Without question, The Gettysburg Address is one of the most famous speeches in American history. Children recite in school, or at least they used to, and many of its passages are instantly recognized by many Americans. But, I would venture to say that most people do not truly understand its importance or, more importantly, even begin to sense the magnificence and power of Abraham Lincoln’s 269 word oration. It has inspired much historiography, most notably the recent work of Garry Wills and Gabor Boritt.

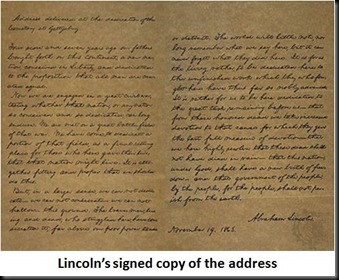

Every word, every nuance, has been examined and the speech has even inspired many myths. One myth holds that the speech was allegedly written on the back of an envelope, while another states that the address was considered a failure by the audience, the press, and Lincoln himself. The envelope myth has most certainly been debunked by historians and, in fact, no one is precisely sure what copy was the actual text as spoken on November 19, 1863, given that there are five different written versions. However, only one copy was actually signed by Lincoln and, while it was written down several months after the address, that is the version most of us are familiar with. As for its popularity at the time, most recollections simply state that the audience was surprised by the brevity of the speech and the press primarily divided their opinions along political lines. As for Lincoln himself, most recent scholarship seems to indicate that he felt his point had been delivered.

Every word, every nuance, has been examined and the speech has even inspired many myths. One myth holds that the speech was allegedly written on the back of an envelope, while another states that the address was considered a failure by the audience, the press, and Lincoln himself. The envelope myth has most certainly been debunked by historians and, in fact, no one is precisely sure what copy was the actual text as spoken on November 19, 1863, given that there are five different written versions. However, only one copy was actually signed by Lincoln and, while it was written down several months after the address, that is the version most of us are familiar with. As for its popularity at the time, most recollections simply state that the audience was surprised by the brevity of the speech and the press primarily divided their opinions along political lines. As for Lincoln himself, most recent scholarship seems to indicate that he felt his point had been delivered.

So, what was Lincoln’s point? While I cannot write a book here and provide the detailed analysis that men like Wills and Boritt already have, I will try to give you my views and do so as simply as possible. To do so, however, it is important to place the speech in context, both in terms of the war and the place it was delivered.

So, what was Lincoln’s point? While I cannot write a book here and provide the detailed analysis that men like Wills and Boritt already have, I will try to give you my views and do so as simply as possible. To do so, however, it is important to place the speech in context, both in terms of the war and the place it was delivered.

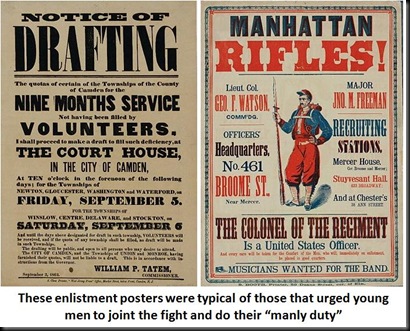

As for the war, in November 1863, the conflict was in the midst of its third full year. The previous summer, Union armies had been victorious both at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. But the fall had brought defeat at Chickamauga, which placed the defeated Union Army of the Cumberland under siege in Chattanooga. However, as Lincoln delivered his address at Gettysburg, the newly assigned Union commander in the West, Ulysses S. Grant, was preparing to break that siege, opening the door to the Deep South.

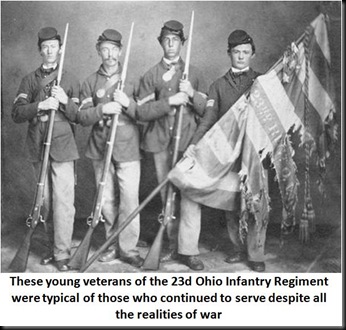

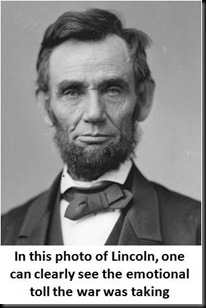

Still, the coming spring and summer would bring new campaigns, new battles, and ever more casualties. The war had already resulted in death and suffering on a scale the nation had never imagined possible, and Lincoln carried that great burden on his shoulders. His photographs from this time show deep lines on his face and one can sense his own intense suffering. He visited the hospitals in Washington D.C. constantly and saw firsthand the damage the war levied in broken bodies and souls. The nation was becoming war weary and the months ahead would not bring a swift end to the country’s pain. But, while Lincoln felt every bit of that pain, he also was keenly aware of what he called the “awful arithmetic of war.” He had not and would not lose his resolve to see the war through.

Still, the coming spring and summer would bring new campaigns, new battles, and ever more casualties. The war had already resulted in death and suffering on a scale the nation had never imagined possible, and Lincoln carried that great burden on his shoulders. His photographs from this time show deep lines on his face and one can sense his own intense suffering. He visited the hospitals in Washington D.C. constantly and saw firsthand the damage the war levied in broken bodies and souls. The nation was becoming war weary and the months ahead would not bring a swift end to the country’s pain. But, while Lincoln felt every bit of that pain, he also was keenly aware of what he called the “awful arithmetic of war.” He had not and would not lose his resolve to see the war through.

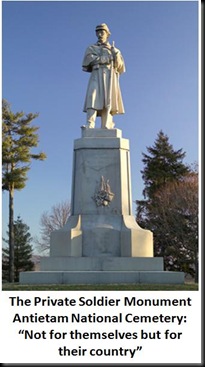

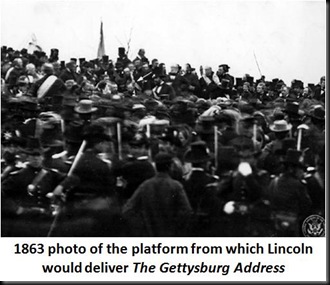

As for the place of the address, Gettysburg, of course, had been the site of the monumental three-day battle between the Union Army of the Potomac and Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Following the battle, it was decided to place a military cemetery on the battlefield where the remains of Unions soldiers killed in the fighting would be interred. The President, along with former Massachusetts senator and noted orator, Edward Everett, were invited to the dedication ceremonies. Everett, however, was to deliver the main dedication oration, while Lincoln was only to provide a “few appropriate remarks.” Everett’s two-hour oration, a length typical for mid-19th century speechmaking, clearly focused on what was likely his and the audience’s vision of the battle as a monumental turning point, a great signal victory. And, while Lincoln certainly said nothing to indicate he felt otherwise, we know that he did not share that view. He was, of course, grateful that General Meade and his army had turned Lee back, but he saw the battle as a lost opportunity to destroy Lee’s army and thus hasten the war’s conclusion. In his mind, Lee and his formidable army were still safe, lying in wait in northern Virginia. Bringing them to bay would require even more bloodshed and sacrifice. I raise this issue solely for one reason: While Gettysburg was the place for this address, on that November day he could have and, likely, would have given the same speech at any battlefield of the war.

As for the place of the address, Gettysburg, of course, had been the site of the monumental three-day battle between the Union Army of the Potomac and Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Following the battle, it was decided to place a military cemetery on the battlefield where the remains of Unions soldiers killed in the fighting would be interred. The President, along with former Massachusetts senator and noted orator, Edward Everett, were invited to the dedication ceremonies. Everett, however, was to deliver the main dedication oration, while Lincoln was only to provide a “few appropriate remarks.” Everett’s two-hour oration, a length typical for mid-19th century speechmaking, clearly focused on what was likely his and the audience’s vision of the battle as a monumental turning point, a great signal victory. And, while Lincoln certainly said nothing to indicate he felt otherwise, we know that he did not share that view. He was, of course, grateful that General Meade and his army had turned Lee back, but he saw the battle as a lost opportunity to destroy Lee’s army and thus hasten the war’s conclusion. In his mind, Lee and his formidable army were still safe, lying in wait in northern Virginia. Bringing them to bay would require even more bloodshed and sacrifice. I raise this issue solely for one reason: While Gettysburg was the place for this address, on that November day he could have and, likely, would have given the same speech at any battlefield of the war.

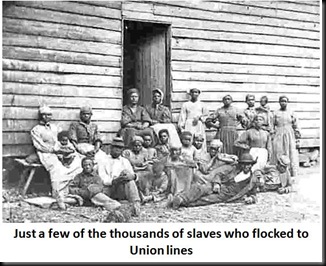

That brings us to the purpose and the meaning of his words. Lincoln begins with a simple summation of what he saw as the basis of the war. First, he reminds us that the nation was created as one where all men were to be equal. This is important to note because, here, he is really citing the Declaration of Independence, which he viewed as our “moral manifesto,” as the rock upon which the nation rested. The war, in turn, was testing whether a nation “so conceived and dedicated” could survive against those who challenged its very moral basis. Interestingly, however, Lincoln moves quickly past the idea that the ceremony of which he was part could do anything to commemorate, consecrate, or hallow the ground on which they stood—that had already been done by those who had fought there and sacrificed their lives. Rather, he said, they were there to rededicate themselves and the nation to the “great task remaining.” And what was that great task? Was it victory? Yes, it was certainly that. Was it restoration of the Union? Of course, it was that as well. But, it was also something far more, and it was something that would be, in Lincoln’s mind, the product of both—It was a “new birth of freedom.”

For Lincoln, that was the true goal—the creation of a nation free from the tyranny of human slavery, where all were free to reap the fruits of their labor, where all had value simply for who they were as human beings, where all had the opportunity to make a better life for themselves, no matter their race, their religion, or their ethnicity. And, I believe that, while Lincoln spoke in the sense of the more near term, he knew in his heart that a long road was ahead to truly achieve that kind of freedom in any complete sense. But first, to bring about the birth, victory must come and that would hopefully ensure the preservation of government by, of, and for the people.

So, in that sense, I believe that the true majesty of Lincoln’s words come from seeing them as a challenge to us all, to the generations that would follow, to continue the struggle, to not let those who died at Gettysburg, or hundreds of other places in the all other wars that followed, to have died in vain. In that sense, Lincoln, perhaps, said far more than he realized, and I believe the challenge he laid down that November day is as viable today as it was 147 years ago. As the great narrative historian, Bruce Catton, would write, our republic, our nation, “will survive only if it lives up to the promise that was inherent in its genesis. The fulfillment of that promise is in our keeping.” And that is why I cherish The Gettysburg Address so dearly.