On November 20, 1861, a tall young man with dark brown hair and a complexion tanned by many hours working in the sun walked into the post office in Webb’s Mill, Virginia to enlist in the Ritchie County company of the 3rd West Virginia Infantry Regiment. He was only 18 years of age and, when he had heard that a recruiter would be enlisting men from the county in the service of the Union, he had walked to Webb’s Mill from his family farm in neighboring Calhoun County to sign up. Ritchie and Calhoun Counties were two of the northwestern counties of Virginia that had voted overwhelmingly for Lincoln, opposed Virginia’s secession, and remained steadfastly loyal to the United States. The young man’s name was Samuel Albert Snider, and he was my great-great-great Uncle.

Samuel Snider was born in 1843, the fourth son of David and Mary Snider, in Allegheny County, Maryland. The Snider family left Maryland in 1858 for what was then the western counties of Virginia, eventually settling in Nobe. His enlistment records show him as six-foot, one-inch tall, much taller than the average height for a Union soldier, which was only five-foot, seven inches. His records also state that he had dark hair and complexion, hazel eyes, and giving his occupation as farmer. Although his older brother, John, had enlisted in the 11th West Virginia Infantry Regiment a few days earlier, he was still waiting to be mustered into service when Samuel and his fellow enlistees took off over the Stauton Pike for Camp Elkwater in Randolph County.

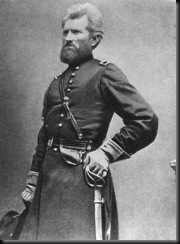

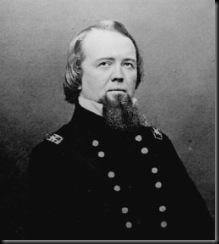

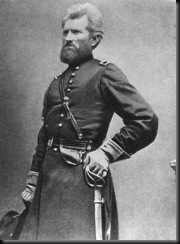

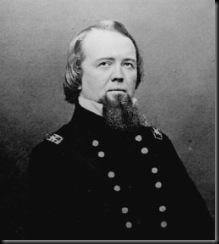

Camp Elkwater was located in the Tygart Valley about five miles north of Huttonville, Virginia, near what is today the small town of Valley Bend, West Virginia, on U.S. Highway 250/291. The regiment was in winter camp when Samuel and his company arrived to begin training. The commander of Company K was Captain Hall, while the regiment was commanded by Colonel Hewes. The 3rd West Virginia was aligned in a brigade led by the, sometimes, charismatic and, often, excitable General Robert Milroy. Samuel was formally mustered-in to the regiment on November 26, 1861.

Camp Elkwater was located in the Tygart Valley about five miles north of Huttonville, Virginia, near what is today the small town of Valley Bend, West Virginia, on U.S. Highway 250/291. The regiment was in winter camp when Samuel and his company arrived to begin training. The commander of Company K was Captain Hall, while the regiment was commanded by Colonel Hewes. The 3rd West Virginia was aligned in a brigade led by the, sometimes, charismatic and, often, excitable General Robert Milroy. Samuel was formally mustered-in to the regiment on November 26, 1861.

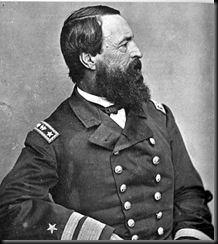

At that time, the 3rd West Virginia was assigned to the District of West Virginia under the overall command of the famous western explorer, General John C. Fremont. The area underwent several reorganizations and, in April 1862, as the regiment prepared to break winter camp, it was re-designated the Department of the Mountains with the brigade renamed as Milroy's Independent Brigade. As this reorganization was underway, Fremont received orders to take part in a combined operation against Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley.

At that time, the 3rd West Virginia was assigned to the District of West Virginia under the overall command of the famous western explorer, General John C. Fremont. The area underwent several reorganizations and, in April 1862, as the regiment prepared to break winter camp, it was re-designated the Department of the Mountains with the brigade renamed as Milroy's Independent Brigade. As this reorganization was underway, Fremont received orders to take part in a combined operation against Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley.

In the Shenandoah, the Confederate Army of the Valley, led by the famous Stonewall Jackson, was moving northeast down the valley toward the Potomac River and the backdoor to Washington. His intent was to endanger the capital, thereby drawing Federal forces nearby into battle, thus preventing them from moving south to help General McClellan who was slowly marching up the James Peninsula toward Richmond. The Federal concept for dealing with this threat was to take the offensive and attack Jackson's army from both ends of the valley. To that end, a Union army under the command of General Nathanial Banks had been sluggishly pushing up the valley from the north end near Winchester. To help Banks, Fremont now ordered Milroy and General Schenck to lead their brigades as a vanguard force into the southern end of the Shenandoah and seize the key town of Stauton, which sat astride the southern terminus of the Valley Pike. Fremont would then follow with the bulk of the Federal forces.

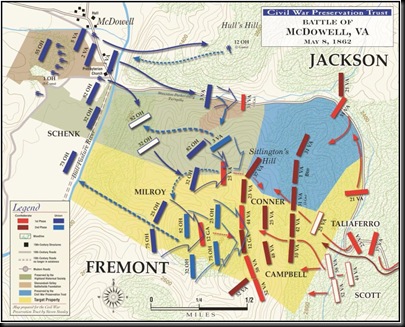

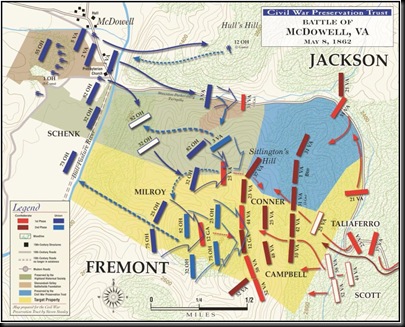

On April 5, 1862, in the midst of a spring snowstorm, Milroy's brigade, numbering some 3,500 men, moved out of Camp Elkwater and marched southeast across the mountains via the Stauton Pike to Monterey, Virginia. There, on April 12, 1862, Samuel saw his first action when a small Confederate detachment tried to dislodge Milroy's forces from the town. The Confederate attack was quickly turned away and the attackers retreated to join a larger force of 2,800 men under General Edward Johnson. The 3rd West Virginia remained in Monterey until April 30, when they moved nine miles forward to the town of McDowell, Virginia. There, they and the rest of the brigade would await reinforcements from Fremont's army.

On May 7, what was expected to be the first of these reinforcements under General Schenck arrived, bringing the Federal strength in McDowell to just under 6,000 men. Schenck, being senior to Milroy, assumed command and, that being done, received the disturbing news that Stonewall Jackson and the entire Army of the Valley, had arrived in Stauton on May 5. It seems that Jackson, having heard from General Johnson that a sizable Union force was moving into the Shenandoah, had decided to quickly shift his direction of attack from the northern end of the valley toward this new threat from the west. As a result, within hours, Schenck and Milroy received reports from scouts that General Johnson's forces were already taking positions directly across from McDowell on a spur of Bull Pasture Mountain called Stilington's Hill. Worse, they discovered that they were already outnumbered, with Jackson's rapidly arriving forces bringing Confederate strength to over 10,000 men. In addition, not even the terrain was favorable since the Southern lines were staring down at McDowell from a height some 500 feet above the smaller Union force.

As evening fell, Milroy rapidly deployed his artillery across the valley floor on a ridge that ran parallel to Stilington's Hill about 500 yards west of the Confederate positions. On the morning of May 8, the artillery, their tubes elevated by mounting the trails of the guns in trenches, began to fire gamely at the Confederates on the opposite hill. As the guns opened fire, scouts arrived to tell the two Federal commanders that Confederate artillery was nearby and would arrive soon to add to the Southern forces' firepower. With this news, Schenck and Milroy realized that: retreat was their only option. However, to attempt retreat in the face of such superior numbers could be disastrous. Therefore, they elected to give the enemy one hard punch, stun him before his artillery arrived and, thus, hold Jackson off till nightfall, when Union forces could safely retreat.

At about 4:30 p.m., 2,000 Federal troops, including Samuel Snider and the 3rd West Virginia, crossed the Bull Pasture River on a bridge concealed from Confederate view and charged up the steep slopes of Stilington's Hill. When the attack came, General Jackson was at the rear bringing up more men and General Johnson was in immediate command of Confederate forces on the hill. The initial Union thrust almost undid Johnson's men by nearly overrunning their right flank. Jackson, hearing the sound of gunfire, began to rush additional infantry forward as the Federals struck Johnson's most vulnerable point-the center. Here, a Confederate wedge pointed toward the attacking enemy, exposing the Southern defenders to fire from their front and flanks. The imperiled sector was manned by the 12th Georgia, the only non-Virginia unit in Jackson's army. When ordered to pull back, the Georgian's refused. Instead, they stood up to better fire down on the hillside. Unfortunately, this silhouetted them against the sky, making them better targets, and they took heavy losses.

At about 4:30 p.m., 2,000 Federal troops, including Samuel Snider and the 3rd West Virginia, crossed the Bull Pasture River on a bridge concealed from Confederate view and charged up the steep slopes of Stilington's Hill. When the attack came, General Jackson was at the rear bringing up more men and General Johnson was in immediate command of Confederate forces on the hill. The initial Union thrust almost undid Johnson's men by nearly overrunning their right flank. Jackson, hearing the sound of gunfire, began to rush additional infantry forward as the Federals struck Johnson's most vulnerable point-the center. Here, a Confederate wedge pointed toward the attacking enemy, exposing the Southern defenders to fire from their front and flanks. The imperiled sector was manned by the 12th Georgia, the only non-Virginia unit in Jackson's army. When ordered to pull back, the Georgian's refused. Instead, they stood up to better fire down on the hillside. Unfortunately, this silhouetted them against the sky, making them better targets, and they took heavy losses.

Samuel and the 3rd West Virginia, meanwhile, were ordered to attack the Confederate right along the turnpike road that led east out of McDowell. Ironically, the Confederate unit defending the road was the 31st Virginia, whose Company C had been recruited from the Clarksburg, West Virginia area just as had Companies B, F, and G of the 3rd West Virginia. The two lines closed to within 50 yards of one another and, as men from Clarksburg recognized former friends, they exchanged salutes and "Hellos" along with murderous rifle fire. About this time, as darkness fell, Confederate reinforcements arrived in the form of Jackson's 2nd Brigade and Milroy's forces retired back down the hill and across the river.

Samuel and the 3rd West Virginia, meanwhile, were ordered to attack the Confederate right along the turnpike road that led east out of McDowell. Ironically, the Confederate unit defending the road was the 31st Virginia, whose Company C had been recruited from the Clarksburg, West Virginia area just as had Companies B, F, and G of the 3rd West Virginia. The two lines closed to within 50 yards of one another and, as men from Clarksburg recognized former friends, they exchanged salutes and "Hellos" along with murderous rifle fire. About this time, as darkness fell, Confederate reinforcements arrived in the form of Jackson's 2nd Brigade and Milroy's forces retired back down the hill and across the river.

In the aftermath of the brief five-hour fight, Jackson found he had lost 498 men while, across the river, Milroy counted 256 casualties. Jackson fully intended to resume the battle the next morning, however, when the sun came up, he discovered Milroy and Schenck were gone, having skillfully departed during the night. His scouts told him that the West Virginians were retreating rapidly northeast towards Franklin so Jackson set off in pursuit. But, Milroy was not only too quick for him, the West Virginians complicated matters for Stonewall by setting fire to the woods along the road, causing the Rebels to dance on hot embers as they groped their way through eye-stinging clouds of smoke. With regretful admiration, Jackson called a halt near Franklin and began a return to Stauton, where he would go back down the Shenandoah on the offensive against Banks and the main body of Federal forces in the valley.

On May 11, Samuel and his regiment were encamped at Franklin, on the west side of the Shenandoah Mountains. While Milroy's men and, indeed, all of Fremont's army, remained in camp outside the valley, Jackson's Army of the Valley rampaged down the Shenandoah, repeatedly defeating General Banks' ill-led forces. In late May, Jackson was at the far northern end of the valley and President Lincoln ordered Fremont to move his army into the valley to Harrisonburg so as to block Jackson from leaving the Shenandoah. Instead, Fremont ordered his army northeast to Moorefield. On May 27, Lincoln, upon hearing that Fremont was still not in the valley, angrily telegraphed the former explorer and presidential candidate demanding an explanation. Fremont's reply was to tell the President that he would enter the Shenandoah at Strasburg and block the Valley Pike by May 31. However, at 8:00 p.m. on that date, following a slow march, Milroy's brigade, again the vanguard, was still 15 miles west of Strasburg and, unknown to them, Jackson was already south of Strasburg, heading up the valley to safety.

So, what was to have been a trap for Jackson, now turned into a mad chase up the Shenandoah Valley. On June 8, Fremont caught up with Jackson at Cross Keys. The "battle" of Cross Keys turned out to be nothing more than a nasty skirmish. Fremont only committed part of his force and, when it was repulsed, he held the rest, including Samuel's regiment, back from battle. The next day, Jackson engaged another Union army at Port Republic while Fremont watched from across the Shenandoah River. Jackson was again victorious and, then, he quietly left the valley. For Jackson, the work he had been assigned had been finished. He had kept Banks from going to augment McClellan's Army of the Potomac near Richmond and, with that assignment complete, he now moved rapidly to the east to join General Johnston's army in driving McClellan back.

In the ensuing weeks, defeats on the battlefield and political shakeups in the Union Army would affect Samuel Snider and the 3rd West Virginia. First, as a result of his poor showing in the Shenandoah, Fremont was sacked by Lincoln. Then, McClellan, who had managed to lose to inferior numbers repeatedly in the Seven Days' Battles near Richmond and now sat with his huge army at Harrison's Landing on the James River, was relieved from his position as General-in-Chief of the U.S. Army. While McClellan would remain in command of the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln replaced him as head of the army with General Henry Halleck. Halleck, in turn, decided to create a new Union army, the Army of Virginia, under the command of General John Pope, who promised Lincoln great victories.

As a part of the creation of the Army of Virginia, Milroy's Independent Brigade was moved east from the Shenandoah to northern Virginia. Here, the men of the 3rd West Virginia were to remain with Milroy's brigade and were joined in it by the 2nd and 5th West Virginia Infantry, the 82nd Ohio Infantry, 1st West Virginia Cavalry, 12th Ohio Independent Artillery Battery and Rigby's Indiana Artillery Battery. The brigade as a whole was placed in I Corp of the Army of Virginia under General Franz Sigel. Sigel was a German immigrant who's sole military experience carne as an officer during the German Revolution. As such, he was a poor choice as a corps commander, but his influence with the German immigrant community was considered important.

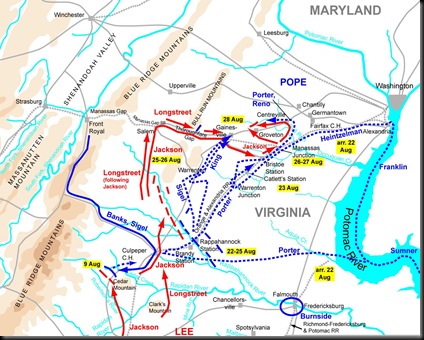

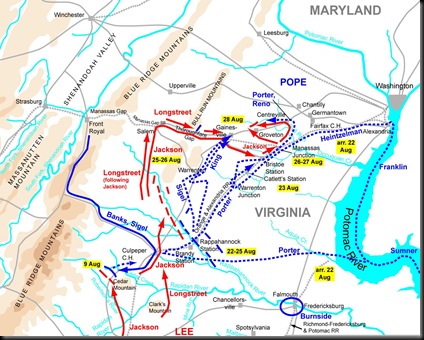

By late July 1862, Pope had placed his army on the north side of the Rappahannock River facing General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. With much bombast and bragging, Pope had moved out and engaged Jackson at Cedar Mountain. In this battle, which saw no action by any of Milroy's brigade, Pope had lost decisively and, as a result, he now became timid and, in fact, seemed to become completely confused. Pope placed his army in defensive positions along the Rappahannock, hoping to draw Lee away from McClellan so that McClellan could extract his army from the James Peninsula and unite with Pope. But, McClellan was slow as always and, frankly, was secretly hoping something would happen to embarrass Pope. General Lee obliged him.

Lee decided to strike north and move the war away from Richmond, possibly even into the northern states themselves. So, he ordered Stonewall Jackson and General James Longstreet to march around Pope's right flank and then turn through Thoroughfare Gap to get between Pope's army and Washington. Jackson moved out first in the early morning darkness of August 25 and headed towards White Plains. By nightfall, his army was rapidly approaching their initial objective while General Longstreet prepared to move the next afternoon.  Pope received information that Jackson was on the move late on August 25, but seemed completely baffled about exactly what to do. He proceeded to issue a series of confusing, contradictory orders that sent various parts of the army in different directions with no apparent strategy involved. A classic example of how totally confused Pope became occurred that day and involved Sigel's corps, Milroy's brigade, and, thus, Samuel Snider. At 11:25 a.m., Pope ordered Sigel to withdraw from his position along the Rappahannock at Sulpher Springs and Waterloo Bridge, and march southeast to Fayettville. However, at noon, Sigel counted 12 Confederate regiments and six batteries of artillery opposite him and informed Pope that withdrawal was impossible under these conditions. By the time Sigel's message reached Pope, the commander of the Army of Virginia was aware that Jackson was moving somewhere to his right. Therefore, he ordered Sigel to hold his "position at Waterloo Bridge under all circumstances and to meet the enemy if he should try to force the passage of the river."

Pope received information that Jackson was on the move late on August 25, but seemed completely baffled about exactly what to do. He proceeded to issue a series of confusing, contradictory orders that sent various parts of the army in different directions with no apparent strategy involved. A classic example of how totally confused Pope became occurred that day and involved Sigel's corps, Milroy's brigade, and, thus, Samuel Snider. At 11:25 a.m., Pope ordered Sigel to withdraw from his position along the Rappahannock at Sulpher Springs and Waterloo Bridge, and march southeast to Fayettville. However, at noon, Sigel counted 12 Confederate regiments and six batteries of artillery opposite him and informed Pope that withdrawal was impossible under these conditions. By the time Sigel's message reached Pope, the commander of the Army of Virginia was aware that Jackson was moving somewhere to his right. Therefore, he ordered Sigel to hold his "position at Waterloo Bridge under all circumstances and to meet the enemy if he should try to force the passage of the river."

By mid-afternoon, Sigel had deployed his corps to defend the river crossing and was even more convinced that, indeed, the Rebels were going to attack across the river. Therefore, he sent requests for help to Generals Reno and Banks, whom he presumed to be on his left, but was astonished to learn that they had marched under Pope's orders far to the south. To make matters worse, Sigel soon discovered that the troops on his right flank had also left the area under orders from General Pope. Now, having discovered he was defending the river crossing with no support on his right or left, Sigel received new orders from Pope. These orders called for him to, again, withdraw from the bridge and march eight miles southeast to Fayetteville. He sent for clarification not believing that Pope really expected him to withdraw in the face of the enemy with no support, but none was received. So, he decided to withdraw his corps after dark, with the exception of Milroy's brigade. Milroy was ordered to remain behind, bum the Waterloo Bridge to prevent a Confederate attack, and then catch up with the rest of the corps.

As darkness fell, Sigel moved off with Milroy guarding the rear. But, before Sigel got very far, he received yet another change in orders from General Pope. This dispatch told him to turn 90 degrees to the left and march northwest to Warrenton. This was done and, hours later as the corps reached the outskirts of Warrenton, Milroy's brigade caught up with the corps and Milroy reported the successful destruction of the Waterloo Bridge.

Within minutes of this, however, a new dispatch arrived from Pope. He now had changed his mind and ordered Sigel to turn around, march back to the Waterloo Bridge and "force a passage of the bridge at daylight." To attack across a bridge he had just burned in accordance with Pope's orders was obviously impossible. Moreover, the men were exhausted from a day of marching all over the Virginia countryside. Sigel rode directly to Pope's headquarters to protest these latest in a series of imbecilic orders. A violent argument ensued in which Sigel asked to be relieved. Cooler heads prevailed, however, and Sigel returned to Warrenton.

Finally, everything ground to halt and, essentially, despite all the movement by Union forces, no one had really gone anywhere. Then, on the night of August 27, Jackson's forces struck the Union supply depot at Manassas Junction. Pope now realized that Jackson was in his rear between him and Washington. To his credit, however, he realized that since Longstreet was still moving towards Thoroughfare Gap and, thus, was separated from Jackson, an opportunity existed to destroy Stonewall Jackson before Longstreet arrived. He quickly ordered the army to move east towards Manassas Junction. Unfortunately, Jackson was too quick for Pope. On August 28, Jackson proceeded to double back and place himself northeast of Manassas Junction, just north of the Warrenton Pike near the village of Groveton. Worse, Pope lost track of Jackson and, when he did find him, he thought he was attacking a retreating Confederate force. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Jackson had placed his men in strong defensive positions in an abandoned railroad cut amid heavy trees and was more than anxious to have a go at John Pope.

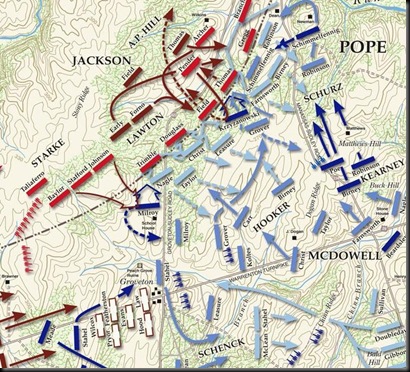

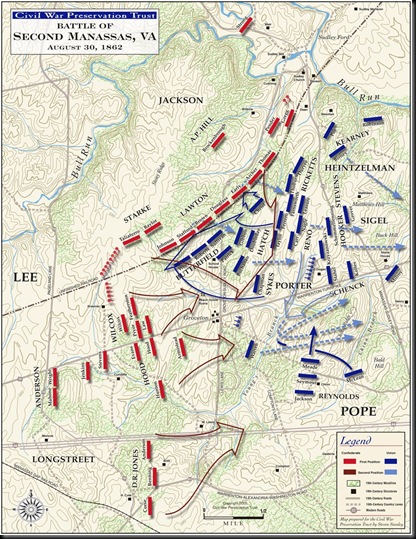

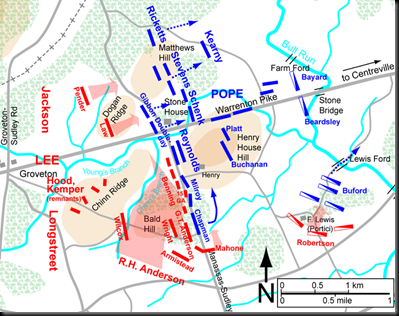

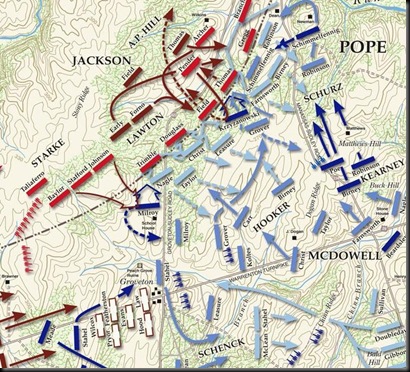

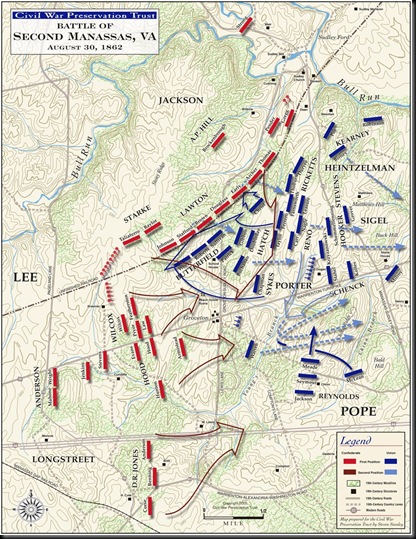

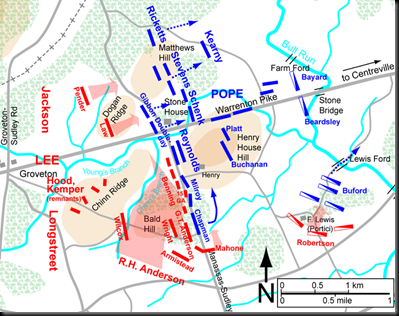

Dawn of August 29, 1862, found Samuel Snider and his regiment encamped on Henry House Hill, the site of Jackson's famous "Stonewall" stand at the Battle of First Manassas the previous summer. At 3:00 a.m., General Sigel received orders to move I Corp forward, find Jackson's position, and engage him. Sigel and his staff rode out just before first light to reconnoiter the terrain and, as a result, did indeed find Stonewall Jackson and his men. However, given his lack of true military experience, Sigel was unable to discern the precise positions Jackson was occupying and his plan of attack reflected that uncertainty. Rather than concentrating his 9,000 men at a single spot, Sigel chose to attack across a two-mile wide front. He ordered General Schurz to move his division northwest toward what was the far left of Jackson's line, while General Schenck's two brigades moved along the Warrenton Pike against Jackson's right. Milroy's brigade, meanwhile, was told to move forward on Schurz's left toward what was, unknown to Sigel, the very center of Jackson's forces.

Upon receiving these orders, the energetic Milroy yelled to his brigade, "Fall in boys; we're going to whip them before breakfast!" After a few opening shots from Federal batteries located on Chinn Ridge, south of the Warrenton Pike - shots that did nothing but alert the Confederates to Sigel's advance - Samuel and the rest of Milroy's brigade along with all of I Corp started forward. Within an hour, Schurz's division found Jackson's skirmishers on the right and drove headlong into the woods and across the open fields in front of the railroad cut. Initially, they met success, driving some South Carolina regiments back. But, soon, the Confederates rallied and pushed Schurz's men back.

Upon receiving these orders, the energetic Milroy yelled to his brigade, "Fall in boys; we're going to whip them before breakfast!" After a few opening shots from Federal batteries located on Chinn Ridge, south of the Warrenton Pike - shots that did nothing but alert the Confederates to Sigel's advance - Samuel and the rest of Milroy's brigade along with all of I Corp started forward. Within an hour, Schurz's division found Jackson's skirmishers on the right and drove headlong into the woods and across the open fields in front of the railroad cut. Initially, they met success, driving some South Carolina regiments back. But, soon, the Confederates rallied and pushed Schurz's men back.

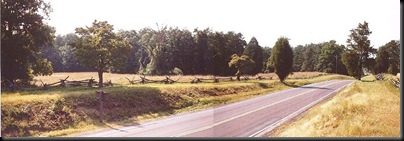

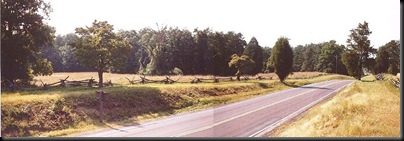

Meanwhile, Milroy moved north of the Warrenton Pike toward Groveton Woods, a small grove of timber just north of the intersection of the Warrenton Pike and Groveton-Sudley Road. Here, the 3rd West Virginia found skirmishers from Starke's Louisiana brigade. They quickly drove them out and back across the road. As Milroy formed his men in the Groveton Woods, they came under intense artillery fire. To counter this threat, Milroy combined his guns with artillery from Schenck's division to form a 21-gun battery just east of the woods. The Federal gunners opened fire but were unable to silence the Southern guns. So, Samuel and his comrades huddled in the woods under a rain of shellfire awaiting the inevitable order to advance.

The situation in the Groveton Woods seemed to serve to agitate General Milroy's mercurial nature. Hearing the gunfire from Schurz's attack against Jackson's left, he somehow decided that he must aid Schurz, although he had no idea what Schurz's situation was. Therefore, he ordered the 5th West Virginia and 82nd Ohio to march 600 yards across Jackson's front to attack in support of Schurz while the 2nd and 3rd West Virginia attacked the center of the Confederate line-alone. The fact that he had no supporting troops didn't seem to bother Milroy in the least. "These circumstances should have suggested caution, to say the least," remembered one of Milroy's staff officers, "but that was a virtue not known to Milroy."

The situation in the Groveton Woods seemed to serve to agitate General Milroy's mercurial nature. Hearing the gunfire from Schurz's attack against Jackson's left, he somehow decided that he must aid Schurz, although he had no idea what Schurz's situation was. Therefore, he ordered the 5th West Virginia and 82nd Ohio to march 600 yards across Jackson's front to attack in support of Schurz while the 2nd and 3rd West Virginia attacked the center of the Confederate line-alone. The fact that he had no supporting troops didn't seem to bother Milroy in the least. "These circumstances should have suggested caution, to say the least," remembered one of Milroy's staff officers, "but that was a virtue not known to Milroy."

The attack did not get off to a good start. The 82nd Ohio and 5th West Virginia were misdirected and, rather than moving to the right-front to find Schurz's flank, they ended up advancing directly at the unfinished railroad cut and into Jackson's guns. They recoiled under the intense fire from the cut but did manage to briefly carry the entrenchment. However, a quick counterattack drove them scurrying back down the hill towards the woods. Milroy now ordered the 2nd West Virginia to go to the two regiments' assistance. The 2nd went in but the intense fire drove them quickly back to the woods. In a few minutes, the 2nd had lost 20 killed and 100 wounded and missing.

Milroy then turned to the 3rd West Virginia's commander, Major Theodore Lang, saying "Major Lang, now is the opportunity to distinguish yourself! I want you to charge the railroad embankment...and see what is behind it." Major Lang then arranged the regiment in a line of battle extending perhaps 150 yards and they moved out of the Groveton Woods, across the road, and towards the railroad cut. The ground in front of them was open, broken by a small creek in the center, and heavy trees on the right. The first 200 yards was flat but the final 100 yards rose quickly some 60-80 feet to the edge of the railroad cut. At first, only scattered rifle fire met the 3rd's advance. But, when they started up the slope and had reached to within 50 yards of the cut, Starke's Louisianans leaped up from the cover of the trench and poured a withering fire into the West Virginians. The regiment stopped and managed to fire two volleys before it finally broke and, according to Major Lang, "beat a hasty retreat" back to the Groveton Woods. As other regiments from General Heitzelman's corps arrived to renew the attack, Milroy's brigade gathered east of the Groveton Woods, a bloodied and disorganized shambles.

As the day wore on, more Federal troops dashed themselves unsuccessfully against the railroad cut. Milroy had managed to get the brigade back into relative order and spent the afternoon observing the Union attack from the Groveton Woods. At about 4:00 p.m., he observed the seemingly successful attack by troops under General Nagle with interest and, becoming excited again, decided to send in the 3rd West Virginia in an uncoordinated supporting attack. The 3rd moved out quickly but Milroy remembered, "before I got near across the meadow I noticed heavy masses of Rebels in front and as far down the railroad as I could see ... " The normally combative Milroy saw the folly of attacking this force with one little regiment. He yelled for the 3rd to fall back, but the loud din of battle obscured his voice and the 3rd pressed on. However, when the regiment got to within 100 yards of the Confederates, a sheet of flaming rifle fire convinced them to fall back. They turned and ran for the cover of the Groveton Woods.

As the day wore on, more Federal troops dashed themselves unsuccessfully against the railroad cut. Milroy had managed to get the brigade back into relative order and spent the afternoon observing the Union attack from the Groveton Woods. At about 4:00 p.m., he observed the seemingly successful attack by troops under General Nagle with interest and, becoming excited again, decided to send in the 3rd West Virginia in an uncoordinated supporting attack. The 3rd moved out quickly but Milroy remembered, "before I got near across the meadow I noticed heavy masses of Rebels in front and as far down the railroad as I could see ... " The normally combative Milroy saw the folly of attacking this force with one little regiment. He yelled for the 3rd to fall back, but the loud din of battle obscured his voice and the 3rd pressed on. However, when the regiment got to within 100 yards of the Confederates, a sheet of flaming rifle fire convinced them to fall back. They turned and ran for the cover of the Groveton Woods.

As the day's fighting drew to a close, Samuel Snider and his regiment withdrew to the area just north of the Stone House at the junction of Sudley Road and the Warrenton Pike. As the regiment licked its wounds that night, General Pope met with his staff inside the Stone House to devise the next day's strategy. What should have been most disturbing to Pope was the news that General Longstreet and his army of 25,000 men had passed through Thoroughfare Gap last night and arrived on the field late that afternoon. However, John Pope's ability to delude himself made Longstreet's presence a mere nuisance.

Pope believed all along that he would batter Jackson long before Longstreet got there. As a result, he had only sent a small delaying force to Thoroughfare Gap, which Longstreet had pushed aside after a brief but intense firefight. Since Longstreet now on the field, Pope completed the delusion by convincing himself that Jackson had indeed been badly beaten by the day's repeated Union assaults. Therefore, his theory continued, Longstreet would deploy west of Jackson to cover his retreat. Pope's plan called for more massive assaults on Jackson beginning at dawn on August 30. Unfortunately, the Confederates were not to cooperate with Pope's plan.

Jackson's men were indeed tired from the long day of fighting, but their casualties were relatively light. Also, unknown to Pope, General Lee had arrived with Longstreet and had assumed direct command. Rather than deploying Longstreet to the west, behind Jackson, Lee sent Longstreet's corps to the right, extending his line far to the south of the Warrenton Pike. As a result of this move and Pope shifting more men to attack north of the pike, Longstreet would find his 25,000 men opposed by one Federal division of less than 6,500 men.

On the morning of August 30, Samuel and the remainder of Milroy's brigade remained in reserve, posted in the area around the Stone House and Henry House Hill, as Pope unleashed a series of assaults against Jackson. These attacks were again turned back over and over. But, Pope merely deluded himself even more. By early afternoon, reports of Confederate troop movements convinced Pope that Jackson was indeed retreating. In fact, these reports were actually based upon the deployment of even more Confederate troops south of the Warrenton Pike. As a result of his fantasy, Pope ordered fresh attacks on Jackson’s corps by Reynolds' division, which was the only unit opposite Longstreet.

On the morning of August 30, Samuel and the remainder of Milroy's brigade remained in reserve, posted in the area around the Stone House and Henry House Hill, as Pope unleashed a series of assaults against Jackson. These attacks were again turned back over and over. But, Pope merely deluded himself even more. By early afternoon, reports of Confederate troop movements convinced Pope that Jackson was indeed retreating. In fact, these reports were actually based upon the deployment of even more Confederate troops south of the Warrenton Pike. As a result of his fantasy, Pope ordered fresh attacks on Jackson’s corps by Reynolds' division, which was the only unit opposite Longstreet.

Pope ordered General Reynolds to shift his division northward and attack Jackson immediately. But, while Reynolds had not ascertained the exact size or significance of the force to his front, he had received numerous reports from pickets of movements in the trees and hills beyond them. One of the most competent professional soldiers in the army, Reynolds relayed his concerns to Pope, adding that they might indicate a Confederate attack on the exposed Union left flank. Pope quickly dismissed such a suggestion in light of what he was sure was an impending breakthrough against Jackson. Reynolds, therefore, requested and received permission from Pope to leave two brigades of Ohioans south of the pike, on Chinn Ridge. Longstreet now only faced 2,500 Federal troops.

Late in the afternoon Lee unleashed Longstreet’s corps. The Confederates quickly overran the 5th New York, which was acting as a skirmish line for the Ohio brigades, killing or wounding 500 of 650 New Yorkers in less than 10 minutes. Longstreet’s men paused briefly and then moved up Chinn Ridge. Within minutes, the Ohio boys were hanging on by their fingernails, giving ground slowly. Word of the predicament on the Union left reached Pope and he ordered Sigel to move to aid the rapidly collapsing flank. Milroy's brigade was the last to march.

Late in the afternoon Lee unleashed Longstreet’s corps. The Confederates quickly overran the 5th New York, which was acting as a skirmish line for the Ohio brigades, killing or wounding 500 of 650 New Yorkers in less than 10 minutes. Longstreet’s men paused briefly and then moved up Chinn Ridge. Within minutes, the Ohio boys were hanging on by their fingernails, giving ground slowly. Word of the predicament on the Union left reached Pope and he ordered Sigel to move to aid the rapidly collapsing flank. Milroy's brigade was the last to march.

The weight of Longstreet's attack was too much for Sigel's men to stop. The entire Army of Virginia was now threatened. Pope, realizing this, ordered the army to fall back to positions east of Bull Run Creek. Unfortunately, there was only one bridge, the Stone Bridge, across the creek. Therefore, it was crucial that the route to the bridge be kept open and that the retreating army’s flank remain secure. The only place left to stop the surging Confederates from cutting off the entire army, flanking it, and destroying it was Henry House Hill.

Pope ordered Milroy to stop his movement toward Chinn Ridge and proceed to form a line just west of Henry House Hill on the Sudley Road. There, Milroy was reinforced by Reynolds' Pennsylvania division and a brigade of General Sykes' Regulars. The roadbed at the base of the hill was sunken three to five feet, creating a natural bulwark. As Samuel and the 3rd West Virginia moved into place between Reynolds and Sykes' men, Sykes' other two brigades and his artillery took positions behind Milroy's line, on the west slope of Henry House Hill. It was now 6:00 p.m. and, as the last of the fleeing Union troops from Chinn Ridge dashed past the Henry House Hill defenders, Southern artillery rounds began to fall on the slopes of the hill.

Pope ordered Milroy to stop his movement toward Chinn Ridge and proceed to form a line just west of Henry House Hill on the Sudley Road. There, Milroy was reinforced by Reynolds' Pennsylvania division and a brigade of General Sykes' Regulars. The roadbed at the base of the hill was sunken three to five feet, creating a natural bulwark. As Samuel and the 3rd West Virginia moved into place between Reynolds and Sykes' men, Sykes' other two brigades and his artillery took positions behind Milroy's line, on the west slope of Henry House Hill. It was now 6:00 p.m. and, as the last of the fleeing Union troops from Chinn Ridge dashed past the Henry House Hill defenders, Southern artillery rounds began to fall on the slopes of the hill.

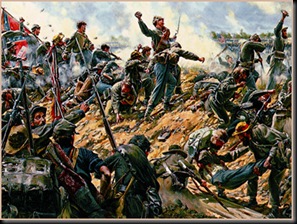

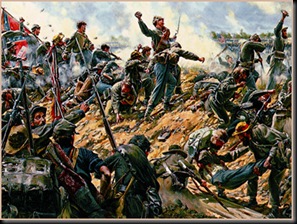

Evening was coming on and thunderstorms began to build in the west. As the sun set in what eyewitnesses remember as a sea of fiery red clouds, 3,000 Georgians emerged from the trees to Samuel’s front in a line almost a half-mile long. They surged out the forest screaming the Rebel yell and sprinted towards the Union troops standing in the Sudley Road. The West Virginians opened fire at 100 yards and the Confederates staggered, broke, and fell back into the woods. Within minutes, however, they came on again, now reinforced by the thousands. The two lines began to trade volleys creating what General Milroy remembered as "a perfect hurricane of balls." The Federal battery on the hill slope now opened fire hurling grapeshot and canister at the enemy directly over the heads of the West Virginians. The artillery fire was passing so close to Samuel and those around him that they were being showered with sparks and flaming bits of flannel from the canister rounds, burning their clothes and skin. As the artillery fire found its mark, huge gaps were cut in the still advancing Confederate line.

As the intensity of the fight increased, the Union defenders in the Sudley Road slowly began to give way under the weight of the Southern assault. The Georgians had closed to within 50 yards now and the volleys of rifle fire between the two lines were even more vicious. The regiment on the 3rd's left began to break up and, then, it stampeded to the rear. The 3rd still held but, gradually, men started to leave in twos and threes. The core of the regiment, however, was still holding, slowing the Southern advance. Then, as cartridge boxes emptied, men began to cry out for ammunition. The situation was becoming perilous, so Major Lang ordered a retreat up the hill. Under tremendous fire, the 3rd fell back with good discipline, firing its few remaining rounds as it went. By now, however, Sykes' two brigades as well as Reno's division were in place at the crest of Henry House Hill. As the 3rd passed through their ranks, the defense of Henry House Hill resumed. The hill was held until nightfall and, in the midst of a sudden, violent thunderstorm, Pope's Army of Virginia went into a general retreat, withdrawing towards Chantilly. Lee initially tried to pursue Pope, but following a brief battle at Chantilly, he decided to regroup and invade Mary land.

As the intensity of the fight increased, the Union defenders in the Sudley Road slowly began to give way under the weight of the Southern assault. The Georgians had closed to within 50 yards now and the volleys of rifle fire between the two lines were even more vicious. The regiment on the 3rd's left began to break up and, then, it stampeded to the rear. The 3rd still held but, gradually, men started to leave in twos and threes. The core of the regiment, however, was still holding, slowing the Southern advance. Then, as cartridge boxes emptied, men began to cry out for ammunition. The situation was becoming perilous, so Major Lang ordered a retreat up the hill. Under tremendous fire, the 3rd fell back with good discipline, firing its few remaining rounds as it went. By now, however, Sykes' two brigades as well as Reno's division were in place at the crest of Henry House Hill. As the 3rd passed through their ranks, the defense of Henry House Hill resumed. The hill was held until nightfall and, in the midst of a sudden, violent thunderstorm, Pope's Army of Virginia went into a general retreat, withdrawing towards Chantilly. Lee initially tried to pursue Pope, but following a brief battle at Chantilly, he decided to regroup and invade Mary land.

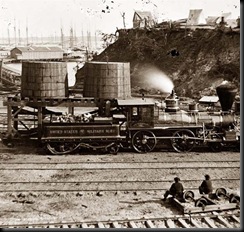

As a result of the defeat at Second Manassas, the Army of Virginia ended its short life and was disbanded in October 1862. As a part of that process, the 3rd West Virginia boarded a train on September 30, 1862 and was shipped back to West Virginia. They arrived in Clarksburg on October 1 and Samuel's company was sent further west to Parkersburg. Once there, they moved by steamship down the Ohio River to Point Pleasant. However, no sooner had they arrived than orders were received to go back to Clarksburg, where they finally camped in late October. From November 1862 to April 1863, the 3rd was assigned to patrol a line from Buckhannon west to Glenville. They were stationed near a small town named Bulltown. During this period, Samuel's military records indicate that he took leave, probably visiting the family farm near Nobe, only 28 miles from Bulltown. It would be the last time he would see his family.

In the spring of 1863, the 3rd underwent a major change as a part of a realignment in the Department of West Virginia. Before going into the details of this realignment, however, a word or two must be said about West Virginia as a theater of war and the War Department's attitude toward it. Quite frankly, from an 1860's view of warfare, West Virginia had little to recommend it as a theater of military operations. Its scenery of high, wooded ridges and fertile, well- watered valleys was magnificent-to look at. However, to a military commander, it was a nightmare. Its roads were few and poor, its settlements few and far between, and its people poor and ignorant. Nonetheless, the new state had strategic value to the North because it sat astride the flank of a long stretch of Confederate territory. As a result, Union forces could be in position to move southeast, toward the upper Shenandoah Valley and the critical Virginia Central Railroad, or south toward the increasingly vital Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, which ran in a northeast-southwest direction across the southeastern comer of West Virginia. But, conditions were never right for the North to take advantage of these strategic opportunities. While rugged terrain and poor communications were handicaps that could be overcome, no one seemed able to overcome the War Department's opinion that West Virginia was nothing but a sideshow, a poor stepchild orphan to the real war being fought in Virginia and in the West.

The lack of importance the Union's military leadership attached to West Virginia was reflected in the assignments to command in the area of officers whose performance in more important posts had been, for whatever reason, valid or invalid, judged to be less than satisfactory. One of these officers, William W. Averell would become important to Samuel and the men of the 3rd. Averell was a West Point graduate and 10-year veteran of the U.S. Army who had run afoul of General Joseph Hooker, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker blamed Averell for failures during Stoneman's Raid, a critical part of Hooker's disastrous Chancellorsville campaign. So, as is often the case in the military, Averell was sent to do penance in what was perceived to be a backwater of the war.

The lack of importance the Union's military leadership attached to West Virginia was reflected in the assignments to command in the area of officers whose performance in more important posts had been, for whatever reason, valid or invalid, judged to be less than satisfactory. One of these officers, William W. Averell would become important to Samuel and the men of the 3rd. Averell was a West Point graduate and 10-year veteran of the U.S. Army who had run afoul of General Joseph Hooker, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker blamed Averell for failures during Stoneman's Raid, a critical part of Hooker's disastrous Chancellorsville campaign. So, as is often the case in the military, Averell was sent to do penance in what was perceived to be a backwater of the war.

In May 1863, Averell reported to General Benjamin F. Kelley, commander of the department, and was directed to assume command of what was to be called the 4th Separate Brigade, which would include the 3rd West Virginia Infantry Regiment. Averell assumed command on May 23, 1863 and discovered his brigade was an odd assortment, consisting of five infantry regiments, two artillery batteries, the 16th Illinois Cavalry, an independent company of Ohio cavalry, and one company each of the 1st and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry. Altogether, this strange group came to 3,855 officers and men. On the same day that Averell arrived to assume command, he received orders to begin converting the 2nd, 3rd and 8th West Virginia Infantry to cavalry.

It would be an understatement to say this was not a smooth process. The three regiments were sent to a "camp of instruction" at Bridgeport, near Clarksburg, on June 6, 1863, where they found horses but no saddles, bridles, or other cavalry gear. This missing equipment finally arrived on June 14 and training began. It was fortunate that Samuel and his comrades were, for the most part, familiar enough with horses to stay on one for, on the day their gear arrived, so did orders to move out. Averell received a sequence of poorly worded orders from General Schenck's headquarters in Baltimore directing him to "push eastward, with all the means of reinforcement you can command, to New Creek," which was about 70 miles away. Averell reported that the 3rd West Virginia had been transformed from infantry to "cavalry in forty-eight hours, by mounting the men upon green horses." Moreover, "the horses were not shod," and he pointed out, "horses cannot travel over the rugged roads of this country without shoes, without breaking down very soon." So, for most of the month of July 1863, Samuel and his regiment got their "training" on the back of a horse, marching and countermarching in the are around Williamsport, Martinsburg, and Winchester, keeping an eye on Lee's army as it retreated from Gettysburg.

Then, on August 12, Averell received orders to take his command south to Huntersville where they were to "attack and capture, or drive out of the country" the Confederate troops of Colonel William L. Jackson. In addition, they were to destroy the saltpeter and gunpowder works in Pendleton County. Averell was then to move on to Lewisburg and "dispose of any force of the enemy that may be stationed there." Rather than strike out immediately, however, Averell chose to delay and resupply his brigade, which had been on the roads for over a month. The brigade urgently required horseshoes, horseshoe nails, clothing, salt, artillery ammunition, and, especially, small arms ammunition. By August 18, these needs had been met except for the critically needed small arms ammunition. However, Averell decided he could wait no longer. As a result, the brigade departed New Creek with only 35 rounds per man.

On August 21, the 3rd was in Huntersville, having endured a relatively uneventful march, with the exception of occasional harassing fire from bushwhackers. Once there, they discovered that Jackson and his men had abandoned their camp. So, the men of the 3rd set about destroying it. Pursuant to orders, Averell then began moving south toward Covington and White Sulpher Springs, from where he expected to move on to Lewisburg. However, on the morning of the August 26, Averell's lead element of the four-mile long column ran into a Confederate force of 1,900 infantry under the command of Colonel George S. Patton astride Rocky Gap. Lieutenant Colonel Thompson, the 3rd's new commander, aligned his six companies in dense woods and undergrowth opposite the right-center of the enemy's lines and the battle began. An all day firefight took place, with neither side being able to move the other.  Towards evening, both sides were running low on ammunition. Averell, believing that the enemy was about to be reinforced, ordered a retreat to begin the next morning. To aid the retreat, fires were lit to deceive Patton’s men and trees were felled across the road to impede any Confederate pursuit. On August 31, the 3rd reached Beverly, where they would remain in camp throughout September and October 1863.

Towards evening, both sides were running low on ammunition. Averell, believing that the enemy was about to be reinforced, ordered a retreat to begin the next morning. To aid the retreat, fires were lit to deceive Patton’s men and trees were felled across the road to impede any Confederate pursuit. On August 31, the 3rd reached Beverly, where they would remain in camp throughout September and October 1863.

On October 26, Averell received orders from General Kelley to proceed to Lewisburg, drive any Rebel forces out and then move on to the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad bridge over New River, near the town of Union, with the goal of destroying the bridge. This small campaign was discussed here on my article on the Battle of Droop Mountain. As Averell's brigade returned to New Creek from Droop Mountain, they prepared to go into winter encampment and several months of inactivity. However, within weeks, however, of arriving back in camp, Samuel's unit received orders to march. Many daring cavalry raids took place during the Civil War, operations that were glamorous and exciting, filled with rapid, decisive movements, panic and confusion and the destruction of key lines of communication and supply. Some, however, were noteworthy not for their glamour, but for their extreme difficulty, the tenacity of their commanders and the courage of the soldiers involved. The raid Averell was ordered to undertake would be an example of the latter.

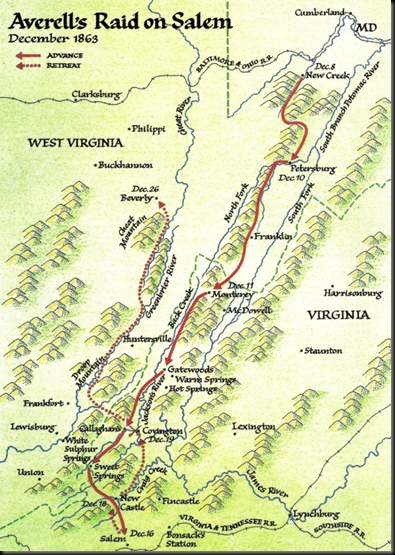

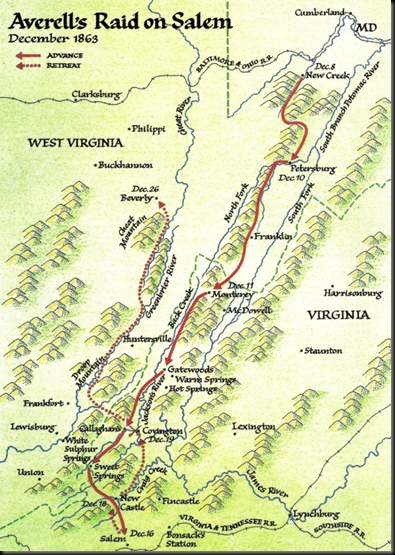

On December 5, 1863, General Benjamin Kelley ordered Averell to “proceed with all your available force now at New Creek, without delay, via Petersburg, Franklin, and Monterey, and then by the most practicable route to the line of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, at Bonsack’s Station, in Botetourt County, or Salem, in Roanoke County.” Once arrived at whatever destination he chose, Averell was to “destroy all the bridges, water-stations, and depots on the railroad in that neighborhood, and otherwise injure and destroy the road as far as possible by removing the rails and rendering them useless by heating and bending.” Kelley said that the operations were based on the “intimated” wishes of Maj. Gen. Halleck, general-in-chief of the Union Army.

The eastern end of the 204-mile Virginia & Tennessee line was at Lynchburg, where cars transferred to the Southside Railroad could continue their eastward trek to Petersburg and Richmond. Heading west from Lynchburg, the Virginia & Tennessee ran through southwestern Virginia until it ended at Bristol, Tennessee. At that point, the East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad took over and ran to Knoxville. Halleck wanted the Virginia & Tennessee cut to sever the vital network of railways that tied together the South’s Eastern and Western theaters and served as avenues for communications and supplies. The Virginia & Tennessee’s importance to the Confederacy was heightened by the fact that Southern troops under General Longstreet were operating in East Tennessee and had recently threatened Knoxville. By cutting the rail line, Union commanders hoped to deprive Longstreet’s men of needed materiel.

Kelley ordered Colonel Joseph Thoburn’s infantry to accompany Averell and guard his supply wagons. Averell, who chose Salem as his objective, foresaw the need for additional support in the form of multiple movements of Federal troops to confuse the enemy. After communicating those ideas to Kelley, Averell went to department headquarters in Cumberland, Maryland., on the evening of December 6 to develop a concerted plan of action.

Averell and Kelley’s complex plan called for four different commands, under General Eliakim P. Scammon, Colonel Augustus Moor, General Jeremiah Sullivan, and Colonel Thoburn, to seize various locations and hold them until Averell could reach his destination and make good his escape. Scammon was to move his forces out of the Kanawha Valley and arrive at Lewisburg on December 12, watching to the north and preventing any Confederate response from that direction. Moor’s command was to arrive just north of Huntersville on December 11, look for enemy activity in the direction of Lewisburg on the 12th and 13th and remain near of Frankfort until the 18th. Finally, Sullivan and Thoburn would threaten Staunton from different directions and keep enemy forces there from reacting to Averell’s presence. Moor and Thoburn were to receive their orders directly from Averell, while Kelley was to issue orders to Scammon and Sullivan. A key part of the deception involved threatening Staunton until December 20-21 in order to properly divert enemy attention.

Averell immediately returned to New Creek and rushed to complete preparations for the raid. On the morning of December 8, the brigade set out from New Creek. The weather that morning was described as “bright and beautiful,” but Averell reported–prophetically–having “many misgivings on account of our poor condition to overcome the wearying distances and confront the perils incident to such an expedition.”

The brigade, totaling some 2,500 men, headed southwest toward Petersburg, attempting to finish shoeing their mounts along the way. The lack of materials and a practical means of performing the chore while on the move, however, made effective efforts impossible. On December 10, the brigade arrived in Petersburg and was joined by Thoburn and his command of 700 infantry. The combined force continued southwest to Monterey, arriving there on December 11. At Monterey, the brigade drew supplies, along with forage for the horses. Averell had all men and officers who were judged to be unfit for the upcoming rough duty sent back to New Creek. On the morning of the 12th, in the midst of a driving, cold rainstorm–the portent of more poor weather to come–Thoburn’s command, along with most of the brigade’s supply train, turned southeast toward McDowell while Averell led his men southwest toward their objective at Salem.

The brigade, totaling some 2,500 men, headed southwest toward Petersburg, attempting to finish shoeing their mounts along the way. The lack of materials and a practical means of performing the chore while on the move, however, made effective efforts impossible. On December 10, the brigade arrived in Petersburg and was joined by Thoburn and his command of 700 infantry. The combined force continued southwest to Monterey, arriving there on December 11. At Monterey, the brigade drew supplies, along with forage for the horses. Averell had all men and officers who were judged to be unfit for the upcoming rough duty sent back to New Creek. On the morning of the 12th, in the midst of a driving, cold rainstorm–the portent of more poor weather to come–Thoburn’s command, along with most of the brigade’s supply train, turned southeast toward McDowell while Averell led his men southwest toward their objective at Salem.

Averell stayed off the main roads, instead moving the column down a rough path that ran beside Back Creek and occasionally climbing to run atop the steep ridgelines. The driving rain now mixed with sleet and snow, and an intensely cold wind blew from the north. The meandering path required the column to cross Back Creek no less than 13 times in the 23 miles from Monterey to Gatewoods. This was no easy task; the stream was rising steadily and was very swift.

As Averell’s command moved tortuously down Back Creek, the Confederate forces in the region began to react. Early on the morning of December 11, a patrol of 150 Partisan Rangers commanded by Captain Philip J. Thurmond encountered Scammon’s men on Big Sewell Mountain. The Confederates engaged the force long enough to discover that it was more than a meandering Federal patrol. General John Echols, notified by Thurmond, withdrew his forces from Lewisburg to a point two or three miles west, across the Greenbrier River.

Upon receiving a report from Echols at his headquarters in Dublin, West Virginia, on December 12, General Samuel Jones, commander of the Confederate Department of Western Virginia, sent dispatches to the adjutant general in Richmond and to General Lee at Orange Court House, reporting the situation and urgently requesting reinforcements. At the same time, Colonel William Jackson, commanding the 19th Virginia Cavalry, whose pickets had encountered Moor’s forces near Marling’s Bottom, received Echols’ dispatch and guessed that another Union force might be coming from the direction of New Creek or Hightown. Jackson then ordered a patrol under Captain Jacob Marshall that was positioned near Huntersville to retire to a position on Back Creek near Niter Cave, where elements necessary in the production of gunpowder were located, and watch for Federal movements. The small force would thus act as a tripwire directly in Averell’s path.

On the afternoon of December 13, Marshall’s patrol encountered Averell’s force, and a brief skirmish ensued. Averell believed the Southerners were the rear guard of Jackson’s command, and reported them to have been dispersed. Marshall, who was now cut off, destroyed the cave and sent a courier to Jackson to report Averell’s presence. At the same moment, Jackson also learned that another Federal force, probably Thoburn’s, was threatening Staunton, and “an opinion was expressed that they were going down the Bull Pasture River” to get to his rear. Jackson decided to fall back from his Warm Springs headquarters and moved all his forces to Hot Springs. So far, the Federal plan of deception was working. The Confederate troops in the region were forced to react to multiple threats from different points and thus were unable to focus on the real threat represented by Averell. The complex operation, however, would soon start to unravel.

As planned, Scammon forced Echols out of Lewisburg on December 12, while Moor approached the town from Marling’s Bottom. But Scammon, who apparently feared that he was going to be cut off by guerrilla action in his rear, pulled back from Lewisburg almost immediately. Moor, meanwhile, was trying to contact Scammon, who he assumed was still in Lewisburg. When his first messenger was captured by guerrillas, he sent a force of 20 cavalrymen to push their way through. They returned to Moor on the 14th to report that Lewisburg was deserted but that nearby Confederate forces had fired on them as they left the town. Realizing that he was unsupported, Moor retreated and arrived back in Beverly on December 17. A key part of the plan had collapsed. Confederate forces in the area would be able to focus on the real threat and converge on Averell once he showed his hand.

On the same day that Moor began his return to Beverly, Samuel and his comrades steadily moved toward Salem. The rain had not abated, and the Jackson’s River could scarcely be forded when the column reached it. The Federals pressed on, however, and reached Callaghan’s that afternoon. There, a dispatch arrived informing Averell that Scammon had taken Lewisburg and that Echols had pulled back. Averell, thinking his plan was still in place, decided to rest and feed the horses for a few hours. He also sent a small diversionary force down the road from Callaghan’s toward Covington.

At 2:00 a.m. the next morning, with the weather improving, the column moved forward in darkness. Averell kept the men moving, and by 10:00 a.m. on December 15, they reached Sweet Springs, where they again paused to rest.

During their recess, another dispatch reached Averell, this time telling him that Scammon had indeed abandoned Lewisburg and that Echols’ forces were some four miles from Union, West Virginia, to the north. Spurred by this news, Averell put the column back in motion at noon, and by 1:00 p.m. they had seized the road leading to New Castle. There, they captured a Confederate soldier who told them that as far as he knew no one was aware of their approach. When they were within 12 miles of New Castle, Averell decided to send out another diversion, this time dispatching a patrol toward Fincastle.

These diversions did have some effect. On the same morning that Averell was moving toward New Castle, Jones reported from Union that “the enemy was at Callaghan’s last night. Reported coming by Sweet Springs to this place. I think it probable they will go by Covington and strike the iron-works, perhaps at the railroad, via Fincastle.”

By nightfall, however, the Confederates were aware that Averell was a mere 28 miles from Salem and that the railroad was “in the utmost danger.” At 11:00 p.m., Jones sent another message to Richmond, stating: “I cannot throw any part of my force here [at Union] on the railroad in time to save it. You may be able to do so if you will send a force to check Averell on the railroad. I will endeavor to take care he does not escape through my department.”

All through the night of December 15, Averell pushed his brigade hard, determined to reach Salem by the next morning. Despite the brief rests the men and horses had enjoyed during the day, the hard march to Salem over that last week had taxed them. ‘The condition of the troops was bad,” Averell reported. “Many horses were broken down, more lame, [and] some of the men were obliged to walk.”

As morning broke, Samuel and the other the Union troopers were only four miles from Salem and could clearly hear trains in the distance. There they happened upon a group of Confederate soldiers who had ventured out seeking information about the reports of Federal troops. They now received that information firsthand. Averell questioned them individually in turn and learned thatGeneral Fitzhugh Lee’s Confederate cavalry had left Charlottesville two days earlier to intercept them. More important, Averell learned that a train containing troops to guard the railroad and supplies was expected to arrive in Salem at any minute. The Union general reacted to this news by sending an advance detachment of 350 men and two 3-inch guns galloping into Salem to seize the depot before the train arrived.

As ordered, this group dashed into Salem and set about feverishly preparing for the train’s arrival. They first cut the telegraph lines, then tore up the railroad tracks near the depot, positioned one gun, and took defensive positions. Within minutes the train, which was coming from Lynchburg, arrived loaded with Confederate troops. The Federals opened fire on it with the 3-inch gun. The first round missed, but a second shot went through the train diagonally. The engineer immediately stopped the train and began to back away. At that point, a third artillery round was fired at the train, which “hastened its movements,” claimed Averell.

Shortly thereafter, around 10 :00 a.m., Samuel and the rest of the brigade arrived in the town and began destroying as much of the rail facilities and supplies as they could. Parties of men were sent four miles east and 12 miles west down the line, where they set fire to five bridges and damaged as much track as possible. Meanwhile, in Salem, the depots and supplies were set ablaze, and three cars, a water station, and a turntable were destroyed. In addition, the telegraph lines were cut for about a half mile. As the depots burned, the supplies within were also destroyed. Averell’s report of the damage put the destruction at “two thousand barrels of flour, 10,000 bushels of wheat, 100,000 bushels of shelled corn, 50,000 bushels of oats, 2,000 barrels of meat, several cords of leather, 1,000 sacks of salt….” He also claimed a large amount of clothing and horse equipment was destroyed, along with 100 wagons and other miscellaneous items. The Confederate tally, however, claimed that only 148 barrels of flour, 150 bushels of wheat, and 180 bushels of corn were destroyed.

At 4:00 p.m., Averell withdrew from Salem, having created as much mayhem as he could in six hours. His men had covered 80 miles in the last 30 hours, so Averell decided to stop seven miles from Salem and rest a few hours. As the men dismounted, it began to rain and the temperature began to drop rapidly. Both nature and the Confederate army were closing in.

Armed with the knowledge that Averell had attacked Salem, the Confederate forces in the region quickly moved to block his escape. Jones realized correctly that his best chance was to cut off Averell’s escape routes and slow him down enough for converging superior forces to be brought to bear. Jackson’s command was in the best probable position to perform the critical task of blocking the passages back to Federal territory, and, on December 17, Jones ordered him to return to a position near Clifton Forge, about 15 miles northeast of Covington down Jackson’s River, and await further orders. At first light that morning, Jackson took a position near Jackson’s River Depot, where he could monitor a route through nearby Rich Patch and another through Clifton Forge, a few miles to the east. Jackson then sent out scouts toward Buchanan and Rich Patch. Detached from the Army of Northern Virginia, General Jubal Early had troops approaching Clifton Forge, but after receiving reports that Averell was returning to Salem, he diverted them to Buchanan.

Averell and his weary troopers’ route now took them along the bottom of Craig’s Creek, and the deluge of freezing rain that had begun on the 16th continued unabated, turning the creek into a swollen, churning torrent. The stream’s meandering route forced the brigade to cross it again and again, as many as seven times in only 10 or 12 miles. As the men led their mounts into the freezing water, the horses sank to midrib. Their riders soon found that the current was so fast they had to turn their horses upstream and make them straddle sideways across the water. If they failed to perform this tricky maneuver properly, the current striking the horse in the side would sweep both horse and rider into the torrent, and several men were drowned as a result. The icy temperature took its toll, and soon the soldiers’ uniforms were frozen stiff and the horses were covered with icicles. After a few crossings, the horses began to balk and had to be whipped and spurred to force them back into the raging waters. Ammunition became soaked and unusable. Averell began to fear that his command would be unable to fight effectively if they ran into Confederate resistance. Therefore, he kept the brigade moving throughout the 17th, into the night and on until sundown on the 18th, when they finally reached New Castle once again. Samuel and all the other troopers were soaked, freezing cold, muddy, and hungry. They dismounted to rest and eat, but within a few hours Averell received news that Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry was nearby at Fincastle and that Jones was between the Union troopers and Sweet Springs. At 9:00 p.m., the Federal commander reluctantly ordered the brigade to move out again, a detachment making another false advance toward Fincastle while the remainder of the brigade continued toward Sweet Springs.

Ammunition became soaked and unusable. Averell began to fear that his command would be unable to fight effectively if they ran into Confederate resistance. Therefore, he kept the brigade moving throughout the 17th, into the night and on until sundown on the 18th, when they finally reached New Castle once again. Samuel and all the other troopers were soaked, freezing cold, muddy, and hungry. They dismounted to rest and eat, but within a few hours Averell received news that Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry was nearby at Fincastle and that Jones was between the Union troopers and Sweet Springs. At 9:00 p.m., the Federal commander reluctantly ordered the brigade to move out again, a detachment making another false advance toward Fincastle while the remainder of the brigade continued toward Sweet Springs.

Within a few hours,the Federals ran into Jones’ pickets and skirmished with them, driving the Confederates back 12 miles, beyond the junction of the Fincastle Pike and the road to Sweet Springs. Averell assessed the situation. Lee was very close to his right and rear, and he knew he could not get through Sweet Springs without a fight that his weary men might not be up to. Averell saw that he had only two choices: He could move back to the southwest, around Jones’ right flank, through Monroe and Greenbrier counties, or he could move northeast to the Covington and Fincastle Pike. The former was the most circuitous route, while the latter was the most direct and therefore potentially dangerous. Averell chose the latter, rationalizing that the Confederates might not expect it.

The brigade moved forward once again, this time toward Covington, along a road described as a “deep, narrow defile.” The roadbed was covered in ice, and horses repeatedly slipped and fell, slowing the advance. But Averell and his officers kept the command moving, and by midday on December 19, they were nearing Covington and the climax of the raid.

At noon on the 19th, Averell’s brigade reached the Fincastle Pike, some 15 miles from the Island Ford Bridge across Jackson’s River, five miles below Covington. Reports came into Averell that the river was unfordable and filled with ice floes–securing the span was the only option. The brigade quickly moved forward and, eight miles from the river, ran into a militia unit of 300 mounted men, which they pushed aside. Averell dispatched a force to closely pursue the militia and secure the bridge. What Averell did not know was that the span had already been prepared for burning as soon as the Confederates received word of the approaching Federal force. But his men moved too swiftly, reaching the bridge at a gallop and preventing its destruction. By 9:00 p.m. the four-mile-long main Federal column had reached the Island Ford Bridge and begun crossing.

Meanwhile, Jackson and a motley force of cavalry and militia tried to cut off Averell. The colonel had elected to move his men to the intersection of the Rich Patch and Covington roads. It was dark by the time he reached that point, and he soon discovered to his horror that Averell’s force had taken a shortcut off the Rich Patch Road. Most of the Federal column had already crossed the bridge. Jackson sent Colonel William Arnett and his 20th Virginia Cavalry up the Rich Patch Road to pin down the end of the column while he led the rest of his men toward the bridge. As a result, a night engagement, a rare event in the Civil War, ensued.

By that time, all of Averell’s brigade except the 14th Pennsylvania, a rear guard force, and some of the ambulances and supply wagons had crossed the bridge. Jackson’s men arrived and cut off the bridge, and Arnett’s men fell upon the 14th Pennsylvania, which continued to fight its way forward. But, despite three attempts, the Federals could not reach the bridge. As morning approached, Averell sent word to the cut-off regiment to try to find another way across. He then set fire to the bridge to stop Jackson from following.

As the bridge burned, Colonel Arnett pulled back to prevent the 14th Pennsylvania from escaping via a nearby railroad bridge. This was a mistake. The besieged Federal cavalry instead took a pathway down into the river gorge and, despite the high, icy waters, managed to swim to the other side, losing four men who drowned. The regiment speedily rejoined the brigade and continued the journey back to Union lines.

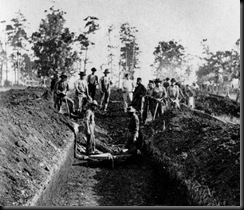

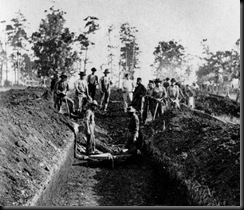

But, what became of Samuel Snider? A part of the rear guard force, he was cut off from the river and captured. As the brigade continued north to Beverly, Samuel was marched eastward for a week, arriving at Belle Isle Prison in Richmond on Christmas Day, 1863. Belle Isle was a barren wind-swept rock of about ten acres in the middle of the James River. There were about 6,000 men imprisoned there, living in the open in crude tents made from blankets and other linens, guarded by "soldiers" who were typical of the wretches who have always been used as military jailers. In the cold of December, between ten and thirty men were dying a day from starvation and exposure. But, little did Samuel and his fellow prisoners know that an even worse place was, at that very moment, being prepared for them-Andersonville Prison, Georgia.

In early February 1864, Samuel Snider was among the first load of prisoners put on a southbound train for Andersonville. On February 20, they arrived to find a crude stockade surrounding a huge 27-acre open area. There were no barracks, no mess facilities, no shelter of any kind. The camp was commanded by a Swiss immigrant officer, Captain Henry Wirz. Wirz was an ill-tempered brute of a man, angered by the loss of an arm at the Battle of Seven Pines in 1862 as well as his assignment to jailer's duties.

The prison at Andersonville was intended to hold a maximum of 13,000 prisoners. However, by March 1, a mere nine days after it opened, the prison held 7,500. By May 1, that number had ballooned to 15,000 and, by the beginning of August, the prison population would reach a staggering total of 33,000 men.

The prison at Andersonville was intended to hold a maximum of 13,000 prisoners. However, by March 1, a mere nine days after it opened, the prison held 7,500. By May 1, that number had ballooned to 15,000 and, by the beginning of August, the prison population would reach a staggering total of 33,000 men.

Supplies of food and medicine from an already strapped Confederacy were virtually nonexistent and Wirz had no ability or inclination to influence the system for more. Daily rations consisted of two tablespoons of beans, one tablespoon of molasses and a half-pint of rough cornmeal, which was likened by one prisoner to digesting ground glass. The only source of water was a foul creek that ran through the center of the stockade, perversely called Sweet Water Branch. It also served as the garbage dump for the hospital and cookhouse. In addition, seepage from the latrines, built a few yards parallel to the creek, added a putrid green color and sickening odor to the lice and mosquito infested stream. As for the men, they dressed in the tattered remains of their uniforms and lived in the open, usually in a small hole dug in the mud and covered by a blanket.

As a result of these horrific conditions, Andersonville rapidly became nothing more than a vast, ill-organized, unequipped hospital. Everyone was sick and those who wandered across the so-called "death line" were shot by the guards and were considered fortunate. By August 1864, the death rate soared to over 100 men per day. One of those struck down was Samuel Snider.

Samuel became ill with a common malady at Andersonville: Scorbutus. Caused by inadequate diet, especially the absence of vegetables and fruits, it manifests itself in diarrhea, then fever and, finally, ulcers all over the body. Eventually, even the teeth loosen and fall out. On August 2, Samuel was admitted to  the "hospital," a place so awful many men preferred to suffer in camp among friends rather than go there, for to go there always meant death. So it was for Samuel, who died on August 5, 1864. He was moved to the "dead house" where his big toes were tied together and a name, company and regiment tag was fastened to him. Then, he was loaded on the "dead wagon" by a team of black slaves who buried him in a narrow pit with the others who had died that day.

the "hospital," a place so awful many men preferred to suffer in camp among friends rather than go there, for to go there always meant death. So it was for Samuel, who died on August 5, 1864. He was moved to the "dead house" where his big toes were tied together and a name, company and regiment tag was fastened to him. Then, he was loaded on the "dead wagon" by a team of black slaves who buried him in a narrow pit with the others who had died that day.

After the war, Captain Wirz was tried and convicted of war crimes-the only war criminal of the Civil War. While his trial may have been a circus and, with the outcome a certainty, far from fair, I have always believed that his hanging was justly and richly deserved.

After the war, Captain Wirz was tried and convicted of war crimes-the only war criminal of the Civil War. While his trial may have been a circus and, with the outcome a certainty, far from fair, I have always believed that his hanging was justly and richly deserved.

In the summer of 1865, the Government dispatched Clara Barton, the legendary founder of the American Red Cross, to Andersonville. Along with a surviving prisoner, Dorence Atwater, who had kept a secret list of all those who died, she set about properly identifying and burying the dead of Andersonville. The result was Andersonville National Cemetery, formally established on July 26,1865. That day, Clara Barton wrote in her diary that, as she raised the U.S. flag, she was overcome by emotion: "Up and there it drooped as if in grief and sadness, till at length the sunlight streamed out and its beautiful folds filled--the men stuck up the Star Spangled Banner, and I covered my face and wept.”

In the summer of 1865, the Government dispatched Clara Barton, the legendary founder of the American Red Cross, to Andersonville. Along with a surviving prisoner, Dorence Atwater, who had kept a secret list of all those who died, she set about properly identifying and burying the dead of Andersonville. The result was Andersonville National Cemetery, formally established on July 26,1865. That day, Clara Barton wrote in her diary that, as she raised the U.S. flag, she was overcome by emotion: "Up and there it drooped as if in grief and sadness, till at length the sunlight streamed out and its beautiful folds filled--the men stuck up the Star Spangled Banner, and I covered my face and wept.”