.

However, while those who know about the letter are aware of Ballou’s death at Bull Run, many may not realize that his letter was never mailed. Rather, he left it among his personal effects, knowing that, if he were killed in battle, Sarah would find the letter among his belongings when they were eventually shipped home. And, according to the story, that is how she came to find it.

Sarah would never remarry, raising her two sons, and making do on the $29 per month she received from a government pension along with money she earned from teaching piano lessons. In 1875, she became the secretary of the Providence School Committee, where she served until 1899. She eventually moved to East Orange, New Jersey to be near her grown son, Willie. She died in 1917 at the age of 81 and, on a pleasant spring day with a light rain falling, Sarah was laid to rest in Swan Point Cemetery next to her husband. The original copy of the letter from Sullivan has never been found and one story states that is because Sarah asked her sons to place it in her hands and bury it with her. I cannot confirm the truth of that story, but, if it isn’t true, it probably should be.

Sarah would never remarry, raising her two sons, and making do on the $29 per month she received from a government pension along with money she earned from teaching piano lessons. In 1875, she became the secretary of the Providence School Committee, where she served until 1899. She eventually moved to East Orange, New Jersey to be near her grown son, Willie. She died in 1917 at the age of 81 and, on a pleasant spring day with a light rain falling, Sarah was laid to rest in Swan Point Cemetery next to her husband. The original copy of the letter from Sullivan has never been found and one story states that is because Sarah asked her sons to place it in her hands and bury it with her. I cannot confirm the truth of that story, but, if it isn’t true, it probably should be.

In his own way, Sullivan Ballou would eloquently express what thousands of men probably felt both that night in July 1861 and in the many nights that would follow over the next four years of the war: Dedication to country and cause, combined with intense devotion to home and family. That’s why, for me, Sullivan Ballou and his letter to Sarah have come to symbolize the generation that fought this war. His passionate belief in the cause of preserving the Union, of securing what Lincoln would call the “last, best hope” of all humanity, rings forth with true passion. But, at the same time, his love for Sarah and his intense devotion to her is also equaling overpowering.

In that sense, I must admit that Sullivan’s letter also goes far beyond either its symbolism as being emblematic of his generation or of being merely “romantic.” It is a passionate expression of a love felt so deeply, that it will somehow survive death and truly be eternal. In that sense, it is the living example of the love all of us probably seek both to give and to receive during our lifetime.

I think it is time for me to stop talking and allow Sullivan Ballou to speak for himself. For those who have never heard the letter, as well as those who might want to hear it again, here is Sullivan’s remarkable, beautiful, and, yes, tragic letter to his beloved Sarah, both in audio and in text, as it was presented by Ken Burns.

July 14, 1861

Camp Clark, Washington

Dear Sarah:

The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days - perhaps tomorrow. And lest I should not be able to write you again I feel impelled to write a few lines that may fall under your eye when I am no more.

I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how American Civilization now leans upon the triumph of the government and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution. And I am willing - perfectly willing - to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt.

Sarah, my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me with mighty cables that nothing but omnipotence can break; and yet my love of Country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly with all those chains to the battlefield. The memory of all the blissful moments I have enjoyed with you come crowding over me, and I feel most deeply grateful to God and you, that I have enjoyed them for so long. And how hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes and future years, when, God willing, we might still have lived and loved together, and see our boys grown up to honorable manhood around us.

If I do not return, my dear Sarah, never forget how much I loved you, nor that when my last breath escapes me on the battle field, it will whisper your name...

Forgive my many faults, and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless, how foolish I have sometimes been!...

But, 0 Sarah, if the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen around those they love, I shall always be with you, in the brightest day and in the darkest night... always, always. And when the soft breeze fans your cheek, it shall be my breath, or the cool air your throbbing temple, it shall be my spirit passing by.

Sarah do not mourn me dead; think I am gone and wait for me, for we shall meet again...