January 30, 1862, was likely a day of anxiety and impatience for Grant. Recently promoted to brigadier general, Grant had been given command of the Federal garrison at Cairo, Illinois, with responsibility for operations from western Kentucky to the mouths of the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers in northwestern Tennessee. For weeks, Grant had been trying to convince his department commander in St. Louis, Major General Henry Halleck, to allow him to undertake the initiative against Confederate forts guarding the Cumberland and Tennessee. To Grant, the value of taking these forts was clear from a strategic point of view, as he would later describe in his memoirs:

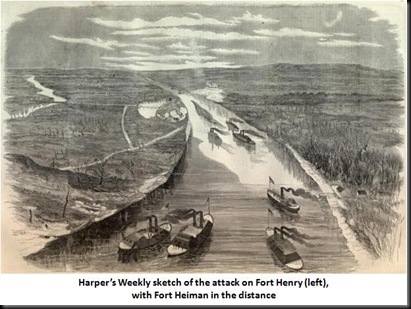

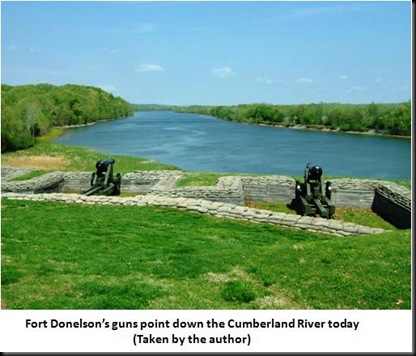

The works on the Tennessee were called Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, and that on the Cumberland was Fort Donelson. At these points the two rivers approached within eleven miles of each other. The lines of rifle pits at each place extended back from the water at least two miles, so that the garrisons were in reality only seven miles apart. These positions were of immense importance to the enemy; and of course correspondingly important for us to possess ourselves of. With Fort Henry in our hands we had a navigable stream open to us up to Muscle Shoals, in Alabama. The Memphis and Charleston Railroad strikes the Tennessee at Eastport, Mississippi, and follows close to the banks of the river up to the shoals. This road, of vast importance to the enemy, would cease to be of use to them for through traffic the moment Fort Henry became ours. Fort Donelson was the gate to Nashville--a place of great military and political importance--and to a rich country extending far east in Kentucky.

In early January, Grant decided to present Halleck with a plan for seizing Forts Heiman, Henry, and Donelson. In a report he sent to Halleck, he closed by stating, “If it meets with the approval of the general commanding the department, I would be pleased to visit headquarters on business connected with this command.” Grant’s plan had been bolstered by a recent expedition down the Tennessee by one of his subordinate commanders, a solid veteran professional soldier, General Charles F. Smith. Smith had been Commandant of Cadets at West Point when Grant went through the academy and he was greatly admired and respected. Smith’s expedition had reconnoitered Fort Heiman and found that it could be easily taken. Heiman dominated the high ground on the opposite side of the river from Fort Henry and, if you could seize it, Fort Henry should fall easily. Grant hoped that now his views on the potential of such a campaign had been confirmed by so able a general as Smith, Halleck would hear him out.

Halleck agreed to see Grant but, as Grant would later recall, “The leave was granted, but not graciously.” When Grant arrived in St. Louis and was ushered into Halleck’s office, the department commander displayed “little cordiality.” As Grant attempted to lay out the proposed plan for the campaign, Halleck abruptly cut him off, indicating that, in his mind, Grant’s ideas were “preposterous.” Grant returned to Cairo “very much crestfallen.”

By late January, Grant calculated that General Smith’s official report must have fallen under Halleck’s eyes, so, on January 28, Grant and Foote sent separate telegrams to Halleck requesting permission to mount their expedition:

CAIRO, January 28, 1862.

Maj. Gen. HENRY W. HALLECK,

Saint Louis, Mo.:

Commanding General Grant and myself are of opinion that Fort Henry, on the Tennessee River, can be carried with four iron-clad gunboats and troops to permanently occupy. Have we your authority to move for that purpose when ready?

A. H. FOOTE, Flag-Officer.

CAIRO, January 28, 1862.

Maj. Gen. H. W. HALLECK.

Saint Louis Mo.:

With permission, I will take Fort Henry, on the Tennessee, and establish and hold a large camp there.

U.S. GRANT, Brigadier General.

Their entreaties were greeted with cold silence as Halleck, again, was paralyzed by his thoughts of all that might go wrong. The next day, Grant would send a more lengthy telegram, urging Halleck to move forward.

HEADQUARTERS DISTRICT OF CAIRO,

Cairo, January 29, 1862.

Maj. Gen. H. W. HALLECK,

Saint Louis, Mo.:

In view of the large force now concentrating in this district and the present feasibility of the plan I would respectfully suggest the propriety of subduing Fort Henry, near the Kentucky and Tennessee line, and holding the position. If this is not done soon there is but little doubt but that the defenses on both the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers will be materially strengthened. From Fort Henry it will be easy to operate either on the Cumberland, only 12 miles distant, Memphis, or Columbus. It will, besides, have a moral effect upon our troops to advance them toward the rebel States. The advantages of this move are as perceptible to the general commanding as to myself, therefore further statements are unnecessary.

U.S. GRANT, Brigadier-General.

However, as fate would have it, Halleck was starting to change his mind, even as Grant sent his latest telegram. Late on January 29, Halleck received a report from General George McClellan indicating that General Beauregard was moving into Kentucky with a Southern army of 15 regiments. The report would prove to be false, but it spurred Halleck to action—it was now critical that the mouths to the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers be seized before Beauregard could move west to reinforce the forts. On January 30, he replied to McClellan that he would order Grant and Foote to “immediately advance, and to reduce and hold Fort Henry, on the Tennessee River.” He then cabled Grant, “Make your preparations to take and hold Fort Henry. I will send you written instructions by mail.”

However, Halleck’s instructions clearly indicated that he was only ordering the capture of Fort Henry and, by implication, Fort Heiman, but not Fort Donelson. His written instructions told Grant to simply take the fort and cut off the roads to Dover and Columbus to prevent either retreat or reinforcement of the Confederate garrisons. Apparently, Halleck intended to have Grant take Fort Henry, then dig in and await events, surrendering the initiative, a concept abhorrent to a commander like Grant.

Grant followed the first group of men in one of the last boats to leave and, the next morning as they moved up the Tennessee, he found that McClernand had wisely ordered the boats to stop about nine miles below Fort Henry and its guns. Grant wanted to get his troops as near to Fort Henry as possible, but without coming within range of the Confederate guns. Grant decided the best way to determine that point was to test the range of Fort Henry’s guns. Therefore, he boarded the gunboat Essex and asked its commander, Captain William Porter, to move upstream, approach the fort, and draw its fire.

Heavy winter rains and even snow upstream was now being felt near the mouth of the river. The current became very swift, and the water was filled with debris in the form of trees, lumber, fences, and huge chunks of driftwood. Worst of all, however, was the rising level of the river. By February 5, as Grant got the last of his men in position north of the fort, the waters of the Tennessee were two feet deep at Fort Henry’s flagpole, and the guns positioned at the lowest level of the fort’s entrenchments were only hours away from being totally submerged. Knowing that Grant’s attack was imminent, Tilghman realized he could not save the fort. Therefore, he decided to send most of his men to Fort Donelson, some 12 miles to the east. He ordered Captain Taylor to remain behind with him, 54 infantrymen, and the gun crews. His hope was to hold for at least an hour once the Federal attack began, and allow the balance of his 2,500 men to reach Donelson.

Grant’s plan now called for a simultaneous assault by both his naval and ground assets on the morning of February 6:

The plan was for the troops and gunboats to start at the same moment. The troops were to invest the garrison and the gunboats to attack the fort at close quarters. General Smith was to land a brigade of his division on the west bank during the night of the 5th and get it in rear of Heiman.

Late that afternoon, Grant sent Halleck the following telegram:

HEADQUARTERS DISTRICT OF CAIRO,

Fort Henry, February 6, 1862.

Fort Henry is ours. The gunboats silenced the batteries before the investment was completed. I think the garrison must have commenced the retreat last night. Our cavalry followed, finding two guns abandoned in the retreat.

I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry.

U.S. GRANT, Brigadier-General.

It is interesting to note that Grant chose to state his plan to immediately move of Fort Donelson, as his orders from Halleck only allowed him to seize Fort Henry. While this might be seen as grandstanding by Grant, that was simply not the case. To Grant, the military situation dictated he move now and seize Donelson, which was a mere 12 miles away. He figured that if he could see Donelson’s importance, surely the Confederates could, as well. With Fort Henry lost to them, Fort Donelson would now be even more critical. Therefore, Grant needed to take Donelson before reinforcements reached the garrison. Plus, he now had the initiative and, demonstrating a command trait that would always remain with him, he now steadfastly refused to surrender that initiative.

Halleck quickly responded to Grant that he was gathering reinforcements and would forward them as quickly as possible, but said nothing approving or disapproving Grant’s move to Fort Donelson. However, Grant inferred from Halleck’s dispatch regarding reinforcements that his superior wanted him to wait and consolidate with these new forces before attacking Fort Donelson. But, to Grant, “15,000 men on the 8th [of February] would be more effective than 50,000 a month later.” He, therefore, ordered Foote to move his gunboats to the Cumberland River and prepared to take Fort Donelson. Ironically, four days later, when he was in front of that very fort, he would finally receive instructions from the ever plodding Halleck to dig in at Fort Henry and await reinforcements. Given the immediate situation, Grant wisely chose to ignore those orders as irrelevant.

As Grant prepared to move on February 7, the weather would, once again, prove to be uncooperative. Torrential rains began to fall and he was forced to postpone his movement across the narrow neck of land between the two Confederate forts. While he delayed, his opponents were embroiled in their own debate as to what they should do about Fort Donelson. For his part, Sidney Johnston saw Grant’s seizure of Fort Henry had created a deep salient into his line in Tennessee and Kentucky. Despite the fact that he had 45,000 men at his command, they were spread thinly, trying to cover the many Federal avenues of attack. As a result, he feared what might happen if he concentrated them to counter Grant, while, at the same time knowing he could ill afford to lose Donelson. Johnston became convinced, however, that he must abandon Fort Donelson and, with it, Nashville, Bowling Green, and Columbus, if he was to save his army.

On that same day, February 7, Johnston went to Bowling Green to meet with General Beauregard, his newly arrived second-in-command, and decide upon a definitive plan of action. He soon found that the vain, touchy Beauregard had differing views. He proposed sending the entire western army to Fort Donelson to smash Grant, re-take Fort Henry, and then sweep into Kentucky to deal with the Union army under General Don Carlos Buell. However, Johnston saw this ambitious plan as fraught with danger. In his mind, if it failed, his army would be destroyed and the entire South west of the Appalachians would be defenseless. In his mind, a general retreat was the only recourse. Still, he needed to do something about Fort Donelson. He could not do what Beauregard proposed but, somehow, he could not bring himself to just abandon the 5,000 men holding the fort without a fight. Therefore, he elected a rather odd middle ground position by sending 12,000 more men to Donelson, hoping to hold it long enough to allow him to get the rest of his army away, then find a way to extract the fort’s garrison before Grant cut them off.

On February 12, the weather lifted and Grant’s small army made the march to Fort Donelson in mild, sunny weather. Unfortunately, in a move many of them would soon regret, his inexperienced volunteer soldiers were enjoying the spring like conditions so much, they elected to discard their heavy blankets and overcoats by the roadside. That night, the Union army arrived at Fort Donelson and began to deploy opposite the fort’s entrenchments. The next morning, February 13, Grant completed his deployments by placing Smith’s division on the left and that of the far less experienced John McClernand on the right.

In the midst of these trials, McClernand decided to make matters worse by ordering his men to assault a Confederate battery, whose dilatory fire apparently annoyed him. The attack was made without authorization from Grant and proved disastrous. The Confederate guns were well fortified and defended, and they dispatched McClernand’s men with ease while inflicting heavy casualties. Many of the Union wounded could not be retrieved and either were burned alive from small wildfires caused by the combination of artillery fire with dry grass and leaves, or slowly froze to death during the night. Needless to say, the morale of those who survived the assault was not high as evening fell.

That night, as his troops huddled in the cold, Grant put his plans for taking the fort into action. His approach would be similar to that employed at Fort Henry. The Navy would play a primary role in the assault, coming up the Cumberland River to bombard the fort, silencing her guns, and doing all the damage possible, while the infantry simply held the line and kept the Confederate garrison contained inside. Then, some of Foote’s small flotilla would run Donelson’s batteries, reaching a point above the fort and the nearby village of Dover, threatening any potential Confederate escape route. Once this was affected, it would be, as Grant would later recall, “but a question of time--and a very short time, too--when the garrison would have been compelled to surrender.”

At a range of 2,000 yards, the St. Louis opened fire, and the rest of the flotilla soon joined in, pounding the Confederate fortifications. Their shells slammed into the earthen walls with ferocity, sending great plumes of dirt skyward, shaking the earth, and creating a great, continuous roar of gunfire and explosions. As the gunboats continued their barrage, Donelson’s gunners did not respond,

The effects were telling. The Carondelet began taking damage almost immediately, as her commander, Commander Henry Walke, would later report:

Soon a 128-pounder struck our anchor, smashed it into flying bolts, and bounded over the vessel, taking away a part of our smoke-stack; then another cut away the iron boat-davits as if they were pipe-stems, whereupon the boat dropped into the water. Another ripped up the iron plating and glanced over; another went through the plating and lodged in the heavy casemate; another struck the pilot-house, knocked the plating to pieces, and sent fragments of iron and splinters into the pilots, one of whom fell mortally wounded, and was taken below; another shot took away the remaining boat-davits and the boat with them; and still they came, harder and faster, taking flag-staffs and smoke-stacks, and tearing off the side armor as lightning tears the bark from a tree.

I was serving the gun with shell. When it exploded it knocked us all down, killing none, but wounding over a dozen men and spreading dismay and confusion among us. For about two minutes I was stunned, and at least five minutes elapsed before I could tell what was the matter. When I found out that I was more scared than hurt, although suffering from the gunpowder which I had inhaled, I looked forward and saw our gun lying on the deck, split in three pieces. Then the cry ran through the boat that we were on fire, and my duty as pump-man called me to the pumps. While I was there, two shots enter our bow-ports and killed four men and wounded several others. They were borne past me, three with their heads off. The sight almost sickened me, and I turned my head away.

This sort of pounding was occurring on all four of the lead ironclads and all were soon in trouble. First, the Louisville dropped out, unable to setter against the current because of damage to her rudder. Aboard the St. Louis, Foote was wounded, the pilot was dead, and the wheel had been blown away. As a result, the flagship of the flotilla was soon out of control, drifting downstream. Meanwhile, both the Pittsburgh and Carondelet were taking on water and had to withdraw, using the smoke from the own guns to mask their retreat. And, despite the resounding barrage from the gunboats, not a single man inside Fort Donelson had been even slightly wounded. As the Union gunboats limped away, the fort’s gunners cheered, having attained a complete and total victory.

With his gunboats damaged and unavailable, Grant now assumed that he would have to lay siege to Donelson until the naval force could return and support his infantry with a long range bombardment. He went to bed on the night of February 14 convinced that he would have to dig in, bring up tents for his troops, and settled in for an extended period. For an aggressive commander, constantly seeking the initiative, this was a gloomy prospect.

Oddly, however, things were even gloomier among Donelson’s commanding triumvirate. Despite their incredible triumph over Foote’s gunboats, they stilled viewed their position as untenable. As the only professional in the group, Buckner could correctly see that it was only a matter of time before Grant would gain the upper hand, trapping the garrison completely and requiring their surrender. Therefore, it would be wise and prudent to affect a breakout, get their men away, and join the main army under Johnston. Floyd and Pillow, meanwhile, agreed simply because they lacked any courage or conviction.

Buckner put together a plan that called for Pillow’s men to come out of their works at first light and attack McClernand’s division on the Federal right. Buckner, meanwhile, would shift all but a regiment of his men from the Confederate right, facing Smith’s division, to the center. Once Pillow had pushed the Union flank back away from the fort, Buckner’s men would attack, holding the door created by Pillow’s attack open, allowing Pillow’s men to march along the river to safety. Buckner would then fight a rear-guard action until he too could escape. If Grant pursued, the entire Confederate force would find ground to their liking, and then turn and fight in the open.

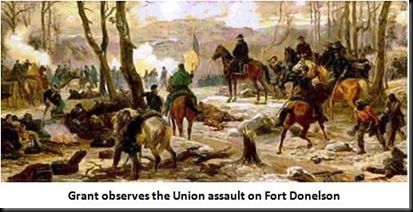

As February 15 dawned, the Confederates inside Fort Donelson were ready. They had prepared all during the cold, wintry night and lay poised to breakout. As they crouched in their trenches, Ulysses Grant rode his horse down the frozen roads to the north to meet with Foote for discussions on the status of the fleet and the fate of their joint expedition. Grant had no reason to expect an attack and he directed his staff to let all division commanders he would be absent and to do nothing that might spark an engagement. But, while Grant was meeting with Foote, the Confederates launched their own attack.

Luckily for Grant, Gideon Pillow was not up to carrying out the limited assignment he had undertaken. As his men surged forward, Pillow suddenly decided to fall back to the entrenchments. Buckner, meanwhile, had moved his men and secured the road to Nashville for their escape, as planned. Furious, he strode up to Pillow and told him to get his men moving, as the door to escape was now open. Pillow refused and ordered Buckner to bring his men back to the fort. Buckner angrily refused to do so. At this moment, General Floyd appeared, listened to Buckner’s arguments, and agreed that it was time to escape. However, Pillow quickly took his fellow politician aside, whispered to him, and Floyd changed his mind, agreeing that they must return to the trenches. In disgust, Buckner returned to his men and began withdrawing them from the Nashville road.

I turned to Colonel J. D. Webster, of my staff, who was with me, and said: “Some of our men are pretty badly demoralized, but the enemy must be more so, for he has attempted to force his way out, but has fallen back: the one who attacks first now will be victorious and the enemy will have to be in a hurry if he gets ahead of me." I determined to make the assault at once on our left. It was clear to my mind that the enemy had started to march out with his entire force, except a few pickets, and if our attack could be made on the left before the enemy could redistribute his forces along the line, we would find but little opposition except from the intervening abatis. I directed Colonel Webster to ride with me and call out to the men as we passed: "Fill your cartridge-boxes, quick, and get into line; the enemy is trying to escape and he must not be permitted to do so." This acted like a charm. The men only wanted some one to give them a command.

The three generals listened, but, in the end, they all agreed to surrender. However, both Floyd and Pillow had one reservation to the surrender plan. It seems that, while they were willing to surrender the fort and all of their men, they were unwilling to surrender themselves. Pillow, seeing himself as a very important figure in the Confederacy, stated that his capture by the Federals would be a disaster. Floyd, meanwhile, feared that he might be tried on old charges that, while serving as Secretary of War, he had made fraudulent deals, misappropriated funds, and secretly transferred arms to the emerging Confederate government. There then followed a truly bizarre conversation in which Buckner, ever the soldier, said that he would surrender the fort and share his men’s fate. Floyd then announced that he was passing overall command to Pillow, who summarily stated that he, in turn, was passing it on to Buckner. So, the professional soldier would be left to his fate while the two politicians headed for the hills and saved their own skins.

Young Forrest listened to all this in complete amazement, then barked that he had no intention of surrendering his men. He stormed out, collected his officers and told them they were going to escape or die trying. They all stood with him, then assembled the regiment and made a daring nighttime escape attempt via the narrow road the scouts had discovered earlier. The road was partially submerged under the freezing waters of the Cumberland in places, but Forrest’s men would make a successful escape.

The next morning, Buckner called for a courier, and gave him a message to be carried under a flag of truce to his old comrade, General Grant:

HEADQUARTERS, Fort Donelson, February 16, 1862.

SIR: In consideration of all the circumstances governing the present situation of affairs at this station I propose to the commanding officers of the Federal forces the appointment of commissioners to agree upon terms of capitulation of the forces and post under my command, and in that view suggest an armistice until 12 o'clock to-day.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

S. B. BUCKNER, Brigadier-General, C. S. Army.

Grant received the message and considered the idea of holding a conference with Buckner, given their former friendship and the kindness Buckner had once done him. But, he could not bring himself to do so and quickly penned a reply that would become famous for its direct and unambiguous nature:

HEADQUARTERS ARMY IN THE FIELD,

Camp near Fort Donelson, February 16, 1862.

SIR: Yours of this date, proposing armistice and appointment of commissioners to settle terms of capitulation, is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

U.S. GRANT, Brigadier-General, Commanding.

Buckner would reply that, while he saw Grant’s answer as “ungenerous and unchivalrous,” he had no real alternative. A few minutes later, to the resounding cheers of Grant’s soldiers, the Confederate colors flying over Fort Donelson were lowered. A short while thereafter, Grant would meet Buckner at the Dover Inn.

Grant then asked about the whereabouts of General Pillow. Buckner replied that he had fled, telling Grant that Pillow “thought you’d rather get hold of him than other man in the Southern Confederacy.” Grant smiled at that, saying, “Oh, if I had him, I’d let him go again. He will do us more good commanding you fellows.”

Grant then telegraphed Halleck to inform him of Fort Donelson’s fall. The word quickly spread across the North, and touched off celebrations everywhere. In St. Louis, the Union Merchant’s Exchange closed down, as members sang patriotic songs, then marched to Halleck’s headquarters to cheer with the rest of crowds converging there in celebration. Grant became an overnight hero, much to Halleck’s chagrin. His call to Buckner for surrender electrified the populace and he became known everywhere as “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

In a the larger picture, however, the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers were now in Union hands, and the two rivers pointed south like daggers poised at the heart of the Confederacy. Sidney Johnston would be forced to withdraw from Tennessee and Kentucky after all, and now with 12,000 men less than he had before. Within days, Nashville fell to Union forces, never to return to Confederate control again. As for Ulysses Grant, he had started a bow wave of victorious momentum in the West that would not be stopped. And, in doing so, he displayed for the first time, a few of the skills that he would demonstrate as a commander over and over: tenacity despite adversity, seizure of the initiative, and a clear, common sense vision of the tasks that must be done.

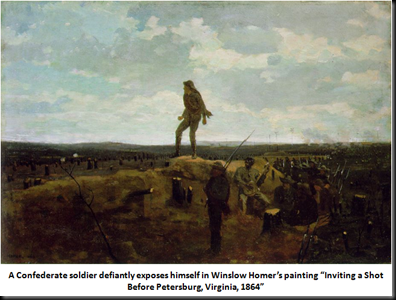

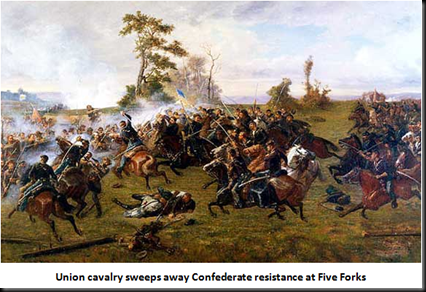

At Grant’s headquarters, there was much celebration the night of April 1. The only pall on the moment was the news that, in the midst of the fighting at Five Forks, Sheridan had relieved Warren of command. But, Grant knew that probably had to be done and, now, there were bigger issues. Grant knew the pressure the fall of Five Forks had put on Lee and he saw what was, perhaps, the greatest opportunity of the war in front of him. After a brief moment of reflection, he penned an order for a massive assault along the entire Petersburg line for the next morning, 4:00 a.m. on April 2. The door had been pushed ajar; all he need do now was open it.

At Grant’s headquarters, there was much celebration the night of April 1. The only pall on the moment was the news that, in the midst of the fighting at Five Forks, Sheridan had relieved Warren of command. But, Grant knew that probably had to be done and, now, there were bigger issues. Grant knew the pressure the fall of Five Forks had put on Lee and he saw what was, perhaps, the greatest opportunity of the war in front of him. After a brief moment of reflection, he penned an order for a massive assault along the entire Petersburg line for the next morning, 4:00 a.m. on April 2. The door had been pushed ajar; all he need do now was open it.