In the days and weeks following April 6-7, 1862, Northern papers were filled with news on the struggle at Shiloh. The battle’s eventual casualty totals staggered the nation, both North and South. In only two days of fighting, nearly 24,000 men were dead, wounded, or missing—more than all the battle-related casualties of the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War combined. More controversial, however, was the question of whether or not Union forces were surprised by the Confederate attack, a topic that has been the subject of heated debate ever since.

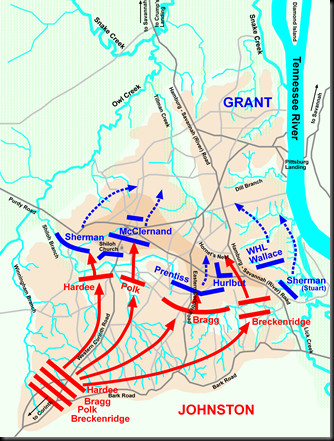

In the meantime, however, there had been important changes in the command picture for both armies. Grant, who had been 10 miles away at Savannah, Tennessee when the fighting began, arrived on the field at around 8:30 in the morning. He immediately began to form strong defensive lines near the river and rally his forces to make a stand. Prentiss’ resistance at the Hornet’s Nest gave him even more time and, when Prentiss surrendered, Union forces were ready to meet any assault. On the Confederate side, General Johnston was mortally wounded during the afternoon and command fell to General Beauregard. Rather than attempting to cut Grant’s force off from the river by concentrating on the Union left flank, Beauregard simply made a series of ineffective frontal assaults on Grant's defensive line that were repulsed at every point.

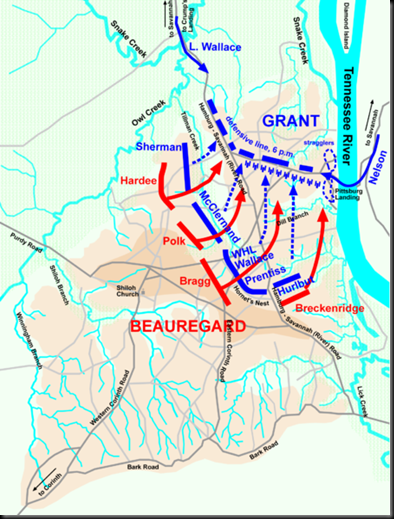

By evening, the two armies faced each other along the final line of battle from the day's fighting. Union forces had been badly beaten up, but remained in position to turn back any renewed assaults. However, as nightfall came, the balance would shift as Buell’s Army of the Ohio began to arrive. Grant now had fresh units to add to his army and his strength increased to nearly 45,000 men. Across the way, Beauregard discounted reports of increasing Federal strength and sent a dispatch to President Davis reporting a “complete victory.” Grant, meanwhile, despite the fearful carnage of Sunday’s fighting, knew he now held the upper hand. During an evening encounter between Grant and Sherman, the Ohio general remarked to Grant, “"Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day, haven't we?" Calm and determined as always, Grant looked up at the man who would become his close friend and replied, "Yes.” Then, taking a puff on his cigar he added, “Yes. Lick 'em tomorrow, though."

The next morning, Beauregard planned to renew his attacks and, hopefully, drive Grant into the river. However, before he could launch his offensive, Grant began a massive counterattack at dawn. Confederate defenders quickly became disorganized under the weight of these attacks. Beauregard would eventually stabilize his lines but, by noon, he was forced to fall back, giving up the ground won at such great cost the day before. In early afternoon, the Confederates attempted a series of counterattacks, but all were turned back. Realizing that he had lost the initiative and that his casualties had been too great to risk continued fighting, Beauregard withdrew beyond Shiloh Meeting House, then began an orderly retreat back to Corinth. Grant’s exhausted men did not pursue and the battle for Shiloh was over.

As I said early on, the issue of whether or not Grant and his forces were surprised at Shiloh was, indeed, a major topic of debate immediately following the battle and has remained so in the years and decades since. Historian Liddell Hart asserts that Grant’s troops were more psychologically than physically surprised, and his position bears further examination. In his book, Sherman: Soldier, American, Realist, Liddell Hart does speak to the fact that Union troops were “physically” ready when Confederate forces attacked in that they were deployed in defensive tactical formations. However, he goes on to say that they were mentally unready for the attack they received. He primarily attributes this to the fact that most were raw and unseasoned units. However, Liddell Hart also states that, while tactical surprise was not achieved, it would appear that strategic surprise was. He believes that, since Grant did not properly deploy his army to take the defensive and, thus set a trap for Johnston, it indicates his offensive mindset caused him to not believe his opponent would take the initiative.

Not surprisingly, in his memoirs, Grant himself makes little mention of the issue of surprise. He does state that he was anticipating a possible enemy foray against his troops at Crump's Landing, some five miles further south down the Tennessee , who were somewhat isolated and exposed. In fact, upon hearing the sound of gunfire on that Sunday morning, he first thought that was exactly what was occurring. After that brief statement, however, the issue of surprise never is mentioned again. The only exception is his reference to the issue of whether his army should have been entrenched. Here, he briefly states that his only engineer was against it and that his army needed discipline and drill more than experience with picks and shovels. This latter statement would seem to bolster Liddell Hart’s analysis that the initial performance of the Army of the Tennessee was more related to the physiological shock received by a green and untrained army than by any issue related to tactical surprise.

What is most interesting about this lack of discussion by Grant is that he personally responded to the question of whether his army was surprised in the weeks following the first allegations. In his book, Grant Moves South, Bruce Catton notes that Grant actually wrote a strongly worded letter to the editor of a Cincinnati paper which had made accusations that Grant’s army was ill-deployed and ill-prepared at Shiloh. Grant told him in no uncertain terms that the army could not have better deployed and more ready than if they had known the time and place of the attack. However, Catton also points out that Grant did admit that he did not anticipate the ferocity or scale of Johnston’s attack. This, therefore, would seem to support Liddell Hart’s strategic surprise argument. Catton notes that Grant’s letter seems to carry a tone with it that seeks more to put the issue of surprise behind him rather than defend his actions prior to the battle. It might be argued, therefore, that Grant was strategically surprised and preferred to place the whole issue to rest lest he become embroiled in accusations and investigations that would serve no further purpose.

Other authors seem split on this issue. In his book, The Rise of U.S. Grant, A.L. Conger mentions the issue of surprise and cites the newspaper coverage of the time. However, he then focuses totally on the tactical surprise angle in defending Grant and his performance. Conger, like Liddell Hart, believes the Union troops at Shiloh were untrained and unprepared for battle and rests the entire surprise issue on that fact.

At the same time, however, Major Matthew Forney Steele took a strong position against Grant. In a lecture given by Steele at Fort Leavenworth in the late nineteenth century and later published in the book, American Campaigns, Steele says unabashedly that Grant did not deploy his army properly. He refers to the Army of the Tennessee as being “exposed” both strategically and tactically. He not only points out the failure to entrench but also the fact that there were virtually no Federal cavalry patrols between Shiloh and Corinth. He further states that Johnston knew this and took advantage of it. In Steele’s words: "Probably there never was an army encamped in an enemy's country with so little regard to the manifest risks which are inseparable from such a situation.” He also notes that, on April 5, Grant had telegraphed Halleck saying that he believed the enemy to still be in Corinth. Steele also is critical of the fact that no defensive actions were undertaken by Grant after relatively large groups of Confederate cavalry were encountered by Federal forces on April 3, 4, and 5. He relates additional reports of Confederate infantry activity from pickets, and believes that the Confederates provided ample warning of their presence. However, Steele points out that, despite this evidence, all Grant’s reports indicate a sublime confidence that the enemy was not present nearby in any strength and that he, not Johnston, would be in control of the offensive initiative.

The actual truth of what happened at Shiloh probably lies in the middle of these varying opinions. It would seem that Grant was, indeed, strategically surprised. He seems to have considered his enemy to be wounded and, therefore, cautious and tentative. Obviously, Grant believed that Johnston was going to consolidate his forces at Corinth and remain on the defensive, allowing Grant time to link with Buell and train his raw troops. Of course, Johnston saw the opportunity presented by Grant’s isolation and also saw the need to strike before Union forces could merge. But, despite some evidence of enemy movement in the area, Grant’s sole concern was the possibility of a smaller attack against his men at Crump’s Landing.

The fact that Grant did not entrench is not so much a concern as the fact that he did not aggressively use his cavalry to reconnoiter and probe for any possible Confederate movements. This seems a clear indicator that he did not anticipate Johnston taking the initiative. Therefore, it seems a logical conclusion to state that Grant was strategically surprised at Shiloh. The question that results from this conclusion is why he let himself be surprised. Was he flush with victory from Forts Henry and Donelson, or, on the other hand, was it mere inexperience?

The latter seems most plausible. The one trait Grant never seems to have exhibited was an excessive ego. To suggest that he was resting on his laurels does not ring true. However, he was still inexperienced. He was new to handling a large army and also was still trying to get a feel for his enemy. Grant would later say that, after Shiloh, he finally realized that the Confederacy would not be beaten easily. Perhaps going into the battle, he believed his enemy’s morale to be low and, thus, saw a vicious, concerted attack as a very low probability. Instead, that is exactly what he got. Grant’s inexperience at this point in his career could also explain, to some extent, his poor use of cavalry to provide intelligence on the enemy. It was a mistake he would not repeat.

The other factor about Grant’s approach, which was criticized in passing by Liddell Hart, was his offensive mindset. However, at this point in the war, given the slow and tentative nature of other Union commanders, this would seem a trait that could be forgiven. It is as though Grant felt that, if he were going to commit an error of judgment, it would be committed while pressing his enemy and trying to retain the initiative. His concept was probably good even if his execution in this case was flawed. The fact that Halleck, once he was in command following Shiloh, believing Grant had been not been cautious enough in his movement to Shiloh, moved slowly forward towards Corinth and, thereby, squandered an opportunity to quickly capitalize on the damage done to the Confederate army, demonstrates why Grant’s approach was a better one in the long run.

The one thing that can be said about Grant is that, while he was far from perfect and could be as prone to errors in military judgment as any general, he learned from his mistakes. His revelation following Shiloh that the war would be long and hard is a clear indicator of that fact.

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

ReplyDeleteYour article is very well done, a good read.