I have written about Gettysburg in several other blog entries and, as we approach the 146th anniversary of this epic battle, I thought I might do a series of essays on the three-days of fighting in Pennsylvania. As I said in an earlier essay, Gettysburg seems to stand alone among Civil War battles in the collective and popular historical memory of the American people. If the Civil War was America’s “Iliad,” Gettysburg is perceived as our Troy, a titanic struggle that determined the nation’s fate.

Like many historians, I do not see the battle as the ultimate turning point of the war, although, had things gone differently, it might well have been a shattering defeat for the Union, and one from which they might never have recovered. Still, however, Gettysburg holds a tremendous fascination, even for the most jaundiced of Civil War historians. I think that is because this battle, perhaps above all others, so strongly reflects the human element of warfare. There were good command decisions and bad ones, and these are still the topic of great debate. Further, there was the incredible tenacity of the common soldier, where, despite command decisions, the battle simply came down to fierce combat among soldiers; a battle where the plans and decisions of generals mattered little because the struggle became purely a “soldier’s fights.” Finally, there is also the element of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Lincoln chose this one battle to symbolize the nature of the war and its ultimate goal of a “new birth of freedom,” forever cementing Gettysburg’s place in American culture.

As the Gettysburg campaign unfolded in June 1863, the two opposing armies and their commanders were a study in contrast. Two years of war and, especially, the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville in May 1863, had resulted in two armies that seemed, on the surface at least, to be going in opposite directions. The differences were not so much those dictated by numbers of available combatants or by equipment because, by the time the two armies met in Pennsylvania, both were remarkably equivalent in those aspects of relative military strength. Instead, the differences were all closely related and were based upon morale, psychology, and, perhaps most importantly, perception. As such, they would impact the opening days of the campaign as well as its eventual outcome.

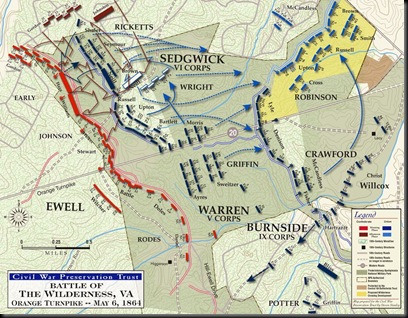

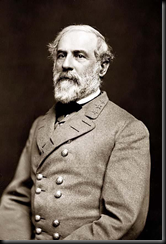

The aftermath of the Battle of Chancellorsville found the Army of Northern Virginia slightly bruised and battered but with its morale high, supremely confidant in themselves and their leaders. While the loss of General Stonewall Jackson had been painful, the results of the battle gave them an even more unshakable faith in their commander, Robert E. Lee. At Chancellorsville, Lee committed a military sin when he, first, divided his army in the face of a superior enemy, assaulting him on two fronts. He then compounded his “sin” by further dividing his force in order to have Jackson march through the tangled terrain of the Wilderness to attack the Army of the Potomac on its exposed right flank. The result was a stunning victory and, in the minds of his men, Lee was a master who could lead them to victory anywhere, anytime.

The aftermath of the Battle of Chancellorsville found the Army of Northern Virginia slightly bruised and battered but with its morale high, supremely confidant in themselves and their leaders. While the loss of General Stonewall Jackson had been painful, the results of the battle gave them an even more unshakable faith in their commander, Robert E. Lee. At Chancellorsville, Lee committed a military sin when he, first, divided his army in the face of a superior enemy, assaulting him on two fronts. He then compounded his “sin” by further dividing his force in order to have Jackson march through the tangled terrain of the Wilderness to attack the Army of the Potomac on its exposed right flank. The result was a stunning victory and, in the minds of his men, Lee was a master who could lead them to victory anywhere, anytime.

For his part, Lee seemed to believe his army and his beloved men could do anything. Eight months previously, they had performed spectacularly in his Maryland campaign, where he pushed them almost to the breaking point with forced marches, and, at Chancellorsville, they had again done whatever he asked, even when it seemed impossible. The adoration between the soldiers and their general was mutual, complete, and, perhaps, dangerously so. In many soldiers’ minds, Lee could do no wrong and their opponent was seen as weak and unworthy. At the same time, in Lee’s mind, his faith in his army’s ability to do the impossible may have reached a point where his military judgment and strategic and tactical decision-making were actually clouded by excessive confidence and unrealistic expectations.

For his part, Lee seemed to believe his army and his beloved men could do anything. Eight months previously, they had performed spectacularly in his Maryland campaign, where he pushed them almost to the breaking point with forced marches, and, at Chancellorsville, they had again done whatever he asked, even when it seemed impossible. The adoration between the soldiers and their general was mutual, complete, and, perhaps, dangerously so. In many soldiers’ minds, Lee could do no wrong and their opponent was seen as weak and unworthy. At the same time, in Lee’s mind, his faith in his army’s ability to do the impossible may have reached a point where his military judgment and strategic and tactical decision-making were actually clouded by excessive confidence and unrealistic expectations.

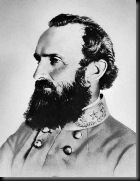

At the same time, all was not well in the command structure of the Army of Northern Virginia. The loss of Stonewall Jackson was deep in a very real and military sense, perhaps more so than anyone truly realized at the time. Jackson was eccentric, aggressive, and, at times, even brilliant in the field. For Lee, who clearly favored bold tactics and a “hit them hard” approach, Jackson was the favored executor of those tactics and his right arm. Now, that important element was gone.

At the same time, all was not well in the command structure of the Army of Northern Virginia. The loss of Stonewall Jackson was deep in a very real and military sense, perhaps more so than anyone truly realized at the time. Jackson was eccentric, aggressive, and, at times, even brilliant in the field. For Lee, who clearly favored bold tactics and a “hit them hard” approach, Jackson was the favored executor of those tactics and his right arm. Now, that important element was gone.

In the wake of Jackson’s loss, Lee was left with General James Longstreet, the steady but cautious commander of the First Corps, and a collection of other officers who, while seemingly competent, had never commanded a corps and were certainly not as brilliantly aggressive as Jackson. Plus, the two corps that made up the Army of Northern Virginia were larger than usual for the era. Therefore, Lee decided to reorganize the army into three corps of three divisions each and assigned them Generals Longstreet, Ewell, and A.P. Hill, respectively. Ewell and Hill had proven to be able division commanders, but now they would be asked to command a corps in a major campaign.

In the wake of Jackson’s loss, Lee was left with General James Longstreet, the steady but cautious commander of the First Corps, and a collection of other officers who, while seemingly competent, had never commanded a corps and were certainly not as brilliantly aggressive as Jackson. Plus, the two corps that made up the Army of Northern Virginia were larger than usual for the era. Therefore, Lee decided to reorganize the army into three corps of three divisions each and assigned them Generals Longstreet, Ewell, and A.P. Hill, respectively. Ewell and Hill had proven to be able division commanders, but now they would be asked to command a corps in a major campaign.  Further, it is important to note that Confederate losses in terms of officers and, in particular, regiment commanders had been high at Chancellorsville. This, combined with Lee’s reorganization, resulted in a command structure that was filled with new faces from top to bottom. Therefore, as the Army of Northern Virginia prepared to move north, it was reorganized, had many new commanders, but was reasonably well equipped, and, most of all, it was very confident.

Further, it is important to note that Confederate losses in terms of officers and, in particular, regiment commanders had been high at Chancellorsville. This, combined with Lee’s reorganization, resulted in a command structure that was filled with new faces from top to bottom. Therefore, as the Army of Northern Virginia prepared to move north, it was reorganized, had many new commanders, but was reasonably well equipped, and, most of all, it was very confident.  As historian Edwin Coddington points out, it had become “convinced of its invincibility,” and had developed “the attitude that breeds overconfidence, which in turn leads to mistakes when the foe proves worthy of his mettle.”

As historian Edwin Coddington points out, it had become “convinced of its invincibility,” and had developed “the attitude that breeds overconfidence, which in turn leads to mistakes when the foe proves worthy of his mettle.”

That foe, meanwhile, was something of a contrast with the Army of Northern Virginia in the days following Chancellorsville. The men of the Army of the Potomac were confident in themselves as soldiers, and their commanding officers from the regiment to corps level knew their men could fight and fight well. They were well-fed, well-trained, and well-equipped. The men had shown themselves to be hardy, brave, and even courageous fighters. But neither the men nor most of their immediate commanders had any faith or confidence in their commanding general, Joseph Hooker.

For the Chancellorsville campaign, Hooker had devised a brilliant turning maneuver that he and his army executed flawlessly. However, when the fighting began, the usually exuberant and flamboyant Hooker became fearful, cautious, and completely unable to effectively command the army. Essentially, Hooker suffered from an inability to fight a battle “on the map.” In other words, while he had proven himself to be an able tactical commander in the field at the division and corps level, where he could see all his men and see the enemy, he could not seem to command an entire army spread across a larger area where he physically could not see them. Plus, as the battle unfolded, he became gripped with a fear of failure. Finally, when his opponent, Robert E. Lee, did not behave as planned and responded with unconventional tactics, Hooker not only froze, he panicked. Even after his army had been flanked and the XI Corps sent reeling from Jackson’s sudden attack on the right flank, Hooker’s force was still intact and capable of punishing the enemy. But, Hooker did not seem to know how to adapt his plan, regroup, and regain the initiative he had surrendered. Therefore, he elected to withdraw and add another defeat to the growing list of losses for the Army of the Potomac.

For the Chancellorsville campaign, Hooker had devised a brilliant turning maneuver that he and his army executed flawlessly. However, when the fighting began, the usually exuberant and flamboyant Hooker became fearful, cautious, and completely unable to effectively command the army. Essentially, Hooker suffered from an inability to fight a battle “on the map.” In other words, while he had proven himself to be an able tactical commander in the field at the division and corps level, where he could see all his men and see the enemy, he could not seem to command an entire army spread across a larger area where he physically could not see them. Plus, as the battle unfolded, he became gripped with a fear of failure. Finally, when his opponent, Robert E. Lee, did not behave as planned and responded with unconventional tactics, Hooker not only froze, he panicked. Even after his army had been flanked and the XI Corps sent reeling from Jackson’s sudden attack on the right flank, Hooker’s force was still intact and capable of punishing the enemy. But, Hooker did not seem to know how to adapt his plan, regroup, and regain the initiative he had surrendered. Therefore, he elected to withdraw and add another defeat to the growing list of losses for the Army of the Potomac.

As Lee planned and organized for his campaign, Hooker did little planning and simply went into a reactive posture, which remained the case until he resigned from command weeks later. In addition, the only major change he made organizationally involved the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. Prior to Chancellorsville, Hooker placed the cavalry into an independent corps. This would allow them to be commanded by a cavalry officer and, hopefully, to be used far more effectively. However, he was still disappointed in how that arm had performed during the campaign and, he relieved General George Stoneman of command, dispersing some of his key lieutenants, such as General William Averell, to other commands outside the Army of the Potomac. In his place, Hooker appointed General Alfred Pleasanton based solely on seniority, which was a procedural problem that had long plagued the Union armies. General John Buford, a talented, seasoned cavalry veteran, was probably a better choice than Pleasanton, but he lacked seniority by a mere eleven days.  This too, however, would prove to be somewhat providential for the Union forces since Buford, who would now commanded the 1st Division of the Cavalry Corps, would perform brilliantly in the coming campaign and play a crucial tactical role in the early hours of the fighting at Gettysburg.

This too, however, would prove to be somewhat providential for the Union forces since Buford, who would now commanded the 1st Division of the Cavalry Corps, would perform brilliantly in the coming campaign and play a crucial tactical role in the early hours of the fighting at Gettysburg.

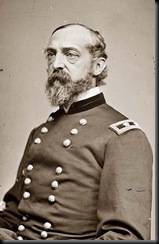

The commanders of Hooker’s infantry corps, meanwhile, were a mixed bag. Overall, however, they were a solid group. George Meade, commanding V Corps, was competent, reliable, and steady, as was  John Sedgwick, who led VI Corps. John Reynolds and Winfield Scott Hancock, who commanded I and II Corps, respectively, were both men who shared a talent for tactics that bordered on the brilliant. They also were men who had the ability to inspire all around them when under fire, especially Hancock. Unfortunately, after these four officers, there was a steep drop in talent.

John Sedgwick, who led VI Corps. John Reynolds and Winfield Scott Hancock, who commanded I and II Corps, respectively, were both men who shared a talent for tactics that bordered on the brilliant. They also were men who had the ability to inspire all around them when under fire, especially Hancock. Unfortunately, after these four officers, there was a steep drop in talent.  General Oliver Howard of XI Corps and Henry Slocum of XII were both very ordinary as corps commanders. Plus, Howard carried the stigma of having had his corps break and run under the onslaught of Jackson’s flanking attack at Chancellorsville and, as a result, his men, many of whom were of German origin, earned the dubious nickname of being the “Flying Dutchmen.” Finally, there was General Daniel Sickles, commander of III Corps.

General Oliver Howard of XI Corps and Henry Slocum of XII were both very ordinary as corps commanders. Plus, Howard carried the stigma of having had his corps break and run under the onslaught of Jackson’s flanking attack at Chancellorsville and, as a result, his men, many of whom were of German origin, earned the dubious nickname of being the “Flying Dutchmen.” Finally, there was General Daniel Sickles, commander of III Corps.  Sickles was a New York politician, a Democrat, and a man seemingly without any military talents except his personal bravery. Other than that, he specialized in conspiracy, cronyism, and always making sure his mistakes could be blamed on the failures of another officer. His sole claim to fame was that he murdered his wife’s lover and, in the ensuing trial, became the first man in American history that was cleared because he found to be temporarily insane.

Sickles was a New York politician, a Democrat, and a man seemingly without any military talents except his personal bravery. Other than that, he specialized in conspiracy, cronyism, and always making sure his mistakes could be blamed on the failures of another officer. His sole claim to fame was that he murdered his wife’s lover and, in the ensuing trial, became the first man in American history that was cleared because he found to be temporarily insane.

All in all, the Army of the Potomac was actually a first class fighting machine. While their morale was low following Chancellorsville, the fighting ability of its officers and men was unquestioned. They merely needed the leadership of a good commander to bring them victory and make them the great army they were waiting to become. As Coddington points out, “To call them hirelings, foreign mercenaries, scum of the cities, and the poorer classes of the country, terms used in derision and contempt by the Southern press and some Confederate officers, reveals a fatal delusion.”

Even before the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, Robert E. Lee had wanted to take the offensive and seize the initiative before Hooker could mount a summer campaign. However, Hooker was able to briefly throw Lee’s plans off track when he moved his army against Lee at Chancellorsville. Lee, therefore, temporarily postponed his plans to deal with Hooker and, following the defeat of the Union forces, he again resumed his plans for an offensive. For this summer campaign, Lee proposed a new invasion of the North. In many ways, his goals for the campaign were similar to those he espoused in 1862 following his defeat of Union’s Army of Virginia at Second Manassas. First, by moving north across the Potomac, he could get the Army of the Potomac out of Virginia. This would remove the immediate danger to Richmond, and allow Virginia’s farmers to harvest their crops unmolested by Federal forces, enabling them to provide those crops to Lee’s army. Second, by going north, Lee could also strip Maryland and Pennsylvania of much needed food and supplies for his army. Third, Lee could also maneuver so as to keep the Army of the Potomac off balance and, while hopefully avoiding a general engagement, fight it and defeat it piecemeal. This, Lee predicted, might gain political advantage to the Peace Democrats in the North and force a negotiated end to the war on Southern terms.

While all these reasons for the campaign were virtually identical to those he used in 1862, he added one more. Lee defended his plans to President Davis by reasoning that, if he could threaten Philadelphia, Baltimore, and, especially, Washington, the Lincoln administration would be forced to withdraw forces from the West to defend against attack, thus lessening Grant’s stranglehold on Vicksburg. In all likelihood, this argument was as insincere as it was illogical. Throughout the war, Lee repeatedly demonstrated that he either did not understood or cared little for any aspect of the war outside of Virginia. However, he was probably politically astute enough to know how much the fate of Vicksburg meant to Jefferson Davis. While in hindsight it would seem unlikely that anything Lee did would influence Grant’s operations around Vicksburg, Davis was probably ready to grasp at any straw that might save that key city from capture. While there was some initial political maneuvering and misunderstanding of Lee’s objectives, Davis finally gave his consent to Lee’s plan.

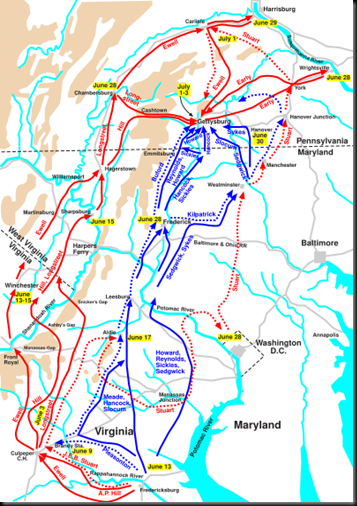

Lee’s plans for the movement of his army were both sound and relatively simple. He would quietly disengage from the Union forces at his front along the Rappahannock River, and then move his army down the Shenandoah Valley, keeping the Blue Ridge Mountains between himself and Hooker’s army. Using J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry to screen his movements and keep the passes into the Shenandoah blocked, he would move steadily northward and cross the Potomac into Maryland before proceeding into Pennsylvania. Finally, when Hooker actually realized what was happening, Lee would be far to the north, maneuvering at will, raising havoc, and threatening the Federal capitol.

Lee’s plans for the movement of his army were both sound and relatively simple. He would quietly disengage from the Union forces at his front along the Rappahannock River, and then move his army down the Shenandoah Valley, keeping the Blue Ridge Mountains between himself and Hooker’s army. Using J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry to screen his movements and keep the passes into the Shenandoah blocked, he would move steadily northward and cross the Potomac into Maryland before proceeding into Pennsylvania. Finally, when Hooker actually realized what was happening, Lee would be far to the north, maneuvering at will, raising havoc, and threatening the Federal capitol.

For his part, Hooker seemingly did not have a strategy except to be reactive. He had surrendered the initiative to Lee at Chancellorsville and had no plans to recapture it. When his intelligence indicated movements by the Confederate forces, he was unsure what to make of them. At first, he thought perhaps Stuart was going to attempt another large cavalry raid on the Federal rear. To counter that possibility, he ordered General Pleasanton to take his cavalry, along with some supporting infantry, and attack Stuart’s forces in the Culpeper area. This led to the battle at Brandy Station, which, while it did not break up Stuart’s forces, demonstrated that the Federal cavalry was gaining on its Southern foe in quality and fighting abilities.

For his part, Hooker seemingly did not have a strategy except to be reactive. He had surrendered the initiative to Lee at Chancellorsville and had no plans to recapture it. When his intelligence indicated movements by the Confederate forces, he was unsure what to make of them. At first, he thought perhaps Stuart was going to attempt another large cavalry raid on the Federal rear. To counter that possibility, he ordered General Pleasanton to take his cavalry, along with some supporting infantry, and attack Stuart’s forces in the Culpeper area. This led to the battle at Brandy Station, which, while it did not break up Stuart’s forces, demonstrated that the Federal cavalry was gaining on its Southern foe in quality and fighting abilities.

As evidence mounted indicating there was more happening here than a mere cavalry raid, Hooker seemed unable to properly analyze his opponent’s actions and formulate a countermove. Even when he seemingly knew Lee’s army was stretched vulnerably along the Shenandoah Valley, he proposed that he attack Lee’s remaining forces at Fredericksburg and thus threaten the Confederate capitol at Richmond. President Lincoln turned this idea down without hesitation and there ensued a continuous series of harsh, combative communications between Hooker and Lincoln, Secretary of War Stanton, and General Halleck. Lincoln urged an attack on Lee’s exposed army as it transited the Shenandoah, but it was to no avail. Hooker was more concerned about again being made the fool in Lee’s game than in countering his opponent’s thrust into the North. Hooker was paralyzed by a fear of what Lee might do. He was so concerned that Lee might again do something unconventional, he could apparently do nothing but attempt to shadow his enemy and move roughly parallel to him.

Even in this, Hooker failed. He grossly underestimated Lee’s rate of movement and soon discovered Lee was already across the Potomac and into northern Maryland. To his credit, however, Hooker did react properly to this threat. He hurried the Army of the Potomac northward with grueling forced marches. In addition, he positioned the army well and placed it such that it could react to any potential move by Lee’s army, and still cover both Washington and Baltimore.

While Hooker was trying to shadow Lee’s army, Lee made his initial error of the campaign by issuing a somewhat unclear order to General Stuart. Lee told Stuart that, if there was no enemy threat at his front, he was to take three of his brigades and move across the Potomac. Then, he was to place himself on Ewell’s right in order to guard the infantry’s flank, watch for enemy movements, and gather supplies. However, the orders offered Stuart some latitude and did not make clear the precise intent of Stuart’s eventual position on Ewell’s right. Unfortunately for Lee, Stuart was the kind of officer who preferred to operate somewhat independently.

While Hooker was trying to shadow Lee’s army, Lee made his initial error of the campaign by issuing a somewhat unclear order to General Stuart. Lee told Stuart that, if there was no enemy threat at his front, he was to take three of his brigades and move across the Potomac. Then, he was to place himself on Ewell’s right in order to guard the infantry’s flank, watch for enemy movements, and gather supplies. However, the orders offered Stuart some latitude and did not make clear the precise intent of Stuart’s eventual position on Ewell’s right. Unfortunately for Lee, Stuart was the kind of officer who preferred to operate somewhat independently.

In addition, Lee trusted Stuart’s judgment, which is surprising given that Stuart had failed him on his first invasion of the North in 1862. At that time, Stuart and his command were too busy enjoying the Maryland countryside to monitor McClellan’s movements properly. The result was that Lee, with his army divided, suddenly found the Federal army he assumed to be disorganized and licking its wounds inside the defenses of Washington was, in fact, pressing down on him and placing his army in grave peril. One of the criticisms of Lee has been that he had his favorites and that he failed to properly assess responsibility for what were sometimes grave errors and lapses in judgment. Such was the case with Stuart.

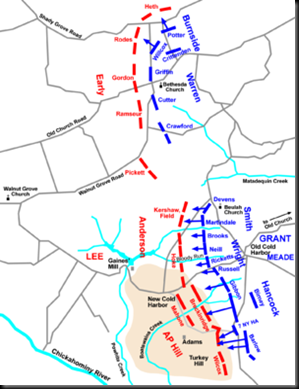

Rather than perceiving the true intent of Lee’s orders, Stuart instead decided to stage a grand raid and ride completely around the Army of the Potomac. This raid, which garnered headlines in the Northern press, was primarily a nuisance to the Federals. Worse, with Stuart out of touch, Lee had no intelligence on the movements of the Army of the Potomac. Late on June 28, with his army spread from Carlisle to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Lee found out through a spy that, not only was the Federal army not still in Virginia, it was, in fact, rapidly approaching Frederick, Maryland. Lee compounded Stuart’s error by not making use of the cavalry he still had on hand to either gather intelligence or screen his army from Federal cavalry. However, when Lee found out the true position of the Army of the Potomac, he began to regroup his forces and move to consolidate them in the face of the newly discovered threat.

Meanwhile, command of the Army of the Potomac was in turmoil. Hooker, who had been engaged in a running argument with General Halleck over the need to defend Harper’s Ferry, decided to pay a visit to that garrison on June 27 to determine the situation for himself, firsthand. While there, he and Halleck again exchanged bitter telegrams over the need to defend Harpers Ferry. Suddenly, in one of them, Hooker offered his resignation, stating he could not cover both Harpers Ferry and Washington with the forces at his disposal. Lincoln jumped at the offer and, perhaps much to Hooker’s surprise, accepted Hooker’s resignation.

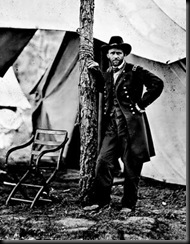

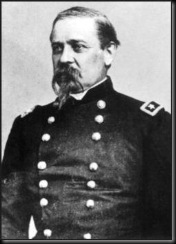

Within hours, orders from Halleck were delivered to General Meade offering him command of the Army of the Potomac. Meade accepted and immediately began to direct the army’s activities. One of the key elements of Halleck’s instructions to Meade was that he could assign any officer to a post for which he deemed him the best qualified, no matter the seniority of other officers. Meade would make excellent use of this authority during the coming days and it proved to be vital. Meade immediately adjusted the position of the army based on the intelligence he was receiving. He correctly concluded that his greatest threat from Lee was from the left. Therefore, he elected to give command of the left wing of the army and the three corps that comprised it to the very able John Reynolds. Throughout the days leading to the battle, Meade kept a continuous flow of information going to his corps commanders, telling them both what was happening as well as what he expected of them.

Within hours, orders from Halleck were delivered to General Meade offering him command of the Army of the Potomac. Meade accepted and immediately began to direct the army’s activities. One of the key elements of Halleck’s instructions to Meade was that he could assign any officer to a post for which he deemed him the best qualified, no matter the seniority of other officers. Meade would make excellent use of this authority during the coming days and it proved to be vital. Meade immediately adjusted the position of the army based on the intelligence he was receiving. He correctly concluded that his greatest threat from Lee was from the left. Therefore, he elected to give command of the left wing of the army and the three corps that comprised it to the very able John Reynolds. Throughout the days leading to the battle, Meade kept a continuous flow of information going to his corps commanders, telling them both what was happening as well as what he expected of them.

Being the cautious and thorough officer that he was, Meade also made contingency plans should he find the need to fall back to a strong defensive position. His engineers found good terrain for such a contingency along Pipe Creek and he issued a circular informing his commanders of the plan. This circular was later misunderstood and used as evidence against Meade by those who alledged that he was overly timid and not sufficiently aggressive. In retrospect, Meade probably should not have disseminated the order so broadly, but he was apparently a strong believer in open communications with his commanders. But, as John Ropes, the distinguished military historian, put it, “In all this, it seems to me that Meade acted with great prudence, and with sufficient boldness.”

As Lee began to consolidate his army in the Gettysburg vicinity, the excellent work of the Federal cavalry came to the forefront. Throughout the campaign, they had done a yeoman’s job of providing intelligence on Lee’s movements, although, at times, General Pleasanton misinterpreted the data when forwarding it. As Meade moved forward, the best information came from John Buford. His reports were always clear, concise, and unambiguous. Luckily for Meade and the Army of the Potomac, Pleasanton had assigned Buford and two of his brigades to cover Reynold’s flank as he moved in the general direction of Gettysburg. This meant that two of Meade’s best were working on the army’s left, where it would soon matter most.

As the opening phase of this great campaign ended, Lee’s army was moving to consolidate against a foe they only knew was nearby, while Meade’s army cautiously positioned itself to engage Lee once the situation dictated. The former was groping in relative darkness, blinded by a lack of intelligence, trying to ensure it was ready once the Federal army’s position became apparent, while the latter was seeking out their opponent, probing and preparing methodically. Both armies were roughly equivalent in strength, and both had seen some turmoil in command and organization. They had moved north stretched out, but now they were consolidating like two great snakes coiling to strike. One army, Lee’s, had long been the defender of its home soil, but now was the invader, while Meade’s army now found themselves defending Union soil for only the second time in the war. All the elements of a historic and inevitable clash were in place, and soon that fight would come.