Ask someone with a professed interest in the Civil War to characterize the conflict and you will often get the following summary: The South had better generals, won most of the battles, but lost the war when overwhelmed by Northern resources. As with any stereotypical view, this one contains elements of truth, but those bits of truth it contains are all thing that characterize the war in the East. There was another theater of war, however, and it was completely different from the war in the East. More importantly, it was here that the course of the war was truly determined. Yet, most Americans are either unaware of it or see it as a mere sideshow of the war. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Ask someone with a professed interest in the Civil War to characterize the conflict and you will often get the following summary: The South had better generals, won most of the battles, but lost the war when overwhelmed by Northern resources. As with any stereotypical view, this one contains elements of truth, but those bits of truth it contains are all thing that characterize the war in the East. There was another theater of war, however, and it was completely different from the war in the East. More importantly, it was here that the course of the war was truly determined. Yet, most Americans are either unaware of it or see it as a mere sideshow of the war. Nothing could be further from the truth.

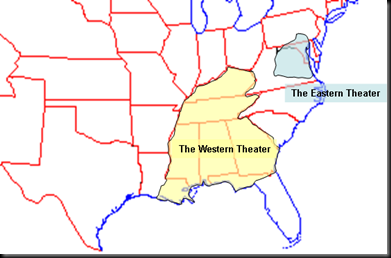

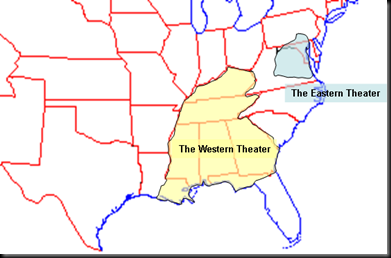

While the Civil War has long been seen as a conflict primarily fought and won in the small Eastern Theater of the war, specifically in the region encompassing Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, it can be argued that the war was truly determined in the West, in the vast theater between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. Here, Union and Confederate armies maneuvered over great distances and fought some of the most important battles and campaigns of the war. The Western Theater would also see a great deal of strategic innovation and it would produce some of Union’s finest commanders, those that would eventually bring victory to the Union cause. The South’s armies, meanwhile, would fight here with far fewer resources and, with a few exceptions, far less capable leadership than the Army of Northern Virginia. As a result, unlike that famous eastern army, the Confederate armies in the West would seldom see victory.

To understand the war in the West and why it was so different than that in the East, you must first understand the unique nature of the Western Theater in terms of geography and politics. Geographically, the theater can be characterized by its vastness, by the great distance armies would have to traverse in their operations. Unlike the Eastern Theater, which could be contained within an extremely small area bounded by the Shenandoah Valley, the Potomac River, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Rappahannock River, the Western Theater encompassed everything south of the Ohio River between the Appalachian Mountain and the Mississippi River. In realizing how difficult it would be for the North to take this region and for the South to defend the same area, one must realize that it took Napoleon eight years of campaigning to conquer an area of similar size in Europe.

To understand the war in the West and why it was so different than that in the East, you must first understand the unique nature of the Western Theater in terms of geography and politics. Geographically, the theater can be characterized by its vastness, by the great distance armies would have to traverse in their operations. Unlike the Eastern Theater, which could be contained within an extremely small area bounded by the Shenandoah Valley, the Potomac River, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Rappahannock River, the Western Theater encompassed everything south of the Ohio River between the Appalachian Mountain and the Mississippi River. In realizing how difficult it would be for the North to take this region and for the South to defend the same area, one must realize that it took Napoleon eight years of campaigning to conquer an area of similar size in Europe.

Unlike the East, where rivers generally flow west to east and acted as boundaries and barriers to strategic movement, in the West the critical waterways flowed north to south and, thus, became the invasion routes by which Federal armies moved. Therefore, their control became critical factors of the opposing sides’ strategies. In addition, because the theater was so vast, the railroads and transportation networks, in general, influenced the conduct and progress of the war. Unlike the Army of the Potomac, Northern forces in the West operated far from their Eastern industrial base and, as a result, logistics and the movement of men and supplies became vital parts of Union planning and strategy. In turn, those factors would influence Southern defensive efforts and make raiding lines of communication a vital component of Southern strategic thinking.

Here in the West, geography would influence the conduct of the war simply because the fighting here was so far from either side’s political centers in Washington and Richmond. This would tend to make the Southern effort a poor stepchild to the fighting in the East. Despite the fact that Jefferson Davis was from Mississippi, Southern forces would never receive the resources they required or the leadership they needed to counter the North’s armies. In terms of resources, while the centralized logistics organization in Richmond was responsible for supplying the western Confederate armies, special privileges were accorded the Army of Northern Virginia. For instance, while Confederate government purchasing agents combed the countryside buying up food and raw material to supply armies in both theaters, the Army of Northern Virginia was permitted to have its own purchasing agents, who bought from the same sources using the same funds as the government purchasing agents. Further, while food and other provisions bought in the East were generally earmarked for Lee’s army, these same supplies when found west of the Appalachians were fair game. It was, apparently, not uncommon for the government’s agents to be searching for provisions in a western state of the Confederacy and find themselves unable to procure any because the Army of Northern Virginia’s agents had bought everything up and shipped it east. Northern forces, however, would always receive more than adequate priority for supply and the excellent management of the Union’s rail system by the War Department ensured a steady flow of materiel.

As for leadership, Union commanders prospered in the West, acting well outside the limelight of the Eastern press and away from the prying eyes of Washington. Plus, Lincoln possessed a better understanding than Davis of the importance of the West, and gave successful commanders, such as Grant and Sherman, significant political support. At the same time, after the death of Albert Sidney Johnston at Shiloh, Southern commanders were nothing but inept.  Joe Johnston, while seemingly possessing the right qualifications for command, never could understand exactly how to lead forces spread across such a large region. As a result, he never took the initiative and was constantly seeking direction from Richmond. Braxton Bragg, meanwhile, was a disaster as a commander, and he and his generals constantly quarreled. Worse, when Bragg’s generals plotted against him and communicated directly with President Davis to obtain Bragg’s removal, Davis did little to quell the uprising and his inaction simply made things worse. As a result, there was never any command cohesion, a vital ingredient that no army can afford to be without.

Joe Johnston, while seemingly possessing the right qualifications for command, never could understand exactly how to lead forces spread across such a large region. As a result, he never took the initiative and was constantly seeking direction from Richmond. Braxton Bragg, meanwhile, was a disaster as a commander, and he and his generals constantly quarreled. Worse, when Bragg’s generals plotted against him and communicated directly with President Davis to obtain Bragg’s removal, Davis did little to quell the uprising and his inaction simply made things worse. As a result, there was never any command cohesion, a vital ingredient that no army can afford to be without.

Now armed with a brief baseline of geography, resources, and leadership, let’s examine the chronology of the war in the West with its key events and trends. First, 1861 was as a time of relative quiet in this theater, where both sides maneuvered politically in the border states, took up their positions, and built their fledgling armies. During this period, the commanders on the Northern side were a primarily a collection of politically appointed men with varying degrees of military experience. The South would see some of same phenomenon and neither side would undertake any truly major military operations.

Now armed with a brief baseline of geography, resources, and leadership, let’s examine the chronology of the war in the West with its key events and trends. First, 1861 was as a time of relative quiet in this theater, where both sides maneuvered politically in the border states, took up their positions, and built their fledgling armies. During this period, the commanders on the Northern side were a primarily a collection of politically appointed men with varying degrees of military experience. The South would see some of same phenomenon and neither side would undertake any truly major military operations.

However, as 1862 began, changes had taken place and movement had begun. During this year, the entire pattern for the war in the theater would be established. New federal commanders were in place, men like Halleck, Buell, Rosecrans, and an obscure Illinois general named Grant. The year began with a pair of major Union victories led by the latter at Forts Henry and Donelson. These twin victories not only provided the Northern people a much needed hero, they provided the North a psychological edge in the West which it virtually never surrendered. Unlike the East, the first major victory here went to the North and the effect of that cannot be underestimated. Here, there was no aura of Southern invincibility and no sense of Northern despair. Plus, this brief campaign, with its novel joint Army-Navy operations, began a process of innovation in strategy that would eventually determine the war’s outcome. The victories at Henry and Donelson resulted in the capture of Nashville, the withdrawal of Confederate forces from Tennessee, and effective Northern control of that critical state.

However, as 1862 began, changes had taken place and movement had begun. During this year, the entire pattern for the war in the theater would be established. New federal commanders were in place, men like Halleck, Buell, Rosecrans, and an obscure Illinois general named Grant. The year began with a pair of major Union victories led by the latter at Forts Henry and Donelson. These twin victories not only provided the Northern people a much needed hero, they provided the North a psychological edge in the West which it virtually never surrendered. Unlike the East, the first major victory here went to the North and the effect of that cannot be underestimated. Here, there was no aura of Southern invincibility and no sense of Northern despair. Plus, this brief campaign, with its novel joint Army-Navy operations, began a process of innovation in strategy that would eventually determine the war’s outcome. The victories at Henry and Donelson resulted in the capture of Nashville, the withdrawal of Confederate forces from Tennessee, and effective Northern control of that critical state.

Next, Grant would move forward to his campaign southward to Shiloh, where a violent and critical April battle made a great impact on the course of the war. From it, Grant learned not to underestimate his opponent and that the South must be defeated by force of arms if the Union was to be restored, while the South would lose its most able commander in the West, Albert Sidney Johnston. Perhaps more importantly, however, more men would die on a single field of battle than had been lost in all of America’s wars up to that time. Thus, the American people would see for the first time the potential price of the war in human loss and suffering.

Next, Grant would move forward to his campaign southward to Shiloh, where a violent and critical April battle made a great impact on the course of the war. From it, Grant learned not to underestimate his opponent and that the South must be defeated by force of arms if the Union was to be restored, while the South would lose its most able commander in the West, Albert Sidney Johnston. Perhaps more importantly, however, more men would die on a single field of battle than had been lost in all of America’s wars up to that time. Thus, the American people would see for the first time the potential price of the war in human loss and suffering.

Of course, Grant took a beating in the press for Shiloh even though he had turned a near disaster into a signal victory. The press and some politicians could only see the “near disaster” part of the equation. As a result, Grant would briefly be relegated to an administrative position, so to speak, and, with Henry Halleck in charge, Union forces failed to exploit the victory at Shiloh, making a slow, painful advance to Corinth. But soon enough, Halleck would move east and progress would be made. Union forces seized New Orleans, and that was followed by the preliminary moves of the Vicksburg campaign and the great Union effort to secure control of the Mississippi. Finally, 1862 ended with the South’s offensive in Kentucky to Perryville, and the bloody New Year’s standoff at Stone’s River, both of which serve as examples of how their ineffective command leadership and internal command politics could turn potential victory into ultimate defeat.

The next year, 1863, was a monumental one in the West and in course of the war. During 1863, Grant rose as a commander and his historic partnership with Sherman took shape. In addition, the career of Rosecrans reached its zenith before disappearing forever, while the considerable command talents of George Thomas emerged. On the Southern command front, Joe Johnston’s painful efforts to command an entire theater, the meager efforts of Pemberton to counter Grant in Mississippi, and the snake pit that was the command staff in Bragg’s Army of Tennessee all acted to doom any chance of Southern success. All these were critical factors in the eventual campaigns of this important year.

Any examination of 1863 in the West must revolve around Grant’s brilliant campaign against Vicksburg. Grant’s innovative use of naval forces and the spirit of partnership he and Sherman created in working with Admiral Porter led to the successful running of the gauntlet created by Vicksburg’s guns on the Mississippi, which, in turn, allowed Grant to gain a foothold on the high, dry ground south of the city. Grant maneuvered his forces quickly to cut off Vicksburg’s garrison and block Confederate relief forces, baffling both Pemberton and Johnston in the process. Once the city’s garrison was bottled up inside their defenses surrounding Vicksburg, it was all a matter of time—time ran out on July 4, with the surrender of the city and its 30,000 defenders. Then, the weight of the campaigning moved back to Tennessee, where, after considerable pressure from Lincoln, Rosecrans finally moved to take Chattanooga and its vital position astride the South’s east-west rail lines. However, “Old Rosy,” as his soldiers called him affectionately, was sent reeling back to that city after his stunning defeat by Bragg at Chickamauga, the Confederacy’s only major victory in the West.

Any examination of 1863 in the West must revolve around Grant’s brilliant campaign against Vicksburg. Grant’s innovative use of naval forces and the spirit of partnership he and Sherman created in working with Admiral Porter led to the successful running of the gauntlet created by Vicksburg’s guns on the Mississippi, which, in turn, allowed Grant to gain a foothold on the high, dry ground south of the city. Grant maneuvered his forces quickly to cut off Vicksburg’s garrison and block Confederate relief forces, baffling both Pemberton and Johnston in the process. Once the city’s garrison was bottled up inside their defenses surrounding Vicksburg, it was all a matter of time—time ran out on July 4, with the surrender of the city and its 30,000 defenders. Then, the weight of the campaigning moved back to Tennessee, where, after considerable pressure from Lincoln, Rosecrans finally moved to take Chattanooga and its vital position astride the South’s east-west rail lines. However, “Old Rosy,” as his soldiers called him affectionately, was sent reeling back to that city after his stunning defeat by Bragg at Chickamauga, the Confederacy’s only major victory in the West.  Unfortunately for the South, Bragg did not effectively follow-up on that victory by engaging and destroying Rosecrans’ army. Rather, he elected to lay siege to Rosecrans and Chattanooga, surrendering the precious and vital initiative Chickamauga provided. This action also allowed the bickering and back-stabbing by his generals to reach new heights, creating a toxic political environment around Bragg that adversely impacted his decision-making and opened the door for an eventual Union breakout from Chattanooga.

Unfortunately for the South, Bragg did not effectively follow-up on that victory by engaging and destroying Rosecrans’ army. Rather, he elected to lay siege to Rosecrans and Chattanooga, surrendering the precious and vital initiative Chickamauga provided. This action also allowed the bickering and back-stabbing by his generals to reach new heights, creating a toxic political environment around Bragg that adversely impacted his decision-making and opened the door for an eventual Union breakout from Chattanooga.

That breakout was engineered by Grant, who was appointed to overall command in the West. Grant went immediately to Chattanooga, took action to resupply the garrison, invigorated Union forces with confidence, and executed a campaign that freed it from the Confederate siege. Bragg and his army were sent reeling south into Georgia and, as 1863 came to a close, the South was truly split in two, the door to the Deep South was open, and the road to the vital city of Atlanta lay ahead. With that, the foundation for the eventual Union victory had been laid.

In the early spring of 1864, Grant departed the theater to assume command of the U.S. Army and undertake the overall direction of the Union’s war efforts. But, the importance of the West in the war did not diminish. As a part of Grant’s strategy to simultaneously engage the Confederate armies across all fronts, Sherman moved against Atlanta, Joe Johnston, and the Army of Tennessee. While Johnston effectively fought a war of delay against Sherman’s campaign of maneuver, his strategy to trade ground for time angered Jefferson Davis. Johnston was dismissed and replaced by the aggressive John Bell Hood. Rather than meet Sherman’s maneuvering with defensive stands, Hood took the offensive attacked Sherman’s army. In the end, Hood’s approach did not forestall Sherman’s capture of Atlanta any longer than Johnston might have. However, in the process, unlike Johnston, Hood bled the Army of Tennessee, losing men and resources which could not be replaced.

In the early spring of 1864, Grant departed the theater to assume command of the U.S. Army and undertake the overall direction of the Union’s war efforts. But, the importance of the West in the war did not diminish. As a part of Grant’s strategy to simultaneously engage the Confederate armies across all fronts, Sherman moved against Atlanta, Joe Johnston, and the Army of Tennessee. While Johnston effectively fought a war of delay against Sherman’s campaign of maneuver, his strategy to trade ground for time angered Jefferson Davis. Johnston was dismissed and replaced by the aggressive John Bell Hood. Rather than meet Sherman’s maneuvering with defensive stands, Hood took the offensive attacked Sherman’s army. In the end, Hood’s approach did not forestall Sherman’s capture of Atlanta any longer than Johnston might have. However, in the process, unlike Johnston, Hood bled the Army of Tennessee, losing men and resources which could not be replaced.

With Atlanta in Union hands, Lincoln’s reelection was almost assured and Sherman was poised for his great raid to the Atlantic. Rather than trying to stop him directly from his march to Savannah, Hood elected to move against Sherman’s rear with an ill-fated invasion of Tennessee. By threatening Sherman’s lines of communication, Hood hoped to stop Sherman from moving deeper into the South. However, like Grant in Mississippi, Sherman was not concerned about his rear, as his army marched to Savannah by living off the land. Meanwhile, Union forces under George Thomas proved more than sufficient to first bloody Hood at the Battle of Franklin, and  then nearly destroy the Army of Tennessee outside Nashville. With that, Hood and what was left of his army retreated and faded away, no longer an effective fighting force. Joe Johnston once again took command of that army and, as Sherman devastated South Carolina and steadily moved north to join with Grant, he tried desperately to link up with Lee’s army for a final climatic battle that was not to be. Lee surrendered at Appomattox and Johnston did the same shortly thereafter, capitulating to Sherman in North Carolina.

then nearly destroy the Army of Tennessee outside Nashville. With that, Hood and what was left of his army retreated and faded away, no longer an effective fighting force. Joe Johnston once again took command of that army and, as Sherman devastated South Carolina and steadily moved north to join with Grant, he tried desperately to link up with Lee’s army for a final climatic battle that was not to be. Lee surrendered at Appomattox and Johnston did the same shortly thereafter, capitulating to Sherman in North Carolina.

The war in the West was truly a watershed and one of an entirely different character than that fought in the East. Here, maneuver, rapid movement over great distance, joint operations, strategic raiding, and “hard war” were the hallmarks, as opposed to the set-piece battles and stalemate that characterized the East. In the West, Southern armies were repeatedly battered and defeated on almost every occasion, while the North moved steadily deeper and deeper into the Confederacy. So, while Lee held the line in Virginia, the rest of the Confederacy was lost. As a result, the outcome of the war was truly determined far from the fields of Virginia.

No comments:

Post a Comment