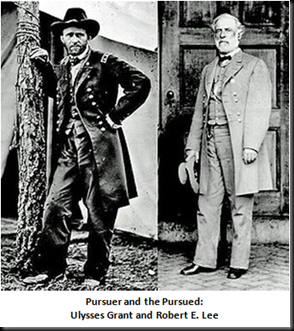

The story of the final days of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia is one filled with drama, as the tattered but defiant remains of his proud army retreated westward from Richmond and Petersburg with Federal forces under Ulysses S. Grant in pursuit. Lee’s last hope was to move west for resupply, then turn south to merge his forces with those under General Joe Johnston. With that accomplished, he would somehow continue the fight, even though that fight might appear utterly hopeless. It was a bold gambit and one made with the same audacity that had characterized Lee’s leadership throughout the war. However, it was also made in absolute desperation—there were no other options, it was now a matter of escape or surrender. At the same time, his pursuer was just as determined to cut him off, to capture his army, and effectively end the war.

The story of the final days of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia is one filled with drama, as the tattered but defiant remains of his proud army retreated westward from Richmond and Petersburg with Federal forces under Ulysses S. Grant in pursuit. Lee’s last hope was to move west for resupply, then turn south to merge his forces with those under General Joe Johnston. With that accomplished, he would somehow continue the fight, even though that fight might appear utterly hopeless. It was a bold gambit and one made with the same audacity that had characterized Lee’s leadership throughout the war. However, it was also made in absolute desperation—there were no other options, it was now a matter of escape or surrender. At the same time, his pursuer was just as determined to cut him off, to capture his army, and effectively end the war.

Monday, April 3, 1865

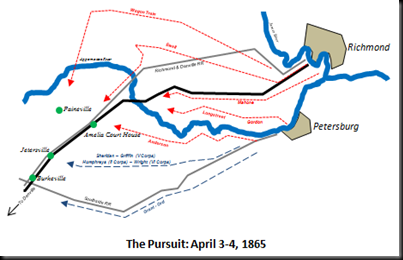

With the crushing defeat at Five Forks on April 1 and the Union breakthrough at Petersburg the following day, Lee realized that he had no choice but to abandon Petersburg and Richmond. At nightfall on April 2, his army, now numbering approximately 57,000 men, began their retreat. Lee’s plan was to get all his troops safely away, then consolidate and resupply at Amelia Court House, some 40 miles west of Petersburg. Then, the army would turn south and march 100 miles to Danville, where he hope to rendezvous with Johnston. Time, however, was the critical factor. As Lee’s men streamed west, they had a 12-hour lead on the Federal pursuit and that lead must be maintained if they were to be successful.

His biggest problem was that his army was moving west in four separate columns and three of those columns would have to find a way over the swollen Appomattox River if they were to reach Amelia Court House ahead of Grant’s army. Therefore, to eliminate any potential delays, Lee had each of those three column heading towards different crossing points. The most northern group consisted of men who had been manning the Richmond defenses, led by General Richard Ewell. They left Richmond, crossed the James River, and angled towards the Genito Bridge over the Appomattox. The second column, moving just south of Ewell’s, was led by General William Mahone. These troops had been in the trenches between Richmond and Petersburg across the narrow river peninsula known as the Bermuda Hundred. Mahone was ordered to effect a crossing of the Appomattox at Goode’s Bridge. The third column consisted of troops from the Petersburg defenses under Generals James Longstreet and John Gordon. They had crossed to the north side of the Appomattox as they departed Petersburg and would re-cross to the south side once they reached Bevill’s Bridge. The final column, meanwhile, was led by General Richard Anderson and included the remnants of George Pickett’s and Fitzhugh Lee’s commands, which had been shattered by Union General Phil Sheridan at Five Forks. This column was already south of the river and would march directly to Amelia Court House.

Lee himself followed Longstreet and Gordon’s men. Those with him remembered that he seemed almost happy as they rode west. One commented, “His expression was animated and buoyant, his seat in the saddle erect and commanding, and he seemed to look forward to assured success.” He told his staff that he had gotten the army safely away and out of the trenches, and that now Grant would have to extend his supply lines to pursue them, narrowing the odds in the process. His optimism was infectious to some degree and one member of Lee’s staff recalled that the men marching beside them seemed happy to finally be out of the trenches and in the open once more. However, these feelings were not universal among Lee’s troops. One lieutenant from South Carolina who was marching the in the column from Five Forks said:

Lee himself followed Longstreet and Gordon’s men. Those with him remembered that he seemed almost happy as they rode west. One commented, “His expression was animated and buoyant, his seat in the saddle erect and commanding, and he seemed to look forward to assured success.” He told his staff that he had gotten the army safely away and out of the trenches, and that now Grant would have to extend his supply lines to pursue them, narrowing the odds in the process. His optimism was infectious to some degree and one member of Lee’s staff recalled that the men marching beside them seemed happy to finally be out of the trenches and in the open once more. However, these feelings were not universal among Lee’s troops. One lieutenant from South Carolina who was marching the in the column from Five Forks said:

There was an attempt to organize the various commands, to no avail. The Confederacy was considered as “gone up”' and every man felt it his duty, as well as his privilege, to save himself. There was no insubordination…but the whole left of the army…struggled along without strength, and almost without thought. So we moved on in disorder, keeping no regular column, no regular pace. When a soldier became weary, he fell out, ate his scanty rations-if, indeed, he had any-rested, rose and resumed the march…There were not many words spoken. An indescribable sadness weighed upon us. The men were very gentle toward each other.

As for Lee’s pursuers, Grant’s troops entered Richmond and Petersburg in the early morning hours of April 3. The night before, his staff and some of his commanders had urged a renewed assault on Petersburg, but Grant would not agree to that, telling them, “They will evacuate tonight and there’s no need for sacrifice.” That comment and several of Grant’s actions in the days that followed indicate a sincere desire on his part to capture Lee’s army rather than destroy it, which had been his objective up this moment. Now, with the end in sight, he seemed to genuinely want to end the war with as little loss of life as possible. In fact, as he entered Petersburg that morning, the man whom some had referred to as “The Butcher” restrained himself and others from attacking the retreating Confederate army.

General Meade and I entered Petersburg on the morning of the 3d and took a position under cover of a house which protected us from the enemies' musketry which was flying thick and fast there. As we would occasionally look around the corner we could see the streets and the Appomattox bottom, presumably near the bridge, packed with the Confederate army. I did not have artillery brought up, because I was sure Lee was trying to make his escape, and I wanted to push immediately in pursuit. At all events I had not the heart to turn the artillery upon such a mass of defeated and fleeing men, and I hoped to capture them soon.

Once the city was secure, Grant met with President Lincoln, who had been staying nearby at City Point and he explained his plan to pursue Lee. Rather than simply follow Lee’s army, his plan was to make every effort to cut them off, sealing off any route south, and preventing Lee from consolidating with Johnston. Therefore, Grant would move his men along the south side of the Appomattox River on a parallel course to Lee’s. The problem he faced was Lee’s 12-hour lead.

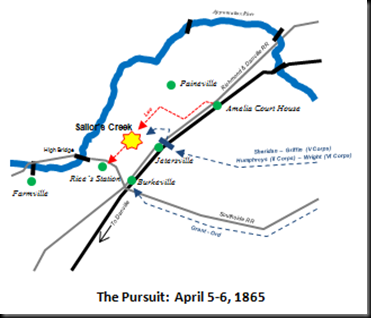

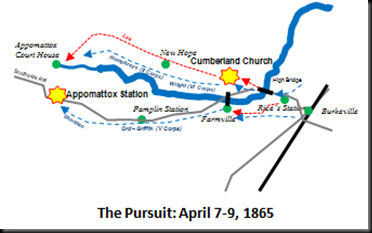

Examining the map, Grant could see that, while Lee had several bridges available to get across the Appomattox River, the main road to Danville, as well as the Danville Railroad, ran through the town of Burkeville, some 12 miles southwest of Amelia Court House. If he could cut off that route, he might very well bag Lee’s army right there. He had sent Phil Sheridan and his cavalry galloping off the night before towards Jetersville, which lay just north of Burkeville, and, by now, they were already as far west as Lee. They would have no problem reaching Jetersville and the road to Burkeville before Lee, blocking the way south. So, he ordered General Meade and the infantry from the Army of the Potomac to follow Sheridan and be prepared to support him. General Griffith’s V Corps was on the road first, followed closely by General Humphrey’s II Corps and General Wright’s VI Corps. In addition, General Ord’s Army of the James with its XXIV and XXV Corps would march on a parallel track to the south along the Southside Railroad toward Burkeville itself, and Grant elected to ride with them.

The chase was on.

Tuesday, April 4, 1864

The morning of April 4 came with a cold drizzle and stone gray skies. Robert E. Lee crossed the Appomattox with his staff around 7:00 a.m., heading for Amelia Court House, where the 350,000 rations he requested were to be waiting. The initial news he received on the position of his army was not as good as he had hoped. Longstreet and Gordon had discovered that Bevill’s bridge was washed out by flooding and they were forced to use Goode’s Bridge. When they arrived there, they found Mahone’s troops were still crowding the approach to the bridge, and, while they did get across the Appomattox, their crossing was delayed for several hours, cutting into the 12-hour lead Lee had on Grant. Meanwhile, Ewell had also run into problems getting his men across the river. Materials he needed to shore up the Genito Bridge had not arrived when promised, and he was forced to use the Mattoax Railroad Bridge instead. This required that his men lay down wooden planks, and that, combined with the narrow width of the bridge would delay his arrival at Amelia Court House until nightfall.

But the worst news came when Lee rode into Amelia Court House around 7:30 a.m. Instead of 350,000 rations, the quartermaster had sent him carloads of unneeded ammunition and artillery shells, but no food for his starving soldiers. Lee was devastated by the discovery. One officer later wrote that Lee’s face reflected “intense agony” and another said, “The failure of of the supply of rations completely paralyzed him. An anxious and haggard expression came to his face.”

Lee had planned to just pause at Amelia Court House long enough to distribute food and consolidate the four columns of his army. Now, there was no food and his army was behind schedule in arriving. Plus, they could not go on without rations. He would be forced to forage in the country surrounding the town, further delaying his move south. His 12-hour lead on Grant had evaporated and there was nothing that could be done to get it back. So, he focused on the immediate need to find food, first issuing a proclamation to the “Citizens of Amelia County, Virginia” asking that they come forth with any meat, cattle, sheep, hogs, flour, meal, corn, and provender in any quantity that can be spared.” He then composed an urgent telegram to Confederate authorities in Danville requesting that 300,000 rations be shipped immediately to Burkeville. Since the telegraph lines were down between Amelia Court House and Burkeville, he gave the telegram to a dispatch rider and sent him riding on a mule south to Burkeville, where it would go out over the lines to Danville. In addition, he also sent copies of the message for delivery to the quartermaster in Lynchburg.

Unfortunately for Lee, his dispatch rider would find that Phil Sheridan and his Federal cavalry were already in Jetersville, blocking the road to Burkeville. Sheridan had sent two of his divisions under George Crook and Wesley Merritt north, ordering them to attack and harass any expose portions of Anderson’s column from Five Forks. This they did with great effectiveness, dashing into the Confederate column as it stretched westward, cutting down men and animals alike. Soon, the road toward Amelia Court House was littered with burning wagons and dead and wounded Confederate soldiers, and lined with prisoners moving east back towards Petersburg. The third division of Sheridan’s command, meanwhile, rode towards Jetersville, with Sheridan riding hard in the advance along with only 200 troopers.

Unfortunately for Lee, his dispatch rider would find that Phil Sheridan and his Federal cavalry were already in Jetersville, blocking the road to Burkeville. Sheridan had sent two of his divisions under George Crook and Wesley Merritt north, ordering them to attack and harass any expose portions of Anderson’s column from Five Forks. This they did with great effectiveness, dashing into the Confederate column as it stretched westward, cutting down men and animals alike. Soon, the road toward Amelia Court House was littered with burning wagons and dead and wounded Confederate soldiers, and lined with prisoners moving east back towards Petersburg. The third division of Sheridan’s command, meanwhile, rode towards Jetersville, with Sheridan riding hard in the advance along with only 200 troopers.

At 4:00 p.m., he and his escort arrived there, followed in short order by the rest of his remaining division. Seeing that Lee had yet to arrive, he sent a dispatch to General Griffin, telling him to move the V Corps quickly along and help him block the road to Burkeville. The infantry began to arrive around 5:00 p.m., and quickly began to dig in along the road. However, before they arrived, Sheridan’s troopers captured Lee’s dispatch rider. When Sheridan read the message he was carrying, he decided to let it go through to both Danville and Lynchburg, realizing that this might allow Federal forces to intercept the much needed rations before they got to Lee.

Of course, there was the problem of how to get the messages through since he had captured Lee’s rider. However, Sheridan had a ready solution. He had created a special command of 30-40 men under Major Henry Young just for this kind of mission. Young and his men were clothed in Confederate uniforms and had well-practiced Virginia drawls. They would carry the dispatch forward and ensure it was received by Confederate authorities. In fact, throughout the pursuit, Young and his men would ride among Lee’s column gathering information, and, at the same time, distributing false instructions and orders, creating great confusion in the process.

Of course, there was the problem of how to get the messages through since he had captured Lee’s rider. However, Sheridan had a ready solution. He had created a special command of 30-40 men under Major Henry Young just for this kind of mission. Young and his men were clothed in Confederate uniforms and had well-practiced Virginia drawls. They would carry the dispatch forward and ensure it was received by Confederate authorities. In fact, throughout the pursuit, Young and his men would ride among Lee’s column gathering information, and, at the same time, distributing false instructions and orders, creating great confusion in the process.

As the sun set, Lee remained at Amelia Court House, six miles north of Sheridan. Ewell and Anderson were finally arriving and the army was at last consolidated. However, as darkness closed in, he could hear the unmistakable sounds of carbine and rifle fire in the distance. He knew that meant Union cavalry must be lurking nearby, but exactly where and in what force he was not sure. As a result, he remained oblivious to the knowledge that his escape route south was now blocked by Union infantry and cavalry. However, he had to know that, with the loss of those precious 12-hours, the noose around him was being tightened with every passing minute.

Wednesday, April 5, 1865

When Lee arose on Wednesday morning, Tuesday’s cold drizzle had turned to a hard, soaking rain. And, with it, came yet more bad news: His Commissary General’s wagons were returning from their foraging task mostly empty. There was no food to be had in Amelia County. Lee had no choice but to order the destruction of all surplus ammunition and supplies, and then direct the army south towards Danville. Cavalry under the command of his son, Rooney, led the way, followed closely by some of Mahone’s infantry. Shortly after leaving Amelia Court House, he received the news that a supply train from Ewell’s column that had been sent circling west of the main body so as to prevent Federal cavalry from destroying it, had met that very fate. That morning, Phil Sheridan had sent some of Crook’s troopers in a sweep westward to be sure Lee had not turned that way. The Union cavalry had come upon Ewell’s wagons near Paineville and attacked them. They swept down on the supply train and virtually annihilated it, leaving with over 1,000 prisoners in tow and a mass of burning wagons clogging the narrow road.

Then, at 1:00 p.m., as Lee rode alongside his “Old Warhorse,” General Longstreet, word came that the road ahead was blocked. Lee and Longstreet rode forward, where Rooney Lee reported the situation. A line of Union skirmishers lay directly ahead and, behind them, a solid wall of blue-clad infantry was dug in across the road at Jetersville. Lee received this news with great anxiety and hesitated a long time before making a decision. Longstreet urged an attack, but Lee did not want to bring on a general battle. With the road to Danville closed, he had few options available. He issued orders for the army to turn and shift direction from south to west. They would leave a strong rear guard in front of the Federal troops to mask their departure while the main body of the army circled west to Amelia Springs, clinging to the Southside Railroad as their last potential lifeline for rations hopefully coming from Lynchburg.

Then, at 1:00 p.m., as Lee rode alongside his “Old Warhorse,” General Longstreet, word came that the road ahead was blocked. Lee and Longstreet rode forward, where Rooney Lee reported the situation. A line of Union skirmishers lay directly ahead and, behind them, a solid wall of blue-clad infantry was dug in across the road at Jetersville. Lee received this news with great anxiety and hesitated a long time before making a decision. Longstreet urged an attack, but Lee did not want to bring on a general battle. With the road to Danville closed, he had few options available. He issued orders for the army to turn and shift direction from south to west. They would leave a strong rear guard in front of the Federal troops to mask their departure while the main body of the army circled west to Amelia Springs, clinging to the Southside Railroad as their last potential lifeline for rations hopefully coming from Lynchburg.

Sheridan waited impatiently for Lee to attack as the afternoon wore on, but no assault came. However, once word was received that his men had plundered Ewell’s supply wagons far to the west of the Danville Road, Sheridan became convinced that Lee had turned that direction. He went to General Meade, who had arrived with the II and VI Corps and proposed they head west in pursuit. But the irascible Meade, who had been openly feuding with Sheridan since the previous summer, disagreed with his analysis. Meade was convinced that Lee was going to make a stand at Amelia Court House. As the ranking officer on the scene, he issued orders for an attack at first light on April 6.

Sheridan decided to go over Meade’s head and sent an urgent message to Grant detailing the situation and his belief that Lee had headed west. The dispatch rider carrying the message found Grant, who was still traveling with Ord’s column, at sunset. Grant read Sheridan’s report and immediately set off with a small escort to Jetersville. Grant arrived at 10:30 p.m. and met with both Sheridan and Meade. He listened to both men, then issued orders for the planned attack to go ahead. However, he added that he also expected Lee to continue the retreat and, should that prove true, the army needed to be prepared to immediately continue the pursuit.

Meanwhile, Lee and his army spent a wet night on the move over narrow, muddy roads toward Amelia Springs. The going was slow and tortuous and became even more so when they found the smoldering remains of Ewell’s wagons blocking their path at Paineville. The sight of the destroyed supply wagons seemed to make many men’s spirits sag even further. Onward they plodded, through the mud, wondering what the next day might bring.

Thursday, April 6, 1865

When the sun began to rise on April 6, one Confederate officer remembered, “I beheld the first signs of dissolution of that grand army…when looking over the hills I saw swarms of stragglers moving in every direction.” In addition, every road coming into Amelia Springs was littered with abandoned rifles and haversacks, and more covered the fields nearby, where Lee’s men dropped them as they abandoned the line of march, heading off in one’s and two’s, seeking either a Federal patrol to surrender to or hoping to find a safe way home.

When Lee arrived at Amelia Springs early that morning, his Commissary General told him that 80,000 rations were waiting in railcars along the Southside Railroad at Farmville, some 19 miles ahead. He asked Lee if he wanted the rations moved forward or left at Farmville. After some thought, Lee elected to leave them in place, fearing that Federal cavalry might intercept them if he tried to have them brought east. He then issued orders for the army to continue its march towards Farmville. If they could make Rice’s Station today, they would only have a few more miles to go to get to the waiting rations. Longstreet’s Corps moved out immediately and was well on its way to Farmville by mid-morning, with Anderson, Ewell, and Gordon’s commands trailing close behind.

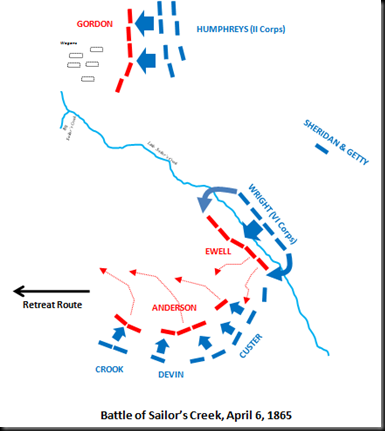

Unfortunately, their progress soon slowed. The roads leading out of Amelia Springs were relatively straight for the first three miles, but then began to twist, loop, and meander through hills and over streams. The army began to bunch up, then break up as wagons stuck in the mud, blocking the roads to the infantry following them. As gaps appeared in the columns, Sheridan’s cavalry began to strike again, smashing into any isolated groups. Many of these attacks were small, but a few were quite large and, while Lee’s men would turn them back, these intermittent firefights were causing progress to slow even more and stretch the columns out even longer. Worst of all, at 2:00 p.m., as the army approached a small valley formed by Sailor’s Creek, a large gap opened between the end of Longstreet’s column and the head of Anderson’s. This gap was quickly exploited by Phil Sheridan.

Before anyone in either Longstreet or Anderson’s commands realized it, Sheridan thrust all three of his cavalry divisions under Crook, Merritt, and Custer into the gap, cutting off the road ahead and bottling up Anderson, Ewell, and Gordon. Worst of all for the Confederates, Humphreys’ II Corps had been nipping at Gordon’s heals all morning, and Wright’s VI Corps was right behind Humphreys. Humphreys’ dogged pursuit quickly had become a series of sharp engagements, which he later described as follows.

A sharp, running fight…continued over a distance of fourteen miles, during which several partially entrenched positions were carried. The country was broken, wooded with dense undergrowth and swamps, alternating with open fields…for miles the road being strewn with tents, camp equipage, baggage, battery forges, limbers and wagons.

Fitz Lee’s cavalry first discovered the mass of Federal cavalry ahead and their commander rode back to tell Anderson the dire news. Anderson knew he was in a tough spot and he looked about him at the terrain surrounding Sailor’s Creek. The valley consisted of a narrow lowland surrounded by bluffs, and was only about 800 yards wide, running roughly northwest to southeast. The main road his men were traveling on was just south and west of the valley, and there was a smaller road looping north about two miles away.

Anderson ordered his men into line of battle facing the enemy cavalry and sent word to Ewell and Gordon telling them what was happening. When Ewell received the message, he began to deploy his men in support of Anderson and ordered the supply wagons between his command and Gordon’s to break off the main road and take the smaller one to the north, hoping they might escape Union cavalry. Now, confusion set in as Gordon, upon seeing the wagons head off the north, elected to follow them, unbeknownst to either Anderson or Ewell. The infantry from the pursuing II Corps stayed on Gordon’s rear and the VI Corps quickly sped up their march, closing in on the trailing end of Ewell’s column.

In very short order, Anderson and Ewell found themselves trapped on the hills above Sailor’s Creek. Sheridan’s cavalry was in front of Anderson, and Ewell soon found VI Corps forming in lines to attack him from his rear. Both Confederate commands were now essentially deployed back-to-back, boxed in, and forced to fight. Meanwhile, to the north, Gordon’s men were waiting as the wagons ahead of them tried to pass over Sailor’s Creek across two flimsy bridges, allowing II Corps to catch up with them. Gordon was also forced to deploy his men and hope he could hold off the impending attack and get his men across the creek.

In very short order, Anderson and Ewell found themselves trapped on the hills above Sailor’s Creek. Sheridan’s cavalry was in front of Anderson, and Ewell soon found VI Corps forming in lines to attack him from his rear. Both Confederate commands were now essentially deployed back-to-back, boxed in, and forced to fight. Meanwhile, to the north, Gordon’s men were waiting as the wagons ahead of them tried to pass over Sailor’s Creek across two flimsy bridges, allowing II Corps to catch up with them. Gordon was also forced to deploy his men and hope he could hold off the impending attack and get his men across the creek.

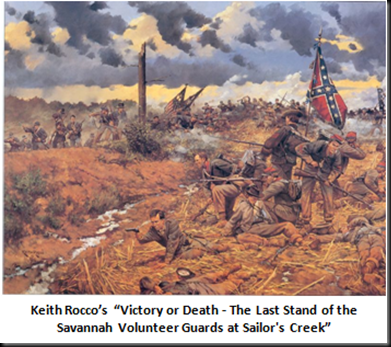

At 5:15 p.m., Union artillery from VI Corps opened fire on Ewell’s command. Ewell had no artillery with which to answer the barrage, and a heavy bombardment from 20 Federal guns continued unabated for 30 minutes. Then, Union infantry formed and began to advance towards the Confederate position through the clouds of smoke left by the artillery barrage. The Confederate defenders blasted volleys into them and the blue infantry broke briefly before a second line renewed the assault. The fighting was vicious and desperate. The VI Corps soon bent back both Ewell’s flanks and penetrated the center of his line where Federal soldiers fought hand-to-hand with sailors and marines from the Confederate Naval Battalion. One soldier from the 37th Massachusetts, a unit formed from men of the Berkshire Hills region of that state, remembered the fighting as follows:

They clubbed their muskets, fired pistols in each other's faces and used the bayonet savagely. One Berkshire man was stabbed in the chest by a bayonet and pinned to the ground as it came out near his spine. He reloaded his gun and killed the Confederate, who fell across him. The Massachusetts man threw him off, pulled out the bayonet, and despite the awful wound, walked to the rear.

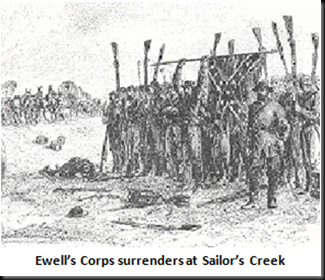

Notwithstanding the ferocity of their defense, the end was inevitable for Ewell and his men. The line finally broke, with Ewell losing over 3,000 of the 5,300 men he commanded, and Ewell himself being captured by a sergeant from the 5th Wisconsin.

Notwithstanding the ferocity of their defense, the end was inevitable for Ewell and his men. The line finally broke, with Ewell losing over 3,000 of the 5,300 men he commanded, and Ewell himself being captured by a sergeant from the 5th Wisconsin.

Immediately behind Ewell, things went no better for Anderson. His men managed to turn back several cavalry charges but a final mass assault by George Custer and Wesley Merritt’s troopers carried the line. After a brief but deadly fight within the Confederate lines in which the “saber, revolver and Spencer carbine of the cavalry were too much for the bayonet and the musket that could not be quickly loaded,” Anderson’s command collapsed with many of his men “scattering like children just out of school.” Anderson would find he had lost nearly 2,600 of the 6,000 men who had gone into the fight.

Gordon also fared little better. His soldiers held II Corps back for a short period before the sheer weight of the Union assault forced them back, where they mixed in with the wagons and all organized resistance ended. Gordon did manage to get some of his command across the creek but lost 2,000 men, three artillery pieces, 200 wagons, and 70 ambulances in the process.

Gordon also fared little better. His soldiers held II Corps back for a short period before the sheer weight of the Union assault forced them back, where they mixed in with the wagons and all organized resistance ended. Gordon did manage to get some of his command across the creek but lost 2,000 men, three artillery pieces, 200 wagons, and 70 ambulances in the process.

While all this was going on, Lee waited impatiently at Rice’s Station, where Longstreet’s Corps had already arrived. However, as soon as Lee noted the steady stream of soldiers had slowed to a trickle, he became anxious and the sound of cannon and rifle fire in the distance only added to his deep concern. He began to ride east up the road to see what was happening and quickly encountered the remnants of the disaster at Sailor’s Creek in the form of disorganized, retreating soldiers, many of them wounded and the rest appearing utterly demoralized. He was heard to say, ‘My God, has the army dissolved?” A short while later, he would tell an officer, “A few more Sailor’s Creeks and it will be over—ended.”

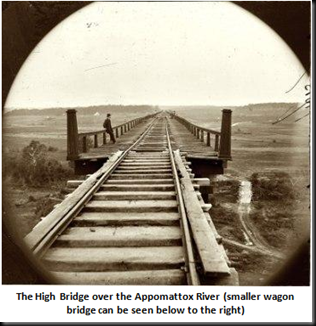

He returned to Rice’s Station and ordered Longstreet to move directly to Farmville, collect the rations waiting there, then cross the Appomattox River once again, and destroy the Farmville bridges behind him. Meanwhile, Mahone and the remnants of Gordon’s command would immediately cross the Appomattox via the High Bridge, a narrow rail bridge that stretched 150 feet above the river. Once they were across, a rear guard and some engineers would burn the rail bridge as well as a smaller wagon bridge below it. Lee’s hope was that, if he could get his army safely to the north side of the river, he could pause long enough to feed and rest them before moving on. It would prove to be a fatal error as the path towards Lynchburg and the additional supplies stored there was considerably longer that that south of the river. Plus, there would be no way to get back across the river to the railroad line until they reached the headwaters of the Appomattox River near a village called Appomattox Court House.

With nightfall, as Lee marched his tired army across the river, Sheridan sent a telegram to Grant, saying:

GENERAL: I have the honor to report that the enemy made a stand at the intersection of the Burke's Station road with the road upon which they were retreating. I attacked them with two divisions of the Sixth Army Corps and routed them handsomely, making a connection with the cavalry. I am still pressing on with both cavalry and infantry. Up to the present time we have captured Generals Ewell, Kershaw, Barton, Corse, De Foe [Du Bose], and Custis Lee, several thousand prisoners, 14 pieces of artillery, with caissons, and a large number of wagons. If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.

The next morning, President Lincoln saw a copy of Sheridan’s dispatch and immediately sent a telegram of his own to General Grant:

Gen. Sheridan says "If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender." Let the thing be pressed.

Friday, April 7, 1865

Before the sun was even up, Lee was in Farmville, overseeing the distribution of rations to Longstreet’s men. There was not much to be had, but it was better than nothing and it was the first regular rations the men had eaten since they left Petersburg four days before. A young private later recalled what he saw as the starving men received the first food some of them had seen in days.

Before the sun was even up, Lee was in Farmville, overseeing the distribution of rations to Longstreet’s men. There was not much to be had, but it was better than nothing and it was the first regular rations the men had eaten since they left Petersburg four days before. A young private later recalled what he saw as the starving men received the first food some of them had seen in days.

There were a few barrels of meal and a few middlings of meat scattered along the sidewalks. Without orders, the men charged that meal, with which they filled their pockets and any other available receptacles. The meat was seized upon and slashed into pieces as they ran. Several of the men stuck their bayonets into middlings and bore them proudly aloft.

However, in addition to the distribution of rations, the day would also see the first visible cracks in the resolve of Lee’s commanders. One incident involved General Henry Wise, the 60-year old former governor of Virginia. Wise had managed to get two brigades from his division away from Sailor’s Creek intact and, when he approached Lee that morning, the former governor exploded when Lee asked him for his assessment of the situation.

There is no situation. Nothing remains, General Lee, but to put your poor men on your poor mules and send them home in time for spring ploughing. This army is hopelessly whipped. They have already endured more than I thought flesh and blood could stand. The blood of every man who is killed from this time is on your head, General Lee.

Lee told Wise not to say such irresponsible things and reminded him of the heavy burdens he was already carrying as commander of the army. He then grew silent and said no more. Later, however, he would find that the mood of some of his other commanders had become even more pessimistic. Six of them held a private meeting at which they decided the army should be surrendered at once and, if they took the action, then Lee would be free of the burden and any blame. They sent General William Pendleton, Lee’s artillery chief, to see the commanding general and tell him of their plan. Lee exploded in anger, shouting his determination to fight on, saying, “I trust it has not come to that!”

However, on this same day, Lee encountered his nephew, George Taylor Lee, a cadet from the Virginia Military Institute who had served in the line at Richmond until the cadets were disbanded. Young George had elected to stay with the army, but had eventually left the column to visit his family in Powhatan County. Now, he had returned and when his uncle saw him, the elder Lee approached him with a tired and grave expression on his face. With distress in his voice, the general said, “My son, why did you come here?" George answered that he considered it his duty to return. Lee put his hand on his shoulder and, in a fatherly tone, told him, "You ought not to have come. You can't do any good here." Perhaps Lee’s resolve was beginning to crack as well.

As Union forces pressed in, Longstreet moved north across the river and Lee ordered his Commissary General to send all remaining undistributed rations west down the rail line towards Appomattox Station. As soon as Longstreet’s men were across, they burned the bridges behind them. However, it mattered very little as the quickly pursuing Federal cavalry soon found nearby fords and were again fast approaching the rear of the column. The river had, indeed, not proved to provide any protection and, to make matters worse, Lee soon learned that Gordon’s rear guard had failed to burn the High Bridge. As a result, Union infantry was now pouring across and closing in on Longstreet and Gordon’s troops near Cumberland Church. Once again, they were forced to turn and fight, but, this time, the pursuers did not seem to have any heart in the attack and were easily repulsed. Perhaps they too could see the end was near.

As Union forces pressed in, Longstreet moved north across the river and Lee ordered his Commissary General to send all remaining undistributed rations west down the rail line towards Appomattox Station. As soon as Longstreet’s men were across, they burned the bridges behind them. However, it mattered very little as the quickly pursuing Federal cavalry soon found nearby fords and were again fast approaching the rear of the column. The river had, indeed, not proved to provide any protection and, to make matters worse, Lee soon learned that Gordon’s rear guard had failed to burn the High Bridge. As a result, Union infantry was now pouring across and closing in on Longstreet and Gordon’s troops near Cumberland Church. Once again, they were forced to turn and fight, but, this time, the pursuers did not seem to have any heart in the attack and were easily repulsed. Perhaps they too could see the end was near.

Meanwhile, as his cavalry and infantry were sparring with Lee north of the river, Grant sent Sheridan on another race to the west. By 3:00 p.m., Sheridan and one of his cavalry divisions had reached Prince Edward Courthouse, where they learned of Lee’s rations that were bound for Appomattox Station. Sheridan sent word of this to Grant, who immediately ordered him to continue west and outrace Lee to the awaiting rations. When night fell, Grant entered Farmville and decided it was now time to see if he could convince Lee to surrender. He wrote a message down and handed it to his adjutant general, General Seth Williams. Williams carefully navigated his way towards Lee’s army under a flag of truce and finally delivered the message around 10:00 p.m.

Lee was having a late night conversation with Longstreet when the message arrived. He opened it and read Grant’s proposal:

HEADQUARTERS ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES,

April 7, 1865--5 p.m.

General R. E. LEE, Commanding C. S. Army:

GENERAL: The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C. S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

U. S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General, Commanding Armies of the United States

When he was done reading the message, Lee silently handed it to Longstreet who read it, then paused before handing it back, saying, “Not yet.” One of Lee’s staff, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Venable, suggested they ignore the proposal, but Lee said, “Ah, but it must be answered.” Lee then sat to write a reply, which was returned to General Williams for delivery to Grant. Williams did not reach Farmville until early the next morning. He handed Lee’s reply to General Grant, who immediately opened and read it.

APRIL 7, 1865.

Lieut. Gen. U.S. GRANT, Commanding Armies of the United States:

GENERAL: I have received your note of this date. Though not entertaining the opinion you express of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and therefore, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.

R. E. LEE, General

Lee was politely replying with an inquiry designed to buy more time. Before Williams had ridden a mile, Lee was already putting the army back on the road and heading west towards Appomattox Court House.

Saturday, April 8, 1865

As Lee’s men trudged on during the long night, exhaustion and depression began to take an increasingly heavy toll. Lee’s young former artillery chief, General Edward Porter Alexander, would later write of the agony of the final days of the march to Appomattox Court House.

The road was one sea of mud through which men, horses, ambulances, artillery, & cavalry splashed & floundered & stopped in the darkness & splashed & floundered & stopped again. And if it was that to me on horseback what must it have been to the poor fellows on foot loaded with muskets, blankets, & ammunition, & worn with continuous marching & digging & lack of food.

As the soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia moved continuously westward, they became more and more a mere ghost of the formidable and much feared fighting machine they once had been. Men can only be asked to endure so much and these men had been pushed beyond human limits. Lee was forced to use some of his limited cavalry resources to follow the main body, gathering up stragglers and moving them forward. However, this task was becoming increasingly difficult. One trooper wrote that he was horrified at the state of some of the men he encountered. These soldiers had “thrown away their arms and knapsacks [and were] lying prone on the ground along the roadside, too much exhausted to march further, and only waiting for the enemy to come and pick them up as prisoners.”

At first, the day’s march was assisted by the existence of two parallel roads. This allowed Lee to put Gordon’s men on the southernmost path, the Lynchburg Stage Road, while Longstreet’s soldiers moved on a plank road to the north. Unfortunately, these roads finally merged at a small village known as New Store, and progress ground to a halt as both columns became tangled and disorganized.

As for their Union pursuers, Grant had everyone in motion well before first light. The VI Corps left Farmville during the night, crossing over to the north side of the Appomattox River, while II Corps set out after Gordon’s column with vigor, quickly closing the distance between them. Sheridan’s cavalry, meanwhile, was once again off before dawn and moving fast. Sheridan divided his command into two elements with one under Merritt and the other under Crook. Crook’s command quickly headed west along the Southside Railroad, entering Pamplin Station around noon. There, they caught up with the trainload of rations Lee had sent west from Farmville towards Appomattox Station.

At the same time, Major Young’s scouts continued to pay dividends. One of them actually convinced Confederate railroad engineers to bring the supplies Lee expected to find at Lynchburg east to Appomattox Station. Upon hearing this, Sheridan realized that, if he could get there first, it might strike another crippling blow to Lee and his army. He continued west at an even quicker pace, with Ord’s Army of the James and Griffin’s V Corps following as fast as they could march.

At the same time, Major Young’s scouts continued to pay dividends. One of them actually convinced Confederate railroad engineers to bring the supplies Lee expected to find at Lynchburg east to Appomattox Station. Upon hearing this, Sheridan realized that, if he could get there first, it might strike another crippling blow to Lee and his army. He continued west at an even quicker pace, with Ord’s Army of the James and Griffin’s V Corps following as fast as they could march.

As the Union army set off, Grant received Lee’s reply of the previous night. He could see that Lee was skillfully avoiding the question of surrender, but he was convinced of the need to maintain their correspondence. Before he set out to follow his men, he sat down to write another letter to Lee.

APRIL 8, 1865

General R. E. LEE, Commanding C. S. Army:

GENERAL: Your note of last evening, in reply to mine of same date, asking the condition on which I will accept the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, is just received. In reply I would say that, peace being my great desire, there is but one condition I would insist upon, viz, that the men and officers surrendered shall be disqualified for taking up arms again against the Government of the united States until properly exchanged. I will meet you, or will designate officers to meet any officers you may name for the same purpose, at any point agreeable to you, for the purpose of arranging definitely the terms upon which the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia will be received.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

U.S. GRANT, Commanding Armies of the United States

With the new letter on its way, Grant set out, crossing the river and following II and VI Corps. The weather was sunny and pleasant, and the muddy roads finally were beginning to dry. However, the weather did not help Grant, who began to suffer terrible headaches. The pain became so excruciating that he could no longer ride. He stopped at a small house called “Clifton,” dismounted his horse, Cincinnati, and went inside where his surgeons tried applying remedies such as foot soaks and a wrist poultice. When these did not bring relief, he finally decided to try to sleep. Lying down in the only bed in the house, he napped fitfully as his army marched steadily westward after Lee.

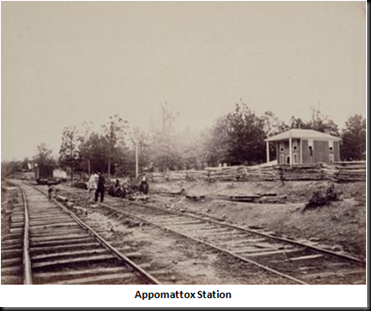

Late that afternoon, Sheridan’s cavalry, under the command of General Custer, galloped into Appomattox Station, which consisted of only a few houses, and discovered Lee’s supplies from Lynchburg waiting for them, with a squad of Confederate cavalry acting as guards. A private from the 2nd New York Cavalry rode up to an engineer, calling out “Hands up,” while leveling his carbine, and the four trains of rations were captured. Knowing a Confederate force of some unknown size was nearby, Custer called for any men with train engineering experience to come forward so they get the cars away. As the men rode about the trains shouting in celebration, artillery shells began to come crashing down on them.

The cannon fire was coming from Lee’s Reserve Artillery under the command of General Rueben Lindsay Walker. These guns had been sent ahead of Lee’s main column so that the caissons did not further slow the army’s pace. Walker had approximately 100 cannon, 200 baggage wagons, and the army hospital wagons all drawn up in a camp for the night with no preparation for action, as they did not think Sheridan’s troopers were so close. Suddenly, as Walker and his men were sitting down to eat their dinners, the cry went up, “Yankees! “Sheridan!”

Walker quickly deployed his guns in a semicircle, defended by a few engineers and a small cavalry brigade, and opened fire on Custer and his men. Custer sent skirmishers forward to develop Walker’s position and, as the sun began to set, he launched several piecemeal charges against the Confederate artillery. These were all turned back and the flamboyant Union cavalryman realized that sterner measures would be required. Around 8:30 p.m., he mounted an all-out assault that resulted in a brief, bitter fight. Eventually, Walker’s men fled, leaving 30 cannon and 1,000 men behind as prisoners. It was another loss Lee could ill afford.

Phil Sheridan arrived to meet with Custer just as the fighting was dying down. Assessing the situation, he jotted down a hurried note to Grant, urging the infantry forward at all speed, predicting that, if they could join him by morning, “we will perhaps finish the job…I do not think Lee will surrender unless he is compelled to do so.”

As night fell, Lee made his camp in a wooded area just east of Appomattox Court House along Rocky Run. With the setting of the sun, he and his men could now see the ominous glow of Federal campfires, ringing them on every side except to the north. As he rested from the day’s ride, Grant’s latest message came through the picket lines near Mahone’s division. Holding it near a candle, he read it in silence, then, after consulting none of his staff, he wrote a reply.

APRIL 8, 1865.

Lieutenant-General GRANT, Commanding Armies of the United States:

GENERAL: I received at a late hour your note of to-day. In mine of yesterday I did not intend to propose the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, but to ask the terms of your proposition. To be frank, I do not think the emergency has arisen to call for the surrender of this army; but as the restoration of peace should be the sole object of all, I desired to know whether your proposals would lead to that end. I cannot, therefore, meet you with a view to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia; but as far as your proposal may affect the C. S. forces under my command, and tend to the restoration of peace, I should be pleased to meet you at 10 a.m. to-morrow, on the old stage road to Richmond, between the picket-lines of the two armies.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

R. E. LEE, General

Lee gave his response to a courier to return to Grant’s messenger, and then called a council of war among his staff and key commanders. Sitting around a campfire on their blankets and saddles, Lee told his officers of the latest note from Grant and of his reply offering to meet the Union general in person. They began a discussion of what surrender might mean for them and for the South. Some of the officers believed that the army should be dispersed to the hills to fight a guerilla war, which Lee angrily dismissed. Finally, he issued his orders for the next day: The army would ignore the surrender proposal and attempt to break out beyond Appomattox Court House. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry would launch the attempted breakthrough and, once a route was opened, Gordon’s 4,000 infantry would hold it open as Longstreet’s men moved through, and then Gordon would follow. Lee was hoping that he only had Sheridan’s cavalry to contend with and not infantry, as well. When Gordon raised the issue that Union infantry might also soon arrive if they had not already, Lee hesitated, adding an addendum to Fitzhugh Lee’s orders: If he encountered Union infantry, Lee would have no choice except to “accede to the only alternative left us”—surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee’s response reached Grant at midnight. He read it silently, then handed it to his Chief of Staff, General John Rawlins. Rawlins, an outspoken man who had been with Grant since the beginning, read it out loud so the entire staff could hear it. Remembering that President Lincoln had ordered Grant to ensure he never conducted any negotiations with the enemy beyond those of a strictly military nature, Rawlins told Grant that he could not meet with Lee under the guise of peace talks. As was his habit, Rawlins was quite emotional and very direct in his speech and, as was his habit, Grant replied calmly, “We’ve got to make some allowance for the trying place Lee is in. He’s got to obey orders of his government. It all means the same thing, Rawlins. If I meet with Lee, he’ll surrender before I leave.”

Rawlins remained unconvinced but Grant had made up his mind. As the early minutes of April 9 ticked by, he sat down once again to compose a letter to Lee.

HEADQUARTERS ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES,

April 9, 1865

General R. E. LEE, Commanding C. S. Army:

GENERAL: Your note of yesterday is received. As I have no authority to treat on the subject of peace the meeting proposed for 10 a.m. to-day could lead to no good. I will state, however, general, that I am equally anxious for peace with yourself, and the whole North entertain the same feeling. The terms upon which peace Call be had are well understood. By the South laying down their arms they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of human lives, and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed. Sincerely hoping that all our difficulties may be settled without the loss of another life, I subscribe myself,

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

U.S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General, U.S. Army

Sunday, April 9, 1865

At 3:00 a.m., Gordon and Fitzhugh Lee’s men were assembled in line of battle in the fields surrounding Appomattox Court House. Gordon’s 4,000 men were on the left, Lee’s troopers on his right, and Longstreet’s 3,000 infantry behind them to the northeast, facing Humphrey’s and II Corps. Around them, uncounted thousands milled aimlessly, a disorganized mob of starving soldiers looking for food. At first, Fitzhugh Lee and Gordon argued about who should go in first. Gordon thought there was nothing but cavalry in front, therefore Lee should lead the attack and push through. But, as the cavalryman stared though his glasses, he was not convinced that Sheridan was alone, arguing that he believed there might be infantry in the woods and, therefore, Gordon’s men should step off first. Finally, one of Gordon’s officers, General Bryan Grimes, told both men that it was time someone attacked and that he would just go ahead and do it.

Grimes led the entire corps, or what was left of it, forward, quickly overrunning a roadblock of Union cavalry and artillery about one-quarter of a mile down the Lynchburg Stage Road. His men now pushed rapidly forward, encouraged by their initial success and they attacked and dispersed a second roadblock as Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry swung in from their right, attacking the enemy’s flank. Just as planned, the door to escape was open. However, no sooner had it opened than it closed once again.

Gordon and Lee’s men suddenly ran into swarms of infantry, just coming into the line across the road and into the fields beyond. At first, it was just Ord’s soldiers in their way, but within minutes, Griffin’s V Corps was also on the scene. Gordon’s men fought ferociously but could not gain any headway. Gordon sent General Lee an urgent message saying, “I’ve fought my corps to a frazzle, and I can do nothing unless Longstreet supports me.”

Gordon and Lee’s men suddenly ran into swarms of infantry, just coming into the line across the road and into the fields beyond. At first, it was just Ord’s soldiers in their way, but within minutes, Griffin’s V Corps was also on the scene. Gordon’s men fought ferociously but could not gain any headway. Gordon sent General Lee an urgent message saying, “I’ve fought my corps to a frazzle, and I can do nothing unless Longstreet supports me.”

Lieutenant Colonel Venable delivered the message to Lee at 8:30 a.m., but the army’s commander had been watching Gordon’s attack since first light and knew what was happening. Lee read the dispatch, thought for a moment, then said, “Then there is nothing left for me to do but go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.” Longstreet arrived on the scene and noted that Lee was dressed in his finest uniform, as if he already knew that he would be seeing Grant that day. Lee asked his trusted corps commander’s advice on whether to surrender. Longstreet replied with a question of his own, “Can the sacrifice of the army help the cause in other quarters?” Lee said no and Longstreet answered, “Then your situation speaks for itself.”

Lee pondered Longstreet’s words, and asked General Mahone for his opinion. Mahone was of the same mind, so Lee turned to Longstreet one last time and asked him point-blank if he should surrender the army. Longstreet silently nodded his head.

With that, Lee mounted his horse, Traveller, and rode northeast toward the spot he expected to find Grant. However, it was then that he received Grant’s note from the previous night in which the Union commander rejected any peace talks. Lee quickly dictated a new letter and signed it, then sent it back through Union lines.

With that, Lee mounted his horse, Traveller, and rode northeast toward the spot he expected to find Grant. However, it was then that he received Grant’s note from the previous night in which the Union commander rejected any peace talks. Lee quickly dictated a new letter and signed it, then sent it back through Union lines.

APRIL 9, 1865.

Lieut. Gen. U.S. GRANT, Commanding U.S. Armies:

GENERAL: I received your note of this morning on the picket-line, whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now request an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant.

R. E. LEE, General

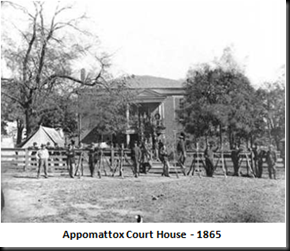

As he rode on, Lee could hear firing ahead and, as he was now anxious to have the killing stop, he sent a message to General Meade requesting an immediate truce along the line. Meade replied that he was not in communication with General Grant and had no authority to stop the attack, but would delay for one hour. In the meantime, he suggested that Lee send another note for General Grant through Sheridan’s lines. Lee did so, and ordered Gordon to place flags of truce all along his line.

As the two messages to Grant were going forward, the fighting came to a stop. Men on both sides who had been killing one another moments before, rested on their rifles and the fields around Appomattox Court House became eerily silent. As the firing subsided, the word of surrender began to spread and a Virginia cavalryman named W.L. Moffatt came upon a comrade who had been mortally wounded in the morning’s fighting. His dying friend looked up at him from where he lay on the ground, saying, “Moffett, it is hard to die now just as the war is over.”

Just before noon, Lee’s first message found General Grant as he was riding west of Walker’s Church. Still in great pain from his headache, Grant quickly scanned the message then handed it General Rawlins, who read it aloud. Recalling their argument of the previous night, Grant asked him, “Will that do, Rawlins?” His Chief of Staff smiled and replied, “I think that will do.” Grant stopped and drafted a reply to Lee.

Just before noon, Lee’s first message found General Grant as he was riding west of Walker’s Church. Still in great pain from his headache, Grant quickly scanned the message then handed it General Rawlins, who read it aloud. Recalling their argument of the previous night, Grant asked him, “Will that do, Rawlins?” His Chief of Staff smiled and replied, “I think that will do.” Grant stopped and drafted a reply to Lee.

HEADQUARTERS ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES

April 9, 1865

General R. E. LEE, Commanding C. S. Army:

Your note of this date is but this moment (11.50 a.m.) received. In consequence of my having passed from the Richmond and Lynchburg road to the Farmville and Lynchburg road I am at this writing about four miles west of Walker's Church, and will push forward to the front for the purpose of meeting you. Notice sent to me on this road where you wish the interview to take place will meet me.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

U. S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General

Grant handed the note to his adjutant general for delivery to General Lee, then set off at a gallop for Appomattox Court House. The pursuit was over and, soon, four hard years of death, destruction, pain, and suffering would be at an end.

Grant handed the note to his adjutant general for delivery to General Lee, then set off at a gallop for Appomattox Court House. The pursuit was over and, soon, four hard years of death, destruction, pain, and suffering would be at an end.

Grant suddenly noticed that his headache was gone.