In every conflict throughout history, there are military organizations that are anointed as being “legendary” for their fighting ability, their tenacity, and their toughness. From King Leonidas’ 300 Spartans to the 101st Airborne Division’s “Battered Bastards of Bastogne,” certain units stand out both in popular memory as well as within the community of military historians. And, to be certain, the American Civil War had its own share of such units. Ironically, one of these, a brigade of the Union Army, would initially achieve its status as a legend by standing toe-to-toe with another legendary unit, the Stonewall Brigade of General Thomas “Stonewall”  Jackson’s famous “foot cavalry.” The fighting between these two groups would take place in the dim light of a sweltering August evening in 1862 at an obscure place known as Brawner’s Farm.

Jackson’s famous “foot cavalry.” The fighting between these two groups would take place in the dim light of a sweltering August evening in 1862 at an obscure place known as Brawner’s Farm.

In the late summer of 1862, General George McClellan, who had managed to lose to inferior numbers repeatedly in the Seven Days' Battles near Richmond, sat with the Army of Potomac at Harrison's Landing on the James River, having been relieved from his position as General-in-Chief of the U.S. Army. While McClellan would remain in command of the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln replaced him as head of the army with General Henry Halleck. Halleck, in turn, decided to create a new Union army, the Army of Virginia, under the command of General John Pope, who promised Lincoln great victories.

By late July 1862, Pope had placed his army on the north side of the Rappahannock River facing General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. With much bombast and bragging, Pope had moved out and engaged Jackson at Cedar Mountain on August 9. Pope lost the engagement decisively and, as a result, he now became timid and, in fact, seemed to become completely confused. Pope placed his army in defensive positions along the Rappahannock, hoping to draw Lee away from McClellan so that McClellan could extract his army from the James Peninsula and unite with Pope. But, McClellan was slow, as always and, frankly, was secretly hoping something would happen to embarrass Pope. General Lee obliged him.

By late July 1862, Pope had placed his army on the north side of the Rappahannock River facing General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. With much bombast and bragging, Pope had moved out and engaged Jackson at Cedar Mountain on August 9. Pope lost the engagement decisively and, as a result, he now became timid and, in fact, seemed to become completely confused. Pope placed his army in defensive positions along the Rappahannock, hoping to draw Lee away from McClellan so that McClellan could extract his army from the James Peninsula and unite with Pope. But, McClellan was slow, as always and, frankly, was secretly hoping something would happen to embarrass Pope. General Lee obliged him.

Lee decided to strike north and move the war away from Richmond, possibly even into the northern states. So, he ordered Stonewall Jackson and General James Longstreet to march around Pope's right flank and then turn through Thoroughfare Gap to get between Pope's army and Washington. Jackson moved out first in the early morning darkness of August 25 and headed towards White Plains. By nightfall, his army was rapidly approaching their initial objective while General Longstreet prepared to move the next afternoon.

Pope received information that Jackson was on the move late on August 25, but seemed completely baffled about exactly what to do. He finally ordered his army to begin a search for Jackson and had his divisions marching up and down the northern Virginia countryside in a futile attempt to locate the wily Confederate general. Then, on the night of August 27, Jackson's forces struck the Union supply depot at Manassas Junction, destroying massive quantities of Federal supplies, including Pope’s new dress uniforms. Pope now realized that Jackson was in his rear and, worse, was between his army and Washington. To his credit, however, he realized that since Longstreet was still moving towards Thoroughfare Gap and, thus, was separated from Jackson, an opportunity existed to destroy Jackson’s corps before Longstreet arrived. He quickly ordered the army to concentrate east towards Manassas Junction. Unfortunately, Jackson was too quick for Pope. On August 28, Jackson proceeded to double back and place himself northeast of Manassas Junction, just north of the Warrenton Pike near the village of Groveton. Pope again lost all track of Jackson and ordered his still scattered forces to locate the Confederates. As he would soon find out, Jackson had placed his men in a strong hidden defensive position along an abandoned railroad cut amid heavy trees, anxious to have a go at John Pope.

Pope received information that Jackson was on the move late on August 25, but seemed completely baffled about exactly what to do. He finally ordered his army to begin a search for Jackson and had his divisions marching up and down the northern Virginia countryside in a futile attempt to locate the wily Confederate general. Then, on the night of August 27, Jackson's forces struck the Union supply depot at Manassas Junction, destroying massive quantities of Federal supplies, including Pope’s new dress uniforms. Pope now realized that Jackson was in his rear and, worse, was between his army and Washington. To his credit, however, he realized that since Longstreet was still moving towards Thoroughfare Gap and, thus, was separated from Jackson, an opportunity existed to destroy Jackson’s corps before Longstreet arrived. He quickly ordered the army to concentrate east towards Manassas Junction. Unfortunately, Jackson was too quick for Pope. On August 28, Jackson proceeded to double back and place himself northeast of Manassas Junction, just north of the Warrenton Pike near the village of Groveton. Pope again lost all track of Jackson and ordered his still scattered forces to locate the Confederates. As he would soon find out, Jackson had placed his men in a strong hidden defensive position along an abandoned railroad cut amid heavy trees, anxious to have a go at John Pope.

All Jackson needed was an opening, a chance, designed to let Pope know where he was, bring his opponent to him on ground of his choosing, and, at the same time, issue a sudden, crushing blow to some unsuspecting piece of Pope’s still scattered army. On the late afternoon of August 28, that opportunity seemed to present itself. From his hidden position, Jackson watched as several Union units marched past him, heading east on the Warrenton Pike toward Centerville. Finally, he observed a division of blue-clad infantry making its way along the road, its brigades somewhat separated from one another, leaving each one vulnerable. He could tell these men had been marching all day in the stifling, humid Virginia heat, their formations becoming a bit ragged as the tired soldiers plodded along the dusty road. He let the first brigade pass, and waited for the second, which followed by about a quarter-mile. Had he known that only one of the four regiments in this brigade had seen any fighting thus far, he would have been certain that this was the time and place to strike. Further, he could see that this brigade had about 2,000 men, while he had several thousand immediately available, and another 20,000 nearby. The situation was very nearly perfect. He turned to his staff and said, “Bring out your men, gentlemen.” However, Jackson would soon learn that he had picked the wrong Union brigade with which to trifle.

All Jackson needed was an opening, a chance, designed to let Pope know where he was, bring his opponent to him on ground of his choosing, and, at the same time, issue a sudden, crushing blow to some unsuspecting piece of Pope’s still scattered army. On the late afternoon of August 28, that opportunity seemed to present itself. From his hidden position, Jackson watched as several Union units marched past him, heading east on the Warrenton Pike toward Centerville. Finally, he observed a division of blue-clad infantry making its way along the road, its brigades somewhat separated from one another, leaving each one vulnerable. He could tell these men had been marching all day in the stifling, humid Virginia heat, their formations becoming a bit ragged as the tired soldiers plodded along the dusty road. He let the first brigade pass, and waited for the second, which followed by about a quarter-mile. Had he known that only one of the four regiments in this brigade had seen any fighting thus far, he would have been certain that this was the time and place to strike. Further, he could see that this brigade had about 2,000 men, while he had several thousand immediately available, and another 20,000 nearby. The situation was very nearly perfect. He turned to his staff and said, “Bring out your men, gentlemen.” However, Jackson would soon learn that he had picked the wrong Union brigade with which to trifle.

The Union brigade that marched up the Warrenton Pike that evening was, indeed, more than a little green. Its four regiments included the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments, along with the 19th Indiana, but only the 2nd Wisconsin had seen any fighting  thus far. They were one of the few brigades in the eastern Union armies from what was then called the West, and they were a group of tough, hardened men, lumberman and pioneer farmers, led by one the best officers in the Union Army, Brigadier General John Gibbon.

thus far. They were one of the few brigades in the eastern Union armies from what was then called the West, and they were a group of tough, hardened men, lumberman and pioneer farmers, led by one the best officers in the Union Army, Brigadier General John Gibbon.

Gibbon was a professional soldier, a West Point graduate, and, oddly, a Philadelphia-born North Carolinian. His three brothers chose to fight for the Confederacy, but Gibbon found he could not turn his back on the oath he had taken at West Point. Gibbon was a ramrod-straight man, 35 years old, and a former artillery officer who had fought in Mexico and against the Seminoles in Florida. His men, meanwhile, had spent most of the war thus far training in camps along the Potomac and guarding railroads. Gibbon became their brigade commander in June 1862, and by this point, he and his men had come to respect, but not love, each other. Gibbon demanded the same level of discipline and professionalism from these volunteer westerners as he  demanded of his Regular artillerymen. One soldier would later remark, “Until we learned to know him, which we did not till he led us in battle, we seemed very far apart.” Gibbon later explained how difficult it was to train men who not only had recently been civilians, but were independent frontier men, filled with a rambunctious, undisciplined spirit: “The habit of obedience and subjection to the will of another, so difficult to instill into the minds of free and independent men, became marked characteristics of the command. A great deal of the prejudice against me as a Regular officer was removed when the men came to compare their own soldierly appearance and way of doing duty with other commands….”

demanded of his Regular artillerymen. One soldier would later remark, “Until we learned to know him, which we did not till he led us in battle, we seemed very far apart.” Gibbon later explained how difficult it was to train men who not only had recently been civilians, but were independent frontier men, filled with a rambunctious, undisciplined spirit: “The habit of obedience and subjection to the will of another, so difficult to instill into the minds of free and independent men, became marked characteristics of the command. A great deal of the prejudice against me as a Regular officer was removed when the men came to compare their own soldierly appearance and way of doing duty with other commands….”

Gibbon’s command had been placed in Pope’s new army, as the 4th Brigade, 1st Division, of Major General Irvin McDowell’s III Corps. They had also already achieved a nickname as the “Black Hat” Brigade because, rather than the standard Union kepi, they wore black Hardee hats, also known as the Model 1858 Dress Hat, which was the regulation dress hat for enlisted men in the Union Army. These tall, almost “top hats,” were adorned with a plume, giving the brigade a very distinctive appearance.

Gibbon’s command had been placed in Pope’s new army, as the 4th Brigade, 1st Division, of Major General Irvin McDowell’s III Corps. They had also already achieved a nickname as the “Black Hat” Brigade because, rather than the standard Union kepi, they wore black Hardee hats, also known as the Model 1858 Dress Hat, which was the regulation dress hat for enlisted men in the Union Army. These tall, almost “top hats,” were adorned with a plume, giving the brigade a very distinctive appearance.

As Jackson watched the Black Hats trudge down the pike, the clock was fast approaching 6:00 p.m. and the sun was already beginning to disappear behind the mountains to the west. He probably could see John Gibbon riding ahead of his men, reading a map and often gazing at the trees and hilly terrain to the north of the pike. Meanwhile, Gibbon’s westerners were almost certainly thinking about reaching Centerville, where they would join the rest of the army and bed down after a long day of marching. Therefore, the carnage that was about to ensue was nowhere in their thoughts.

Suddenly, as Gibbon peered to the north, towards the dense forest around the old abandoned railroad grade, he noticed horsemen near the Brawner farmhouse and wondered if they might be enemy cavalry. He casually rode his horse off the pike in an attempt to gain a better view of the gray horsemen. Within seconds, he realized that these men were not cavalry, but were Confederate artillery, which were even now quickly unlimbering their guns for action. Before he could turn and warn his command, at least two Southern batteries opened fire on his brigade and those trailing behind it, all of which were still marching in column along the pike.

As shells screamed overhead and exploded around them, some of the Union column quickly scattered, as ambulances and wagons careened panic-stricken off the road into the fields and forests south of the pike. The New York regiments in General Patrick’s brigade, which was about 1,000 yards behind Gibbon, immediately broke up and headed for the trees—they would never participate in the fight to come despite Gibbon’s pleas for help and it would be hours before they would finally re-form.

Gibbon, meanwhile, kept his head like the professional that he was. He shouted for his old battery, Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery, to deploy on a small knoll east of the Brawner farmhouse. Soon, the ground trembled violently as Union and Confederate gunners exchanged fire. Within minutes, the Federal Regulars were getting the better of their Confederate counterparts and the Southerners elected to pull their guns back to safety. However, just as these guns fell back, Jackson sent in another battery, this time on Gibbon’s left, and it was quickly blasting case and solid shot at the Union battery.

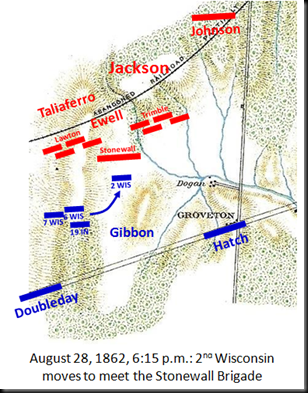

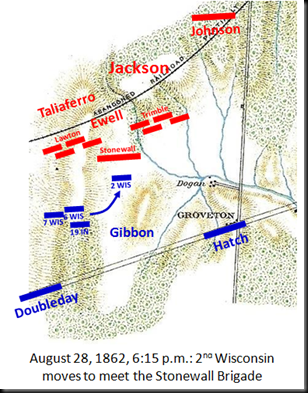

Gibbon quickly ordered the entire brigade off the road and north into the cover of the forest on the Brawner farm. At this moment, Gibbon could only assume that this was merely harassing fire from a few light horse batteries. He had no idea that Jackson’s entire force of 24,000 men lie just beyond the trees within a mile of his position. So, he decided to deal with the artillery and ordered the 2nd Wisconsin into line of battle. The regiment marched off up the hill, throwing skirmishers out in front as they approached the Brawner farmhouse. But as they closed the distance between themselves and the offending battery, they soon saw the sight of an entire Confederate infantry brigade emerging from the woods, colors flying and full of fight.

The brigade moving toward them was the already legendary Stonewall Brigade. Called Jackson’s “foot cavalry” because of the incredible distances they could travel in only days, these were arguably the best soldiers in Lee’s army. Veterans of every major battle fought in the East to date, the war had cut their numbers from 2,000 to only 800. But this 800 were tough, seasoned, hard fighters and, with the 2nd Wisconsin only numbering 430 men, Jackson’s men had them at almost a two to one advantage. Still, the sight of the Stonewall Brigade did not seem to deter the Wisconsin men, who continued to move up the hill towards them. As Charles King, who was a young lieutenant acting as an adjutant in Gibbon’s brigade, later wrote more than a little romantically, "Straight for the guns drives the daring blue line, backed by eight solid companies, closed on the colors and marching abreast. Fancy the canary defying the cat! Fancy the terrier bearding the tiger! Fancy the lamb assailing the butcher, and you have the sensation that thrills the waiting divisions as a grizzled Georgia colonel slaps down his field-glass and turns to his men with delight in his eye and five words on his tongue: ‘The Black Hats—by God!’”

The brigade moving toward them was the already legendary Stonewall Brigade. Called Jackson’s “foot cavalry” because of the incredible distances they could travel in only days, these were arguably the best soldiers in Lee’s army. Veterans of every major battle fought in the East to date, the war had cut their numbers from 2,000 to only 800. But this 800 were tough, seasoned, hard fighters and, with the 2nd Wisconsin only numbering 430 men, Jackson’s men had them at almost a two to one advantage. Still, the sight of the Stonewall Brigade did not seem to deter the Wisconsin men, who continued to move up the hill towards them. As Charles King, who was a young lieutenant acting as an adjutant in Gibbon’s brigade, later wrote more than a little romantically, "Straight for the guns drives the daring blue line, backed by eight solid companies, closed on the colors and marching abreast. Fancy the canary defying the cat! Fancy the terrier bearding the tiger! Fancy the lamb assailing the butcher, and you have the sensation that thrills the waiting divisions as a grizzled Georgia colonel slaps down his field-glass and turns to his men with delight in his eye and five words on his tongue: ‘The Black Hats—by God!’”

As the two groups closed to rifle range, one young Union soldier noted that his comrades “held their pieces with a tighter grasp” and began to murmur quietly, expressing their impatience with prosaic but determined language such as “Come on, God damn you.” At less than 100 yards, the 2nd Wisconsin unleashed what a Confederate officer remembered as “a most terrific and deadly fire.” The Virginians staggered and came to a halt in the face of the Federal volley.

As the two groups closed to rifle range, one young Union soldier noted that his comrades “held their pieces with a tighter grasp” and began to murmur quietly, expressing their impatience with prosaic but determined language such as “Come on, God damn you.” At less than 100 yards, the 2nd Wisconsin unleashed what a Confederate officer remembered as “a most terrific and deadly fire.” The Virginians staggered and came to a halt in the face of the Federal volley.

For the next 20 minutes, the two sides blasted away at one another, neither giving an inch, neither breaking for the rear. Soon, however, the Confederate numbers began to tell, as the Virginian’s line stretched and now threatened to overlap the 2nd Wisconsin’s left flank. Seeing this, Gibbon immediately ordered the 423 men of the 19th Indiana into position on the 2nd’s left. No sooner had the inexperienced Hoosier’s arrived than they were greeted by a thunderous volley issued from Jackson’s men. But, these green troops quickly steadied themselves and began to fire back as rapidly as the more experienced Wisconsin men next to them.

Things were not going according to Jackson’s plan and, as the light was fading, he urgently looked for more men to join the fight and push the impudent Yankees off the hillside. He soon encountered four regiments of Georgians under Alexander Lawton, numbering between 800 and 1,000 men, and personally led them to the fighting. Lawton’s regiments went into position on the Virginian’s left and now began to overlap the 2nd Wisconsin’s right flank. Gibbon responded by sending the 7th Wisconsin to in on the 2nd’s right, but these 440 men still were not enough to match the growing Confederate advantage in numbers. As the two sides continued to blaze away at one another, Union wounded began to steadily stream down the hillside toward field hospitals south of the pike. As it became darker, the rifle fire merged into what Gibbon described as a “long and continuous roll.” King wrote that, as the dim twilight deepened, “night and hell seem to come down together.”

Things were not going according to Jackson’s plan and, as the light was fading, he urgently looked for more men to join the fight and push the impudent Yankees off the hillside. He soon encountered four regiments of Georgians under Alexander Lawton, numbering between 800 and 1,000 men, and personally led them to the fighting. Lawton’s regiments went into position on the Virginian’s left and now began to overlap the 2nd Wisconsin’s right flank. Gibbon responded by sending the 7th Wisconsin to in on the 2nd’s right, but these 440 men still were not enough to match the growing Confederate advantage in numbers. As the two sides continued to blaze away at one another, Union wounded began to steadily stream down the hillside toward field hospitals south of the pike. As it became darker, the rifle fire merged into what Gibbon described as a “long and continuous roll.” King wrote that, as the dim twilight deepened, “night and hell seem to come down together.”

As the brutal fighting continued, Jackson became uncharacteristically more desperate. These Yankees were fighting with what he described later as “obstinate determination” and Jackson was not a man given to hyperbole. Therefore, he tried to get more men into the line and break the Federals once and for all. He dispatched Isaac Trimble’s 1,200-man brigade to form up on the Stonewall Brigade’s left, hoping to envelope Gibbon’s line and turn

As the brutal fighting continued, Jackson became uncharacteristically more desperate. These Yankees were fighting with what he described later as “obstinate determination” and Jackson was not a man given to hyperbole. Therefore, he tried to get more men into the line and break the Federals once and for all. He dispatched Isaac Trimble’s 1,200-man brigade to form up on the Stonewall Brigade’s left, hoping to envelope Gibbon’s line and turn  the Federal flank at last. However, as Trimble’s men approached their place in the line, they discovered that, once again, John Gibbon was ahead of Jackson. Gibbon had sent his last regiment, the 6th Wisconsin, forward into a dry streambed, lengthening his line to the right. At a range of only 75 yards, the 6th hammered Trimble with a volley that brought the Southern line to a complete and utterly stunned halt. One man from the 6th recalled, “Every gun cracked at once, and the line in front, which had faced us at the command ‘ready’ melted away, and instead of the heavy line of battle that was there before our volley, they presented the appearance of a skirmish line.”

the Federal flank at last. However, as Trimble’s men approached their place in the line, they discovered that, once again, John Gibbon was ahead of Jackson. Gibbon had sent his last regiment, the 6th Wisconsin, forward into a dry streambed, lengthening his line to the right. At a range of only 75 yards, the 6th hammered Trimble with a volley that brought the Southern line to a complete and utterly stunned halt. One man from the 6th recalled, “Every gun cracked at once, and the line in front, which had faced us at the command ‘ready’ melted away, and instead of the heavy line of battle that was there before our volley, they presented the appearance of a skirmish line.”

As the bloody work continued, Gibbon realized there was a 250-yard gap between the 7th and 6th Wisconsin. He urgently requested help from both Hatch and Patrick’s brigades, but none came. Luckily, however, General Abner Doubleday decided on his own initiative to send the 76th New York and 56th Pennsylvania from his brigade to Gibbon’s assistance. These fresh troops moved quickly to close the gap between the 7th and 6th Wisconsin, reinforcing Gibbon’s steadily dwindling line. In addition, their arrival brought Federal strength to just over 2,700 men, almost matching the 3,000 Jackson had been able to bring forward. However, while Jackson had easily another 20,000 men nearby, for some reason, he was unable to leverage this force, despite repeated attempts to do so. Therefore, the battle had now become a classic “soldier’s fight,” one in which the actions of individual units and the average soldier are more important in determining the outcome than whatever the original plan might have been.

As the bloody work continued, Gibbon realized there was a 250-yard gap between the 7th and 6th Wisconsin. He urgently requested help from both Hatch and Patrick’s brigades, but none came. Luckily, however, General Abner Doubleday decided on his own initiative to send the 76th New York and 56th Pennsylvania from his brigade to Gibbon’s assistance. These fresh troops moved quickly to close the gap between the 7th and 6th Wisconsin, reinforcing Gibbon’s steadily dwindling line. In addition, their arrival brought Federal strength to just over 2,700 men, almost matching the 3,000 Jackson had been able to bring forward. However, while Jackson had easily another 20,000 men nearby, for some reason, he was unable to leverage this force, despite repeated attempts to do so. Therefore, the battle had now become a classic “soldier’s fight,” one in which the actions of individual units and the average soldier are more important in determining the outcome than whatever the original plan might have been.

Jackson’s frustrations reached a peak around 7:00 p.m. and he decided to take the offensive, ordering all 3,000 men forward in an effort to crush all resistance. But, in an indication of the lack of command cohesion that seemed to plague all Jackson’s efforts at Brawner’s Farm, only a couple of Trimble’s regiments stepped forward to attack. They moved down the hillside at the double quick, with many men stumbling in chuckholes and falling over fence rails in the now increasing darkness. The two attacking regiments, the 21st Georgia and 21st North Carolina, received a devastating volley from the 56th Pennsylvania, while the 6th Wisconsin delivered an enfilading fire into the Confederate left flank. Within seconds, the attacking line seemed to melt into the ground, withered by the storm of lead loosed upon them. One 6th Wisconsin officer would remember that “human nature could not stand such a terrible wasting fire … it literally mowed out great gaps in the line.”

What one historian aptly described as a “whirlpool of death” consumed the 21st North Carolina and Georgia. As one Georgian would write years later, “The blazes from their guns seemed to pass through our ranks.” The 21st Georgia would lose 184 of 242 men that evening, a staggering 76 percent casualty rate. In fact, one company of the regiment went into the attack with 45 men, but only five returned unscathed.

What one historian aptly described as a “whirlpool of death” consumed the 21st North Carolina and Georgia. As one Georgian would write years later, “The blazes from their guns seemed to pass through our ranks.” The 21st Georgia would lose 184 of 242 men that evening, a staggering 76 percent casualty rate. In fact, one company of the regiment went into the attack with 45 men, but only five returned unscathed.

As Trimble’s assault ground to a complete halt, Jackson rode to General Lawton, whose brigade of Georgians were now near the center of the line, and ordered him forward. But, within minutes, Lawton’s men met a fate similar to Trimble’s, as the 7th Wisconsin and 76th New York wheeled from their positions to deliver a crushing volley into the Southern flank. One of Lawton’s regiments would sustain 74 percent casualties and the survivors from all the attacking regiments quickly fell back to their original positions.

It was now approaching 8:00 p.m. and darkness totally enveloped the fields around the Brawner farmhouse. Neither side pulled back and the firing continued, with some portions of the lines separated by less than 30 yards. No one on either side could see the other and all they could do was fire a the telltale muzzle flashes that indicated where an opponent might be crouched. Years later a Union veteran of Brawner’s Farm recalled, “The two crowds, they could hardly be called lines, were within, it seemed to me, fifty yards of each other, and were pouring musketry into each other as rapidly as men could load and shoot.” Still, neither side would yield the ground they had held so preciously over the course of the last two bloody hours. Soon, however, the rifle fire gradually slackened and faded, only to be replaced by the pathetic cries of the wounded. Each side now ventured forward with lamps held high, collecting the dead and wounded. The Battle of Brawner’s Farm was over.

The losses on both sides were frightful. Gibbon’s brigade lost almost 800 killed or wounded. The 2nd Wisconsin lost 276 men out of the 430 who went into the line and 21 of their wounded were hit at least twice. On the other side, in addition to Lawton and Trimble’s horrific losses, the Stonewall brigade had lost 340 men out of 800, a 40 percent casualty rate. In fact, so fierce was the fighting in those two hours along the Warrenton Pike, that one in every three men engaged was hit at least once. As Gibbon surveyed the damage to  his command, Colonel William Robinson, commander of the 7th Wisconsin rode up to him. Obviously feeling that Gibbon had been a harsh taskmaster in training the brigade and that the West Pointer had not previously come to respect his men, the fiery, dark-eyed Robinson looked Gibbon in the eye and said, “What do you think of the Seventh now?” As Gibbon reached out to him and before he could tell Robinson how well his men had fought, Robinson’s eyes rolled back, and he fell from his horse. Gibbon called for a surgeon, dismounted, and knelt next to Robinson, only to find that he had been shot through both thighs, his boots filled with his own blood. Despite what must have agonizing pain and a severe loss of blood, Robinson had led his men throughout the battle and now was overcome only after he had reported to Gibbon and demanded his men’s bravery and skill be acknowledged.

his command, Colonel William Robinson, commander of the 7th Wisconsin rode up to him. Obviously feeling that Gibbon had been a harsh taskmaster in training the brigade and that the West Pointer had not previously come to respect his men, the fiery, dark-eyed Robinson looked Gibbon in the eye and said, “What do you think of the Seventh now?” As Gibbon reached out to him and before he could tell Robinson how well his men had fought, Robinson’s eyes rolled back, and he fell from his horse. Gibbon called for a surgeon, dismounted, and knelt next to Robinson, only to find that he had been shot through both thighs, his boots filled with his own blood. Despite what must have agonizing pain and a severe loss of blood, Robinson had led his men throughout the battle and now was overcome only after he had reported to Gibbon and demanded his men’s bravery and skill be acknowledged.

For John Gibbon, his men’s bravery would be wasted, as John Pope’s complete mismanagement led to a signal defeat at the hands of Robert Lee in the Battle of Second Manassas. Still, however, notice had been served upon Stonewall Jackson, the Army of Northern Virginia, and history itself that these men from Wisconsin and Indiana were the best brigade in the Union Army. The Black Hat Brigade’s magnificent performance at Brawner’s Farm would be repeated many times, earning them another name, one they will own for all time: The Iron Brigade.

They say a journey begins with 1,000 words and yet, within the first few words read, you have my full attention. Each post, each subject that you choose, is read as if I am, for the first time, taking a journey down the same path as the subjects as well as the author. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteI am under contract and writing about the 19th Indiana. This has helped me enormously in seeing the battle at Brawner's Farm clearly so that I can write about the 19th's part in it far better than I could have 10 minutes ago. My thanks to you.

ReplyDelete