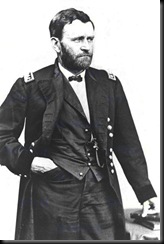

At about nine o’clock on the evening of March 8, 1864, a man dressed modestly in the blue uniform of the U.S. Army casually walked from the Willard Hotel up Pennsylvania Avenue toward the White House. Those who walked by the officer probably took little note of him, given his undistinguished appearance. He was of average height with a neatly trimmed beard, thoughtful eyes of dark gray, and an expression that often indicated deep concentration but gave little, if any, hint as to his thoughts. Further, he did not carry himself as one would have expected a military man. Rather than an erect stance, with shoulders thrust back, and a walk that emulated the rhythmic step of a march, he sauntered at his own pace, somewhat stooped, with his shoulders held as casually as any civilian on a Sunday stroll. In addition, as this was Washington D.C., even the epaulets of a Major General he carried on his shoulders likely garnered little attention. But, this was a man everyone in Washington, especially those attending the reception up the street at the White House, was waiting to meet. His name was Ulysses S. Grant.

Lincoln then turned and introduced Grant to his Secretary of State, William Seward, and to Mrs. Lincoln. All the while, the excited crowd in the Blue Room pressed nearer, everyone wanting a closer look at Grant, and became almost unmanageable. In response, Seward took the general by the hand through the crowd to the East Room where there was more room, but the crowd only became more excited, surging forward, swaying, and chanting, “Grant! Grant! Grant!” Finally, Steward convinced the usually reticent and reserved Grant to stand on a sofa so that all could see him. This seemed to excite the throng even more and they moved forward in often vain attempts to shake the general’s hand. It would be an hour before they would calm down enough to allow Grant to retire to a drawing room in order to meet privately with the president and the Secretary of War, Edward Stanton.

The crowd’s excitement was not surprising. This, after all, was the man many saw as the potential savior of the nation’s military fortunes, the man who had never been beaten, the man from the West who had come to Washington to lead all their armies to victory over the rebellious states of the Southern Confederacy, and the man who would finally end the horrific bloodshed that had now lasted for three long years. However, while they clearly recognized the importance of the moment, they did not truly perceive the magnitude of what happened on this March evening.

This was the culmination of a long process. It was the end of a search, a quest, even, by the president to find a commander who would not only fight and win, but who also had the strategic vision, as well as the political acumen, to effectively command all the nation’s armies. The former had been proven repeatedly by Grant, but the latter would only be demonstrated with time. Grant would first have to develop a strategy to achieve Lincoln’s war aim to reunify the nation on the president’s terms, which meant the complete political and military defeat of the Confederate States of America. Then, Grant would have to accomplish the more daunting task of successfully executing that strategy to its ultimate conclusion.

To place Grant in position to accomplish these tasks, Lincoln and the Congress had crafted and passed a bill which restored the grade of lieutenant general, a rank previously held only by George Washington. The bill was signed into law on February 26, 1864, Grant was nominated to the Senate on March 1, confirmed by that body on March 2, and ordered to Washington the next day. He would receive the commission from President Lincoln on March 9, the morning after the reception at the White House, in the presence of the Cabinet, Grant’s eldest son, Fred, and a few members of the general’s staff. Grant described the presentation later in his memoirs:

The President in presenting my commission read from a paper --stating, however, as a preliminary, and prior to the delivery of it, that he had drawn that up on paper, knowing my disinclination to speak in public, and handed me a copy in advance so that I might prepare a few lines in reply. The President said: "General Grant, the nation's appreciation of what you have done, and its reliance upon you for what remains to be done in the existing great struggle, are now presented, with this commission constituting you lieutenant-general in the Army of the United States. With this high honor, devolves upon you, also, a corresponding responsibility. As the country herein trusts you, so, under God, it will sustain you. I scarcely need to add, that, with what I here speak for the nation, goes my own hearty personal concurrence."

As was his way, Grant listened intently, then rose to provide a humble, succinct, concise reply, stating, “Mr. President, I accept the commission, with gratitude for the high honor conferred. With the aid of the noble armies that have fought in so many fields for our common country, it will be my earnest endeavor not to disappoint your expectations. I feel the full weight of the responsibilities now devolving on me; and I know that if they are met, it will be due to those armies, and above all, to the favor of that Providence which leads both nations and men.” With that, Mr. Lincoln’s new general set out to accomplish the president’s goals.

No path to these momentous meetings at the White House could have been more arduous or unpredictable as that taken by Ulysses S. Grant. Grant had begun his military career as a young West Point cadet from Ohio. His father, Jesse Grant, had obtained the appointment from Ohio congressman Thomas Hamer, over young Ulysses’ quiet objection. Grant had not been a particularly conscientious student while growing up and the small Ohio community of Georgetown in which he was raised had limited facilities for education. In Grant’s own words, the schools in the town were “very indifferent.” As a result, upon entry to the U.S. Military Academy in 1839, he lacked the depth of academic knowledge and skills required of a future military engineer, especially in mathematics. As to the latter, Grant would write in his memoirs that he had never even seen a book on mathematics higher than simple arithmetic, much less algebra, until he was appointed to West Point.

While there, he met and courted Julia Dent, the sister of a West Point classmate. Grant fell deeply in love with Julia and proposed to her, despite her father’s objections that a poor lieutenant was unsuitable for his daughter. Before they could marry, however, war with Mexico broke out and Grant was deployed to the theater of war along with his regiment. Despite the fact that he was assigned as a quartermaster, young Lieutenant Grant would see a significant amount of combat. He proved himself to be resourceful and very brave under fire, receiving a brevet promotion to first lieutenant.

With the end of the war in Mexico, Ulysses Grant would return to the life of the peacetime army officer. He married Julia and they enjoyed the next four years in domestic bliss. Soon, however, all would change. Grant received orders to go west to the Oregon Territory. He wisely decided that the journey to the Pacific coast, which required a crossing of the Isthmus of Panama, would be too difficult for Julia, who was now pregnant with their second child, and his son Fred, who was barely two years old. They would stay in St. Louis with Julia’s family and Grant would go alone to Oregon. The two years absence for the dedicated husband and father that followed proved to be Grant’s undoing. The combination of intense loneliness and the dreary boredom of frontier garrison life were too much for him. He was promoted to captain but, in the old peacetime army, there were no prospects for advancement beyond that grade. Rumors began that he had turned to alcohol to combat his growing depression, and these rumors would follow him the rest of his life.

Finally, Grant could take it no longer. He had tried without success to raise the money needed to bring his small family west, and could no longer see any attraction in the military life. So, in March 1854, Ulysses Grant resigned his commission and headed for Missouri, telling his comrades, ““Whoever hears of me in ten years will hear of a well-to-do old Missouri farmer.”

With the firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for volunteers, Grant found new life and he embraced this opportunity with the tremendous energy that would characterize the remainder of his military career. He was soon placed in the employ of the governor of Illinois, helping him to raise and organize volunteer regiments. Within a few weeks, in May 1861, he wrote to the Adjutant General in the War Department requesting command of a regiment and the rank of colonel. This might seem a somewhat bold act for a previously failed captain, but Grant later wrote, “I felt some hesitation in suggesting rank as high as the colonelcy of a regiment, feeling somewhat doubtful whether I would be equal to the position. But I had seen nearly every colonel who had been mustered in from the State of Illinois, and some from Indiana, and felt that if they could command a regiment properly, and with credit, I could also.”

Grant would never receive a reply to his request and a trip to Cincinnati to gain an audience with General McClellan failed to produce results. In the meantime, however, the governor of Illinois appointed him to command of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, with the rank of Colonel of Volunteers. Grant immediately demonstrated a real gift for organization and a unique understanding of the volunteer soldier, quickly whipping his unit into shape via a combination of benevolent leadership and army discipline. His first opportunity to take command in battle arrived shortly thereafter when he received orders to move to the relief of another Illinois regiment surrounded by Confederate troops near Palmyra, Missouri. His regiment quickly broke camp and moved into Missouri. As they approached the position of the Confederate forces, Grant began to feel tremendous anxiety.

As we approached the brow of the hill from which it was expected we could see Harris' camp, and possibly find his men ready formed to meet us, my heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on. When we reached a point from which the valley below was in full view I halted. The place where Harris had been encamped a few days before was still there and the marks of a recent encampment were plainly visible, but the troops were gone. My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him. This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards. From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy, though I always felt more or less anxiety. I never forgot that he had as much reason to fear my forces as I had his. The lesson was valuable.

With that lesson, Grant would demonstrate another key characteristic of his rise to command—the ability to learn from experience. From that point forward, he would always learn from his mistakes as well as his successes. Shortly thereafter, Grant was promoted to brigadier general and selected by the commander of the Western Department, General John C. Fremont, to take command of the Military District of Southeastern Missouri, with headquarters in Cairo, Illinois. Fremont later said that he selected Grant because he possessed "the soldierly qualities of self-poise, modesty, decision, attention to details." Whatever the reason, Grant’s rise to command had begun.

As Grant’s elevation continued and he learned and grew as a commander, his leadership style and command process began to take shape. Some elements of his command “portfolio” were engrained early in his wartime career and became basic parts of the foundation for his style of leadership and command. Many of these would prove to be constant sources of strength, but, as would be seen later in the 1864 Overland Campaign, a few would prove to be liabilities as his scope of command widened and became more complex.

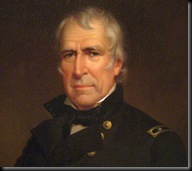

The first of these command “constants” was Grant’s need to command based on what he “saw” rather than on the reports of his staff. This was manifested in Grant’s tendency to command with what we might refer to today as a “hands-on” approach. Naturally, when serving as a regiment commander, Grant was always on the scene and controlling his troops. However, as he rose in command, he continued to exercise direct tactical control whenever he perceived the need to do so. Further, he also borrowed from Taylor a complementary trait of issuing orders and executing plans based upon the need “to meet the emergency” and not based upon the later views of history or, as it turned out, the specific instructions in his orders from superiors. Grant would seemingly always move and move quickly based upon the exigencies presented to him by the tactical and strategic situation as he saw it.

For example, in late 1861 and early 1862, Grant proposed to his department commander, General Henry Halleck, that he move to seize Confederate Forts Henry and Donelson, which commanded the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, respectively. After an initial rebuff, Halleck finally assented to the plan but only the part regarding Fort Henry. With typical energy and aggression, Grant quickly assembled a force of infantry and coordinated naval operations with Flag-Officer Foote, whose gunboats would be a necessary element of the campaign.

On February 6, 1862, his force rapidly subdued Fort Henry, whose poor placement along the river had led to most of the fort being flooded by the high waters of the Tennessee. Grant immediately informed Halleck of his success and told the department commander that he was moving forward to Fort Donelson. Grant presented this movement to Fort Donelson as fact and not as a proposal. While this might be seen as grandstanding by Grant, that was not the case. To Grant, the military situation dictated he move now and seize Donelson, which was a mere eleven miles away. He figured that if he could see Donelson’s importance, surely the Confederates could. With Fort Henry lost to them, Fort Donelson would be even more critical. Therefore, Grant needed to take Donelson before reinforcements reached the garrison.

Halleck responded to Grant that he was gathering reinforcements and would forward them as quickly as possible, but said nothing approving or disapproving Grant’s move to Fort Donelson. However, Grant inferred from Halleck’s dispatch regarding reinforcements that his superior wanted him to wait and consolidate with these new forces before attacking Fort Donelson. But, to Grant, “15,000 men on the 8th [of February] would be more effective than 50,000 a month later.” He, therefore, ordered Foote to move his gunboats to the Cumberland River and prepared to take Fort Donelson. Two days later, when he was in front of that fort, he would finally receive instructions from the plodding Halleck to dig in at Fort Henry and await reinforcements. Given the immediate situation, Grant wisely chose to ignore those orders as irrelevant.

I turned to Colonel J. D. Webster, of my staff, who was with me, and said: "Some of our men are pretty badly demoralized, but the enemy must be more so, for he has attempted to force his way out, but has fallen back: the one who attacks first now will be victorious and the enemy will have to be in a hurry if he gets ahead of me." I determined to make the assault at once on our left. It was clear to my mind that the enemy had started to march out with his entire force, except a few pickets, and if our attack could be made on the left before the enemy could redistribute his forces along the line, we would find but little opposition except from the intervening abatis. I directed Colonel Webster to ride with me and call out to the men as we passed: "Fill your cartridge-boxes, quick, and get into line; the enemy is trying to escape and he must not be permitted to do so." This acted like a charm. The men only wanted some one to give them a command.

However, at Fort Donelson, Grant was commanding a small army of only 15,000 men. By April, he would find himself commanding an army of 45,000 men at the Battle of Shiloh. Grant probably realized that practicality dictated he could no longer ride the lines and exercise such direct, tactical control. Rather, he must now leave that job where it properly belonged, with the regiment, brigade, and division commanders. Nevertheless, as demonstrated at Shiloh, Grant would remain a general who would command “on the scene.” He might not tactically direct the troops himself, but he would still ride up and down the line, conferring closely with his corps and division commanders, assessing the situation at various points for himself.

During this period of the war, Grant also demonstrated a style of command in which he applied his personal attention based upon his sense as to which sectors of the battle demanded his presence. That “sense” seems to have been based upon either the severity of the tactical situation, the sector’s overall tactical importance, or the capabilities of the particular corps or division commander engaged. This would become a hallmark of his leadership style, particularly the latter. Once Grant felt he could trust the judgment and capabilities of a commander, he would confer with him more and direct him less. For instance, Grant quickly ascertained that William T. Sherman, who would be come perhaps his closest friend and a virtual command partner, needed little direction in combat. Grant quickly came to trust Sherman’s assessments of his command’s situation, and merely provide him direction at the highest level. He later wrote of Sherman at Shiloh that,

During the whole of Sunday I was continuously engaged in passing from one part of the field to another, giving directions to division commanders. In thus moving along the line, however, I never deemed it important to stay long with Sherman. Although his troops were then under fire for the first time, their commander, by his constant presence with them, inspired a confidence in officers and men that enabled them to render services on that bloody battle-field worthy of the best of veterans.

However, other officers whom Grant trusted less would find themselves the subject of more regular scrutiny and more detailed direction. As would be seen, this formula would continue to be applied, even as Grant’s scope of command broadened.

With the size of his armies as well as the physical dimensions of the battlefield increasing, Grant naturally found that, while he might ride the lines and deliver orders orally in person, he must also use members of his staff to deliver orders. However, it was at Shiloh that he also discovered the importance of providing written direction when delivering his orders through a staff officer. During the first day of the battle, as Confederate forces were pushing Grant’s army back toward the banks of the Tennessee, he issued orders to General Lew Wallace urging him to bring his division forward at all possible speed from its position some six miles away. The first orders were sent via Captain Baxter, a quartermaster on Grant’s staff. Grant’s recollection was that he told Baxter to inform General Wallace to march immediately to Pittsburg Landing via the road “nearest the river.” Baxter made a memorandum of the order and dashed off to find Wallace.

Wallace received the order via Captain Baxter at approximately 11:30 a.m. He recorded in his official report that the order he received told him to “come up and take position on the right of the army and form my line of battle at a right angle with the river.” Wallace went on to write that he then selected “a road that led directly to the right of the lines as they were established around Pittsburg Landing on Sunday morning” and set off immediately. Grant wrote in his memoirs that, by 1:00 p.m., he had heard nothing from Wallace and decided to send two more staff officers, Colonel McPherson and Captain Rowley, to hurry him forward. Grant wrote that they returned to tell him that Wallace was marching by a circuitous route that had taken his command further away from Pittsburgh Landing and, as a result, his badly needed division would not arrive in time to participate in the day’s fighting.

Wallace, however, recorded that Rowley told him that “our lines had been beaten back; that the right, to which I was proceeding, was then fighting close to the river, and that the road pursued would take me in the enemy's rear, where, in the unfortunate condition of the battle, my command was in danger of being entirely cut off.” Rowley, Wallace wrote, then directed him to the correct and closer route. Unfortunately, because the original orders were incorrectly communicated, Wallace would have to countermarch and would not arrive until 1:00 a.m. the following morning.

Grant added in his memoirs that he “never could see and do not now see why any order was necessary further than to direct him to come to Pittsburg landing, without specifying by what route.” However, it is interesting to note that, from this point forward, whenever a member of Grant’s staff delivered orders, they were virtually always provided in writing and that Grant, himself, was usually the author. Further, these written orders were consistently so clear and concise that they might be considered models of command communications. Horace Porter, who first met Grant at Chattanooga in 1863 and later would join his staff, later wrote about Grant’s process for writing dispatches and the general’s distinctive mental process that surely contributed to their clarity.

At this time, as throughout his later career, he wrote nearly all his documents with his own hand, and seldom dictated to any one even the most unimportant despatch. His work was performed swiftly and uninterruptedly, but without any marked display of nervous energy. His thoughts flowed as freely from his mind as the ink from his pen; he was never at a loss for an expression, and seldom interlined a word or made a material correction. He sat with his head bent low over the table, and when he had occasion to step to another table or desk to get a paper he wanted, he would glide rapidly across the room without straightening himself, and return to his seat with his body still bent over at about the same angle at which he had been sitting when he left his chair.

Following the victory at Shiloh, Grant was harshly criticized in some western newspapers, particularly the Cincinnati Gazette. While he would profess some irritation and a desire to defend himself publicly in letters to Julia, he would never take a public action to counter them. The closest he would come to countering them was to send a letter to his loyal supporter, Congressman Elihu Washburne of Illinois, expressing his concern, stating, “To say that I have not been distressed at these attacks upon me would be false, for I have a father, mother, wife & children who read them and are distressed by them and I necessarily share with them in it.” While Grant probably hoped that the letter would spur Washburne to continue his public support, Grant never directly requested any assistance.

From the adulation he received after his victories at Forts Henry and Donelson and the sometimes outrageous attacks on him following Shiloh, Grant learned how fickle the fourth estate could be. As a result, for the remainder of the war, he would tend to ignore what the papers said about him, whether it was good or bad. However, Grant also assumed no one else around him cared about what the press was saying either. This might seem odd because, on the one hand, he was very aware how much certain aspects of press coverage, such as revealing specifics of planned operations, irritated some of his generals, particularly Sherman. Sherman detested reporters and, on several occasions, Grant had to step in to either sooth Sherman’s anger, coax him to soften his rhetoric towards the press, or actually defend his good friend and trusted ally. The latter went so far on one occasion that Grant expelled Thomas Knox, a reporter from the New York Herald, from his department because his reporting had so deeply offended Sherman.

However, at the same time, Grant seemed almost completely blind to how reports in the papers praising one general or criticizing another could influence relations between officers in his command. If he was not blind to it, he certainly gave it little priority. This may have been because, as was his tendency in dealing with people, Grant projected his own attitude onto others, particularly his subordinates. In other words, because he was not worried about the papers and, therefore, not sensitive to either their praise or criticism, it did not occur to him that others around him might be. As a result, he would become somewhat unaware of the corrosive effects publicity could have on the relationships among other officers and, hence, upon his own chain of command.

From Shiloh, Grant would move on to what was, perhaps, his greatest challenge as a commander, the Vicksburg campaign. Here, his greatest command traits would be ably demonstrated. His common sense approach to strategy along with his determination, tenacity, and remarkable analytical abilities came to the forefront. From Sherman’s disastrous frontal assault at Chickasaw Bluffs, he learned a direct attack on the city of Vicksburg was not feasible. Analyzing the terrain around the city, he determined that he must get his forces south of the city and set about finding away. Throughout the winter of 1862-1863, he has his men digging canals in what would be fruitless attempts to bypass the city west of the Mississippi. All the while, however, he was probing, planning, and scrutinizing the situation.

During this signal campaign, one can also see the effects of Grant’s interpersonal skills on his operations. Grant’s judgment of men was often based upon a quickly formed opinion. Once he took the measure of a man, he seldom changed his mind, no matter the evidence to the contrary. As a result, he formed strong bonds of personal and professional friendship with those he admired, and he was always loyal to those officers who he placed in this group. However, those who did not pass muster with him for either issues of character or professional abilities were tolerated only as long as required and were watched closely.

Therefore, Grant maintained a delicate balance, waving off the complaints against McClernand from Sherman and others, while watching the political general closely lest he finally step over the line farther than Grant could tolerate. McClernand came perilously close when he falsely reported seizing two of the forts guarding Vicksburg. This apparently convinced Grant to relieve McClernand, but Grant decided to wait until after Vicksburg had fallen before asking McClernand to take a leave of absence. However, McClernand did not make it that far. On June 17, Grant received a letter from Sherman complaining about a congratulatory address McClernand had made to his corps that made its way into the press, probably through McClernand’s efforts. Both Sherman and General McPherson complained that the address “did great injustice to the other troops engaged in the campaign.” As Grant had not approved its publication, this violated his standing policies on such matters. Grant had finally had enough and, on June 18, Grant relieved the troublesome politician-turned general. This episode also showed that Grant could act with political shrewdness and handle some delicate command personalities with deftness. He carefully tolerated McClernand, watched him closely, and then did not relieve him until after he gathered evidence and garnered sufficient support to do so.

Another key factor in Grant’s command process and style, and one that would become a key ingredient in his command during the eventual campaign against Lee, was his staff. As with many of the other elements of his command style, Grant’s use of his staff and the very men he selected for these positions, changed as he gained experience. When first promoted to brigadier general, he stuck with what he knew and his selections for staff reflected his inexperience. The positions were, naturally, those that reflected a traditional functional and administrative character, such as chief of staff, provost marshal, chief engineer, adjutant general, and quartermaster, as well as personal aides-de-camp.

At first, Grant chose men with whom he had some connection. This could be either professional or, in at least one case, geographic. For instance, upon promotion to brigadier general, he chose one officer from his old regiment, Lieutenant Lagow, and another, Lieutenant Hillyer, whom he had known while working from a desk in the St. Louis law firm of McClellan, Moody, and Hillyer. As with others Grant selected, neither would prove to have “any particular taste or special qualifications for the duties of the soldier” and would either resign, as in the case of Lagow, or be dismissed, as was the case with Hillyer.

However, as Grant rose in command and his responsibilities increased, Rawlins became less and less useful. As historian Brooks Simpson notes, “Grant liked Rawlins and valued him for what he could do, but the general also knew his limits: Rawlins could not manage a large military force, provide expert advice, or be trusted to inform other generals of Grant's wishes.” Therefore, Grant would begin to employ Regulars, men with training and experience. Some of these, such as James McPherson, William “Baldy” Smith, and Thomas Wilson, would serve him ably, earn his trust, and be rewarded with combat commands of their own.

Dana would join Grant near Milliken’s Bend, Mississippi in April 1863 and, while Grant never made any specific mention of it in his memoirs nor his personal papers, it would seem obvious that Grant and his staff quickly realized Dana was no mere pay investigator. Grant became aware of Dana’s reports to Stanton, and Dana, who rapidly came to admire and support Grant, functioned as a vital tool in communicating with Stanton and Lincoln. However, Dana was more than that. His observations and views were replied upon by Stanton and became a key part of the decision process in Washington. Further, as he became one of Grant’s biggest supporters, his dispatches and reports influenced Lincoln and Stanton, and fueled Grant’ s continued rise.

In fact, Dana commented on the problems with Grant’s use of his staff and their abilities as they supported operations in the Vicksburg campaign. While Dana admired Rawlins, stating he was “as upright and as genuine a character as I ever came across,” he clearly could see Rawlins’ limitations as well as that of many on the staff. In a letter to Stanton written shortly after the surrender at Vicksburg, Dana provided a compelling picture of the state of affairs in Grant’s staff, stating, “If General Grant had about him a staff of thoroughly competent men, disciplinarians and workers, the efficiency and fighting quality of his army would soon be much increased. As it is, things go too much by hazard and by spasms; or, when the pinch comes, Grant forces through, by his own energy and main strength, what proper organization and proper staff officers would have done already.”

By the time Grant assumed his role as general-in-chief, he had a personal staff of 14 officers, four of them professional soldiers, led by Rawlins, who had risen to the rank of brigadier general and was now Grant’s chief of staff. However, as is given by the term “personal,” this staff became more than just an administrative arm—they were Grant’s trusted inner circle and he used them as his eyes and ears. As the command situations he faced became more complex and his scope of responsibility increased, Grant found he could no longer command on the scene all the time. Therefore, he would use his staff to both carry his written orders to other commanders on the field, and make their own observations of the situation, which they would report to him.

Unlike many other commanders of that time, Grant did not believe in operating via a consensus. Grant would often gather his personal staff and hear their opinions, but, typically, he would conclude those meetings with a strong statement of his personal views, which often contradicted his staff and always were a statement of his final decision. Further, Grant was also reluctant to hold so-called “Councils of War,” wherein a command decision would be reached via a consensus of opinion among his senior commanders. Horace Porter recalled Grant’s reaction to a suggestion that he hold a Council of War.

It was suggested, one evening, that he instruct Sherman to hold a council of war on the subject of the next movement of his army. To this General Grant replied: "No; I will not direct any one to do what I would not do myself under similar circumstances. I never held what might be called formal councils of war, and I do not believe in them. They create a divided responsibility, and at times prevent that unity of action so necessary in the field. Some officers will in all likelihood oppose any plan that may be adopted; and when it is put into execution, such officers may, by their arguments in opposition, have so far convinced themselves that the movement will fail that they cannot enter upon it with enthusiasm, and might possibly be influenced in their actions by the feeling that a victory would be a reflection upon their judgment. I believe it is better for a commander charged with the responsibility of all the operations of his army to consult his generals freely but informally, get their views and opinions, and then make up his mind what action to take, and act accordingly. There is too much truth in the old adage, 'Councils of war do not fight.'"

However, Bragg pursued the defeated Federals and, within a few days, he had successfully bottled them up inside Chattanooga. Unless Rosecrans could affect some meaningful strategy, with his besieged army cut off from any effective means of supply, they were certain to starve, surrender, or be forced to abandon Chattanooga entirely. On September 24, in a flurry of telegrams, Halleck and Stanton, who had already dispatched Sherman to move to Rosecrans’ assistance before Chickamauga, now added the XI and XII Corps of the Army of the Potomac to the mix, ordering them to Chattanooga and placing them under the command of General Joe Hooker.

For his part, Rosecrans simply ceased to be an effective commander and reports direct from none other than Charles Dana added to Lincoln and Stanton’s growing concern about “Old Rosy’s” ability to deal with the crisis. Dana, who had been dispatched to observe and report on Rosecrans, provided first-hand accounts of the disaster at Chickamauga and Rosecrans’ inability to effectively deal with its aftermath. In what was, perhaps, his most scathing assessment of Rosecrans, Dana said that he had never “never seen a public man possessing talent with less administrative power, less clearness and steadiness in difficulty, and greater practical incapacity than General Rosecrans. He has inventive fertility and knowledge, but he has no strength of will and no concentration of purpose.” Continuing, Dana stated that Rosecrans’ “mind scatters; there is no system in the use of his busy days and restless nights, no courage against individuals in his composition, and, with great love of command, he is a feeble commander.” Clearly disturbed by what he was hearing, Lincoln would comment that Rosecrans was not behaving in a way that inspired any confidence in his abilities and that, indeed, he was acting “confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head.”

Dana would also advocate a change of command and recommended Grant as the best man for the job. On September 27, he wrote Stanton, “If it be decided to change the chief commander also, I would take the liberty of suggesting that some Western general of high rank and great prestige, like Grant, for instance, would be preferable as his successor to any one who has hitherto commanded in East alone.” Within days, Stanton was hurrying west by train to implement Dana’s suggestion.

Grant had received orders to proceed with his staff, first, to Cairo, Illinois, and, after arriving there on October 16, he received another telegram directing him to proceed to the Galt House in Louisville, where someone from the War Department would issue him new orders. Grant started to Louisville by train and, while stopped in Indianapolis, he was intercepted by the War Department’s representative, who turned out to be Secretary Stanton himself.

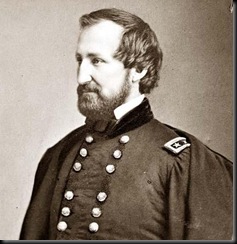

Stanton boarded the train with Grant and, while enroute to Louisville, presented him with two sets of orders and asked that he choose between them. Both sets of orders established a new organizational entity, the Military Division of the Mississippi, which would include all three Federal armies operating in the region: the Army of the Ohio, the Army of the Cumberland, and Grant’s own Army of the Tennessee. Further, both these orders placed Grant in command of the new department. The only difference between the orders was the officer in command of the besieged Army of the Cumberland. Grant was to either leave Rosecrans in command, or replace him with George Thomas. Grant quickly chose the latter.

Grant’s decision to replace Rosecrans with Thomas illustrates another aspect of his personality and how it influenced his command style. As I stated earlier, Grant was often quick to form a strong opinion of a man, and, once he did, little could change his position, often despite evidence to the contrary. Further, once he had formed that opinion, his entire command relationship with that individual would be shaped by that opinion, and it would influence issues of both strategic and tactical planning as well as organization. In Rosecrans case, while Grant had always treated Rosecrans in a professional and even friendly manner, his early experience with him during the Corinth and Iuka campaigns had provided him with a decidedly negative impression.

Stanton, in a telegram sent to Halleck shortly after Grant assumed command of the new division, commented on Grant’s opinion of Rosecrans, stating, “Gen Grant accepted the command at once and has already issued his orders to Thomas. He considers it indispensible that Rosecrans should be relieved because he would not obey orders.” Therefore, based on both Rawlins and Stanton’s statements, it would seem that Grant’s major issue with Rosecrans was insubordination, a trait Grant would not tolerate.

As Grant and Stanton were holding their discussions in Louisville about the situation in Chattanooga, the Secretary of War received a disturbing communiqué from Dana that caused him to believe that Rosecrans and Thomas might be about to abandon Chattanooga. Stanton urged Grant to take action and Grant responded by immediately wiring Thomas, “Hold Chattanooga at all hazards. I will be there as soon as possible. Please inform me how long your present supplies will last, and the prospect for keeping them up.” For his part, the new commander of the Army of the Cumberland quickly responded with a summation of his current stores and bravely concluded, “I will hold the town till we starve.”

Once Grant arrived in Chattanooga, he assumed his characteristically energetic approach to command, personally meeting with all key officers, surveying the field, and immediately ordering actions designed to reopen the line of supply to the starving city. Once the supplies of food and military materiel began to flow, he turned his attentions to matters of strategy. He would soon find that he was in charge of the most complex command problem he had ever faced.

First, there was his scope of responsibility. Instead of being in command of one geographic region among several in the West, he now was responsible for all Federal military operations between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi. As a result, he could not merely focus on the threat to Chattanooga, he had to divide his attention among a large number of issues, both strategic and administrative. Just the fact that he had three armies to command and employ across that region complicated his command challenge.

Additionally, as might be natural with the situation, his plans would now be increasingly affected by political considerations, the best example being support for the Unionist region of Eastern Tennessee. Lincoln had long desired to liberate the loyal and beleaguered population there, and now that accomplishment was being threatened by Confederate pressures against Knoxville. As a result, throughout his tenure in Chattanooga, Grant would find himself dealing with almost constant pressure to provide support to General Burnside’s command in Knoxville, and even suggestions to relieve pressure on Burnside using forces desperately needed to hold Chattanooga.

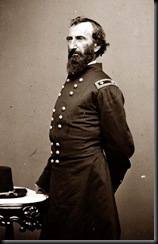

Finally, there was the direct situation that presented itself to Grant in Chattanooga. In crafting a plan to defeat Bragg’s army and break the siege, Grant had to deal with forces from three different Federal armies, with only one on which he felt he could rely. That army was the one he had led, the Army of the Tennessee, and its commander was his most trusted ally and friend, William Sherman. However, the other two were an entirely different matter. From Grant’s point of view, not only did he have a demoralized Army of the Cumberland, led by a passive, slow George Thomas, he also had the potentially unreliable XI and XII Corps from the Army of the Potomac.

Finally, there was the simple fact that Grant was dealing with so many units and commanders who were unknowns to him. Up to now, he had been commanding primarily his army with his commanders. He had some feel for how they might perform, either good or bad. This applied particularly to the commanders. In the past, Grant had learned which commanders could be trusted to follow orders and which ones could not. He had dealt with men like McLernand, knew to watch them carefully, and to always make himself available on-scene, whenever required, to provide the right amount of direct leadership. However, at Chattanooga, with the exception of Sherman and his subordinate units and commanders, he was forced to go purely on instinct and judgments made in a short period of time.

Therefore, as might be expected, when Grant finally decided on his battle plan, he gave the most important assignment to Sherman, while Thomas and Hooker were to play supporting roles. Hooker, with XII Corps in the vanguard, was to make a demonstration on the Confederate left by pressuring Bragg’s forces on Lookout Mountain, while Thomas and the Army of the Cumberland demonstrated against the center on Missionary Ridge. Sherman, meanwhile, was to attack the Southern right on the north end of Missionary Ridge, which was known as Tunnel Hill. From there, he was to roll up Bragg’s flank, at which point Hooker and Thomas could provide support by exploiting Confederate attention on the damage being done by Sherman.

The attack was launched on November 24, when Sherman crossed the Tennessee River, however the major fighting would start in earnest the next day. Sherman’s attack met stiff resistance and, because of an error on the maps, he quickly discovered the terrain on the north end of Missionary Ridge was not as favorable as believed. As a result, by mid-afternoon, the major thrust of Grant’s attack was going nowhere. Nevertheless, at the same time, Hooker, rather than diverting Confederate attention, was rolling up Lookout Mountain and threatening Bragg’s right.

Then, in an effort to relieve the resistance against Sherman, Grant ordered Thomas to have his men go forward and seize the Confederate rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge, hoping that this little demonstration would pose enough threat to Bragg’s center that the Southern commander to pull forces away from his front opposite Sherman. However, just as with everything else in the overall attack plan, Thomas’ demonstration did not proceed as ordered.

As it turned out, Grant did not need to give any more orders. The Army of the Cumberland, who he feared would not leave their trenches, smashed Bragg’s center in six places, sending the Southern army into full retreat. The siege of Chattanooga was broken. Almost nothing of Grant’s plan had gone according to his strategy, and no one had performed according to his expectations. He had been lucky. In his memoirs, he attributed much of his luck to the fact that Bragg had made several serious mistakes, which was somewhat true. However, contrary to his typical nature, he seemed to have learned little else from what, thus far, had been his most complex command challenge. What he should have learned was that, sometimes, even the best general needs a little luck.

Armed with a command style born of considerable experience, and both strengthened and hindered by his own personality, Grant would now take the field as the Army’s General-in-Chief. He would devise a master strategy designed to hammer the Confederacy and bring the war to a swift conclusion. It would require all his considerable strengths and it would tax his own inevitable weaknesses. And, perhaps, that will the subject of a later entry.

No comments:

Post a Comment