In late March 1865, central Virginia was awash in steady rain. Streams and rivers were swollen, and even roadways seemed to disappear, either turning into small streams themselves or simply becoming deep, muddy quagmires. The rain made life in the trenches around Petersburg even more miserable for the men of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. This once proud army was a mere shadow of the one that had seen such brilliant victories over the Union’s Army of the Potomac in the three years preceding. Now, with the war’s tide having steadily turned, casualties, desertions, and disease had withered the ranks. As the men huddled in their trenches, where they had been since the summer before, their rations consisted primarily of parched corn and their patchwork uniforms literally fell from their backs. Still however, among the core of the army’s men, among those who resolutely remained in the line, there still was a belief that, somehow, Lee would find a way. As a result, they had stubbornly held on, throwing back every attempt the Union forces made to break through.

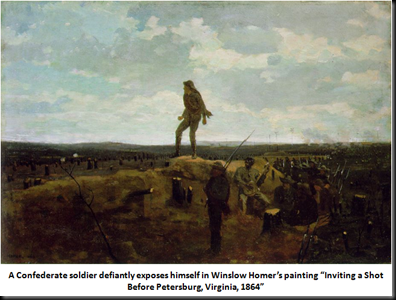

Throughout the summer and fall the year before, there had been attempts to break the Confederate fortifications using bombardment, direct frontal assaults, and even mining underneath the trenches to set off an enormous explosion. All had failed and, with winter, both sides settled in to watch one another across what was, arguably, warfare’s first “no man’s land.” However, as spring arrived, the indomitable Ulysses S. Grant began to once again actively seek that opening, and believed he saw one on Robert E. Lee’s right flank.

Grant envisioned a field of operations bounded by the Southside Railroad on the north, the Weldon Railroad on the east, Vaughn Road to Dinwiddie Court House on the south, and on the west by the road leading north from Dinwiddie Court House to the Southside Railroad through a crossroads known as Five Forks. Grant’s original plan was to march two infantry corps, the II and V, to a position on the Confederate far right, then have them move towards the Southside Railroad, forcing Lee’s men to come out of the trenches and fight.

The rains continued unabated on March 30, and both the Federal infantry and cavalry made slow progress. As they continued a slow advance, Grant had a change of heart, either because he saw an opportunity or a long desired plan now seemed possible. With Lee’s movement of cavalry and infantry to the Confederate right, Grant told Sheridan to abandon the plan to raid the railroad, stick close to the infantry, and see if there was an opportunity to turn Lee’s right and get behind him. Sheridan responded by sending Generals Merritt and Devin’s cavalry to Five Forks to see if they could occupy and hold it. However, a few miles from the crossing, they ran into Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry and a nasty skirmish ensued. Hearing that Confederates cavalry was already at Five Forks and with the continuing deluge, Grant sent word to Sheridan to suspend the attack planned for the next day, March 31.

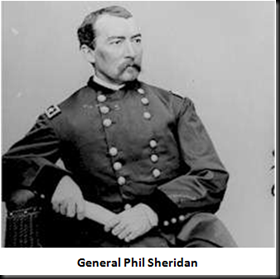

When Sheridan received Grant’s note, he was utterly distraught. He mounted his horse and rode through the driving rain to Grant’s headquarters, his mount “plunging at every step almost to the knees in mud.” Horace Porter, a member of Grant’s staff, later recalled the meeting with Sheridan:

As soon as Sheridan dismounted he was asked with much eagerness about the situation on the extreme left. He took a decidedly cheerful view of matters, and entered upon an animated discussion of the coming movements. He said: "I can drive in the whole cavalry force of the enemy with ease, and if an infantry force is added to my command, I can strike out for Lee's right, and either crush it or force him to so weaken his intrenched lines that our troops in front of them can break through and march into Petersburg." He warmed up with the subject as he proceeded, threw the whole energy of his nature into the discussion, and his cheery voice, beaming countenance, and impassioned language showed the earnestness of his convictions.

As he paced up and down, “chafed like a hound in the leash,” Sheridan told Porter and the staff that, “I 'm ready to strike out to-morrow and go to smashing things!" Porter wrote that Sheridan was hesitant to give the general-in-chief advice when none had been requested. So, one of the staff went in to tell Grant that Sheridan was outside with some interesting news. The commanding general asked that they let Sheridan into his tent so that he could discuss this news with him. After listening to Sheridan, Grant was impressed with the Irishman’s arguements, as well as his enthusiasm:

Sheridan felt a little modest about giving his advice where it had not been asked; so one of my staff came in and told me that Sheridan had what they considered important news, and suggested that I send for him. I did so, and was glad to see the spirit of confidence with which he was imbued. Knowing as I did from experience, of what great value that feeling of confidence by a commander was, I determined to make a movement at once…Orders were given accordingly.

However, things did not go well and, initially, certainly not as Sheridan had hoped. The same evening Sheridan met with Grant, Merritt’s cavalry discovered that Pickett’s division of infantry was entrenched at Five Forks.

The problem was not with the men of the V Corps, but rested with Warren himself. A fine officer who had accumulated an enviable war record, Warren had become increasingly unstable in the last few months. He now tended to be slow and overly cautious. This concerned both Sheridan and Grant, and, as Grant later wrote,

I was very much afraid that at the last moment he would fail Sheridan. He was a man of fine intelligence, great earnestness, quick perception, and could make his dispositions as quickly as any officer, under difficulties where he was forced to act. But I had before discovered a defect which was beyond his control, that was very prejudicial to his usefulness in emergencies like the one just before us. He could see every danger at a glance before he had encountered it. He would not only make preparations to meet the danger which might occur, but he would inform his commanding officer what others should do while he was executing his move.

As a precaution, Grant sent one of his staff to Sheridan, telling him that, “as much as I liked General Warren, now was not a time when we could let our personal feelings for any one stand in the way of success; and if his removal was necessary to success, not to hesitate.”

On March 31, as Warren’s V Corps slowly moved to join with Sheridan, Pickett surprised Sheridan by moving his force of cavalry and infantry forward from Five Forks. His plan was to push Sheridan back by attacking the Union left flank near Dinwiddie with infantry, as his cavalry wheeled in from the west. The plan worked to near perfection and, rather than advancing, Sheridan found himself falling back to just north of Dinwiddie, where he established a defensive line that was able to finally stop Pickett. As this was occurring to Sheridan and his cavalry, V Corps was attacked by Confederate infantry under General Bushrod Johnson as they moved up the White Oak Road. The fighting was brief, but savage, with V Corps being pushed back at first, then finally counterattacking to regain the lost ground. But, this fighting had further delayed their progress to get into position.

At this moment, as members of Sheridan’s staff wondered aloud if the planned attack should be shelved, Sheridan continued to show his determination. He told Porter, whom Grant had dispatched to assess the situation, that Pickett was now the one in trouble and that the situation presented even more of an opportunity. He told Porter, “This force is in more danger than I am. If I am cut off from the Army of the Potomac, it is cut off from Lee's army, and not a man in it ought ever be allowed to get back to Lee. We at last have drawn the enemy's infantry out of its fortifications, and this is our chance to attack it.”

For his part, Warren, despite receiving confusing and contradictory orders from Sheridan, Meade, and Grant, conceived a plan for employing his corps that would trap Pickett. He proposed that he move V Corps west, striking Pickett from one side, while Sheridan and the cavalry hit the Confederates from the other side. Grant approved the idea and told Warren to get his corps in motion and not to stop for anything. Then, he sent word to Sheridan of the plan, telling him that Warren would be in position by midnight. Unfortunately, however, Warren’s march became a confused mess and he did not even start to move until 6:00 a.m. the morning of April 1.

Across the lines, George Pickett had his own worries. Just as Sheridan had observed, Pickett knew that his force was very exposed in this advanced position. His worries only increased when he heard about the fighting on White Oak Road and learned that Federal prisoners taken in the battle were from V Corps. Realizing that he might not only be facing Sheridan’s cavalry but also infantry, Pickett knew he had to fall back to a more defensible position. He immediately retreated back to the lines commanding the crossroads at Five Forks and had his men work to build up their field fortifications. Once his men were back in position at Five Forks, Pickett informed Lee of his decision, and the commanding general was not pleased. Lee responded tersely, “Regret exceedingly your forced withdrawal, and your inability to hold the advantage you had gained. Hold Five Forks at all hazards.”

As a result of Pickett’s retreat, when Warren finally got his first divisions in place near Dinwiddie at 7:00 a.m., they discovered that Pickett was gone. Sheridan was furious and felt that Warren was “living down” to his already low expectations. Still, upon learning that Pickett was back in his fortifications at Five Forks, Sheridan devised an innovative plan of attack. He would dismount his cavalry and attack in a feint designed to pin down Pickett’s right and center, while Warren’s infantry attacked the Confederate left from the southeast at a 45-degree angle, striking the point where Pickett had bent his line at 90-degrees to protect the left flank.

Warren met with Sheridan early that afternoon to discuss the plan and seemed to grasp it immediately. However, Sheridan still worried that Warren’s heart was not in the job at hand and, soon, reports were coming in indicating that, once again, the V Corps was not moving swiftly into place. Sheridan fretted that Warren would not be ready to attack before sunset and that his tardiness would allow another day to slip away. But, by 4:00 p.m., Warren’s men were in-place and ready for the attack.

On the Confederate side, the afternoon of April 1 was a quiet one. As yet, Pickett had received no more information on the presence of V Corps and was confident for now that his men could turn back any attack by Sheridan’s cavalry. As a result, he and Fitzhugh Lee accepted an invitation from Thomas Rosser to attend a shad-bake at his camp on the north bank of Hatcher’s Run. Shad were a local fish and shad-bakes were a regional rite of spring for Tidewater Virginians. As there seemed no immediate threat, Pickett decided that he could use a good meal and a few hours of relaxation, so, around 2:00 p.m., he and his cavalry companion rode off without telling anyone where they might be found or when they would return. In fact, Pickett’s other cavalry division commander, Rooney Lee, did not even know Pickett had left the area and Pickett did not assign anyone to be in command during his absence.

A few hours after Pickett left, Confederate observers at Five Forks could clearly see the blue-clad infantry of V Corps moving into position on their left. One of Pickett’s division commanders, Thomas Mumford, sent a courier in search of Fitzhugh Lee and Pickett to inform them that an attack by Federal infantry was imminent But, the courier could not find either officer. Other riders were sent out but they were also unsuccessful in their search for the missing commanders. As a result, when the attack came, no one was in overall command.

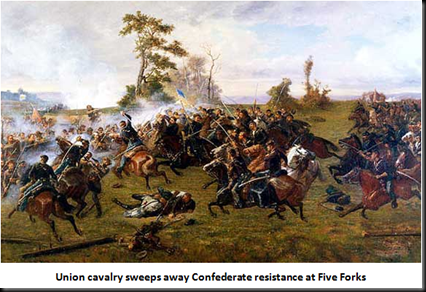

As it happened, the Federal attack did not go as planned. The angle in Pickett’s line was actually concealed in dense woods and was much further west than Sheridan believed. As a result, the division intended to strike the front of Pickett’s line under General Ayres actually ended up attacking the angle itself. Ayres wheeled his men toward the angle while the divisions of Crawford and Griffin, whom Ayres needed for support if he were to carry the Confederate barricades, marched off past the angle and both missed Pickett’s line completely. However, quick thinking by Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, the professor-soldier and hero of Little Round Top at Gettysburg, helped turn things right. Commanding a brigade in Griffin’s division, he noted with grave concern the growing gap between his brigade and Ayres division, which he could see was heavily engaged attacking the angle. Exercising superb command judgment, he turned his brigade and attacked on Ayres right. Upon seeing Chamberlain’s bold move, Griffin realized what was happening and followed with the rest of his division.

Sheridan now rushed into the midst of the broken lines, and cried out: "Where is my battle-flag?" As the sergeant who carried it rode up, Sheridan seized the crimson-and-white standard, waved it above his head, cheered on the men, and made heroic efforts to close up the ranks. Bullets were now humming like a swarm of bees about our heads, and shells were crashing through the ranks. A musket-ball pierced the battle-flag; another killed the sergeant who had carried it; another wounded an aide, Captain McGonnigle, in the side; others struck two or three of the staff-officers' horses. All this time Sheridan was dashing from one point of the line to another, waving his flag, shaking his fist, encouraging, entreating, threatening, praying, swearing, the true personification of chivalry, the very incarnation of battle.

As the men of the V Corps climbed over the barricades and into the Confederate line, Sheridan spurred Rienzi forward, leaping the breastworks, landing among a group of quickly surrendering Confederate soldiers. Some of the prisoners called out to Sheridan, saying, "Wha' do you want us all to go to?" Sheridan's rage turned quickly to humor, and, as they filed past, the general shouted, "Go right over there," pointing to the rear. "Get right along, now. Oh, drop your guns; you'll never need them any more. You'll all be safe over there. Are there any more of you? We want every one of you fellows."

As for General Pickett, once the Federal attack was underway, he was still unaware of what was happening to his command. He and Fitzhugh Lee had lingered at Rosser’s headquarters after lunch, savoring what was probably the best meal they had in weeks, and sharing some alcoholic beverages with their comrades. Soon, a courier dashed into the camp to tell the Confederate generals that Union forces were moving up on the White Oak Road. Pickett listened intently for the sounds of gunfire, but heard nothing, as the dense pine forest between them and Five Forks muffled the sound of battle.

As a precaution, Pickett asked Rosser to send two men as couriers to determine what might be happening at Five Forks, with one following the other by several hundred yards to prevent both from falling captive should they be intercepted. The riders dashed out of camp and, within minutes, Pickett and his cavalry generals heard the sounds of gunfire. They looked down the road and saw Federal cavalry dash out from the woods to seize the first courier. The second courier turned about and galloped back to Pickett, shouting, “Woods full of ‘em, sir! They’ve got behind the men at Five Forks, too!”

Pickett immediately leaped on his horse and headed for Five Forks. However, he found the way blocked by Union infantry from Crawford’s division. He appealed to his cavalry escort to punch a hole for him to ride through, which they did. Riding “Indian-style,” with his head bent down behind his horse’s neck, Pickett dashed through a hail of Federal bullets to finally reach his command. However, it was too late. Attacked from three sides by Warren’s infantry and Sheridan’s cavalry, Pickett’s line had disintegrated. The astonished Confederate general tried to fight a final stand using a single Virginia brigade but Crawford’s men soon overran the outmatched Confederates.

It is nice to have one source to gain valuable history lessons from, as well as the personal info. added, making it all hit home quite nicely! Throwing in the more than appropriate pictures is frosting on the cake. :-)

ReplyDeleteGood job! Good job!