Lee’s concept for the campaign and his reasoning for its timing evolved from a series of Confederate successes in the East and his keen understanding of the need to quickly conclude the war before the South’s weaknesses in men and materiel could no longer be overcome. Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia from a severely wounded Joseph Johnson on June 1, 1862, and had pushed George McClellan and the Army of the Potomac away from the gates of Richmond and back down the Virginia Peninsula in the Seven Days Battles. With McClellan cowering on the James River, he then turned his energies toward John Pope and the newly formed Union Army of Virginia. He outmaneuvered Pope, baffled him completely, and then smashed his new army at Second Manassas. Driving Pope back into the defenses of Washington, by September 1, he found himself poised only 20 miles outside the Federal capital, but poised for what?

He had utterly demoralized both the Union armies of Pope and McClellan. The command situation in Washington was confused. McClellan and the Army of the Potomac had returned up Chesapeake from the Peninsula and McClellan had been relived of command. Lincoln was outraged that his patrician commander had not only squandered opportunities on the Peninsula, but also accused his administration of not supporting the army. McClellan had also been purposely tardy in returning to northern Virginia, where Pope badly needed his support. Thus, the time seemed ripe for action, but what action was called for? Lee felt that another major victory was needed, if not to destroy the Army of the Potomac, then certainly to destroy the will of the Northern people to continue to fight and end the war before the Confederacy’s disadvantages in manpower and resources were exposed.

This was especially true for political reasons that Lee also understood well. November would bring a new round of congressional elections in the North and another crushing defeat might spur the election of more anti-war Democrats to the Congress, who could press the Lincoln administration to pursue a peaceful end to the conflict. Additionally, President Davis was anxious to gain recognition and possibly direct military support from France and, especially, Great Britain. Yet another victory might bring that recognition one step closer to reality. Still, Lee was uncertain which way to move his army.

At the same time, Lee could see that his army was tired from a summer of fighting and badly in need of resupply, which northern Virginia, already stripped clean by Union forces, could not provide. He could retire south and take up positions on the far side of the Rappahannock River, which would allow him to rest, resupply, and reorganize his men. However, this would allow Union forces time to reorganize themselves and also might be seen by the enemy as admitting Lee and his army were incapable of sustained operations in the field. Worst of all, perhaps, it would mean surrendering the initiative Lee had fought so hard to retain all summer long. While Lee knew his army of 75,000 men was tired, he also knew that their morale was high and that they were flush with victory. Meanwhile, his opponents hid behind the Washington fortifications, demoralized from defeat and an uncertain command picture.

Lee knew he had to act and to do so with some speed, lest the advantage he now possessed slip from his fingers. He quickly examined his options and decided that a move into Maryland offered the best chance of success. He seems to have seen this as a grand “turning movement” and one whose primary effects would be political and psychological. For the first time, Confederate forces would cross into Northern soil, threatening not only Washington, but also Harrisburg, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. This would spread panic in the North and almost certainly demand that the Army of the Potomac move out from the fortifications around Washington, attempt to expel the invader from Maryland, and, most importantly, do so before it was prepared to fight.

Further, Lee could resupply his army off the ripe fields of Maryland, and, by drawing Union forces north, allow northern Virginia to recover. At the same time, Lee’s army could interrupt the movement of Union supplies along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal as well as the vital Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Further, Lee could retain the initiative, keep the enemy off balance, and force them to fight at a time and place of Lee’s choosing. Plus, a victory that occurred on Northern soil would not only be seen as further demonstrating the North’s impotence on the battlefield, but their inability to defend home ground might severely damage Union morale to the point that the war effort against the South could not be sustained.

Therefore, on the evening of September 2, only three days after his victory at Second Manassas, Lee issued orders to begin shifting the Army of Northern Virginia into Loudon County in preparation for a crossing of the Potomac River into Maryland. The next morning, he advised President Davis of his plans and the logic behind them via a dispatch, but, interestingly, he did not request permission or wait to receive any. On the morning of September 5, Stonewall Jackson’s corps splashed across the Potomac at White’s Ford north of Leesburg, Virginia, and the campaign into Maryland began.

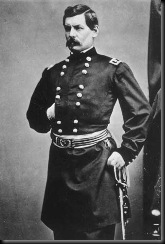

As his army pressed northward, Lee was also relying upon Union forces to supply a commander who would move out quickly from Washington and oblige him by providing openings for a campaign of maneuver. Lee assumed this commander would be John Pope. He had already seen Pope’s inability to properly manage a large army firsthand and he was justifiably confident he could maneuver Pope into a position where he could be destroyed. However, this assumption demonstrates the first of a series of flaws in the intelligence Lee was receiving. Pope was in disgrace and George McClellan’s return to command was already being openly discussed in Washington. While Lee would have felt confidant fighting either Union general, it is interesting that he was unaware of these events and would continue to be so for several critical days. More compelling, however, is the fact that Lee’s plans were contingent on the preconceived behavior of the enemy. Any change in that behavior would be crucial to the success of the campaign and, therefore, any intelligence that indicated a change would be equally vital. As events would prove, that vital intelligence information on the Army of the Potomac would be found severely lacking.

Of all the events during the campaign, this meeting with Stuart was, in my opinion, the most critical, more important even than the lost copy of Special Orders (S.O.), No. 191, which we will examine later. The reason is that Stuart so utterly failed in accomplishing the third and most important part of his assignment. As a result, throughout the coming days, Lee would make decisions based upon intelligence from Stuart that was either incomplete or grossly inaccurate. Stuart was an able cavalryman so long, it seems, as the assignment fed his voracious ego. He was doing all he could to live up to the image of the dashing, daring cavalier and more pedestrian activities, such as collecting intelligence, apparently bored him. Instead, Stuart would indulge himself and his staff with lavish parties at the homes of Southern sympathizers while the Union army steadily approached. Little effort was made to conduct reconnaissance and the reports his men did produce were utterly inadequate.

What is perhaps most surprising about this failure, which nearly cost Lee his army, was that Stuart would be allowed to fail again the next summer during the Gettysburg campaign. Given wide latitude by Lee, he would abandon the army and, instead of monitoring the approaching Army of the Potomac, make a ride around Washington, collecting numerous headlines along the way. The result was that, deep in enemy territory, Lee had no eyes and ears, and he eventually wandered blindly into the Union army at Gettysburg. Had he honestly evaluated Stuart’s performance in Maryland, and confronted him with its results, perhaps Stuart would not have repeated the offense. But, Lee was loath to confront anyone and he hated any disharmony with his staff. He may have realized that Stuart failed him in Maryland, but, if he did so, he made no mention of it, and he certainly did not learn from the experience.

On September 7 and 8, Lee waited in Frederick for news of the garrison at Harper’s Ferry and any Federal advance from Washington. He remained confident that the former must have been evacuated by now and merely needed confirmation of that fact. In a dispatch to Jefferson Davis, he commented that, apparently, the enemy was still not advancing towards him. In actuality, McClellan already had advanced some 60,000 men 12 miles north of Washington in an arc designed to cover any Confederate move towards either the capital or Baltimore, and more troops were following. However, the next day, Lee would learn that Federal troops were on the move. But, for some reason, based on Stuart’s reports, he assumed that the 12 miles they had covered had been traveled since learning of Lee’s movements on September 4. In actuality, they had covered that distance in a single day, and were still steadily advancing. Further, from his dispatches, it is clear that he did not have a clear picture of the organization of the army that was advancing nor was he aware that George McClellan was again in command. As a result, Lee remained quietly confident that he and his army were in no immediate danger.

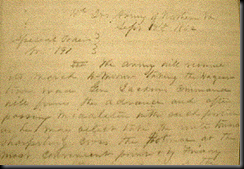

But, September 9 did bring news that the Union garrison at Harper’s Ferry remained stubbornly in-place. Lee had been contemplating a move west towards Hagerstown, hoping that would be enough to stir the enemy to abandon the town, but now he became convinced that something more direct and more drastic was required. In a Council of War held late that afternoon, Lee announced that he was going to divide the army and send Stonewall Jackson at the head of a column to force the Federals out of Harper’s Ferry. His hope was that the mere news of Jackson’s approach would be enough to cause an evacuation, or that, at the least, the arrival of such overwhelming force would create an instantaneous capitulation. At worst, the entire operation should only take a few days, after which Jackson would rejoin the remainder of the army west of the Catoctin Mountains. Given the perceived slow and cautious advance of the Army of the Potomac, there should have been plenty of time. In fact, given Lee’s calculations of the Federal rate of advance, he should be able to complete the entire Maryland Campaign before Union forces even reached Frederick.

Both Longstreet and Jackson opposed Lee’s plan. Dividing the army while deep inside enemy territory was risking disaster in their minds, and it violated every common sense rule of operations. Further, the success of the plan required that Harper’s Ferry be dealt with quickly and easily and that the Army of the Potomac continue to advance at a snail’s pace. Both assumptions would soon prove to be totally incorrect.

On September 10, Lee’s divided army began to move, with Jackson and McLaws heading towards Harper’s Ferry, while Lee and the main body moved west over South Mountain to Boonsboro. Once there, Lee ordered Longstreet to continue west to Hagerstown. On the 11th, Lee heard from Stuart that the cavalry would be forced to retire from Frederick the next day. Lee seems to have assumed that this was because of the arrival of Union cavalry, but, in fact, the forces Stuart observed advancing were actually a division of the Union IX Corps. On the 12th, those Union troops would occupy Frederick and Lee would learn that the Harper’s Ferry garrison was stubbornly refusing to leave. His timetable was not proceeding as planned, which upset him, but not nearly as much as the news he received the next day informing him that Frederick had not merely been occupied by cavalry, but, rather, the town was now host to a large force of Union infantry.

Still, Lee did not panic and was not overly concerned by this turn of events. He was worried that the slowness of the effort to secure Harper’s Ferry might endanger Jackson’s force if it took much longer to complete, but, due to continuing faulty intelligence from Stuart, he had yet to realize the size and proximity of the Army of the Potomac. However, by the time the evening of September 13 was over, Lee would find his entire plan seemed to be collapsing about him. First, he was informed that Union infantry were not just in Frederick but that they had moved west and were already approaching the passes over South Mountain. Prior to this time, Lee had not planned to defend the passes and intended to allow the Union army to come forward unmolested. However, he never anticipated them being so perilously close while his army was divided. Now, he would be forced to defend the passes and try to slow their advance. But, no sooner had he dispatched units to defend the passes than he learned that George McClellan had a copy of S.O. No. 191, which had apparently been carelessly dropped only to be found by a Union soldier after the occupation of Frederick. McClellan now knew that Lee had divided the army and was at that very moment pushing his entire army to the passes over South Mountain in an attempt to catch Lee before he could reunite the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee now must have fully realized that he had lost the initiative. He realized the campaign and his entire army was in danger. Still, he did not panic and he seems to have been determined to find a way to regain the initiative and salvage the campaign—too much was riding on its success to do otherwise. Lee’s analysis told him that McClellan would most likely move to relief Harper’s Ferry, which was in error. His plan was to mount a vigorous defense of the passes over South Mountain and hold McClellan at bay until Harper’s Ferry had surrendered. Then, he would reunite his army at Sharpsburg on the northern banks of the Potomac and proceed onward to Hagerstown, still free to maneuver until he could get the Army of the Potomac where he wanted them.

Early the next morning, Lee arrived in Sharpsburg in preparation to move across the Potomac. However, as Lee was enjoying a cup of coffee, a dispatch rider arrived from Harper’s Ferry with a message from Jackson. The message told Lee that his corps commander expected the Union garrison to fall later that day. Suddenly, Lee saw a new opportunity. If he could make a defensive stand at Sharpsburg until Jackson and McLaws could join him, he might then extract himself, move toward Hagerstown, and regain the initiative. He issued orders to both men to join him in Sharpsburg as quickly as they had completed the operation at Harper’s Ferry and set about standing up defensive positions on the hills outside of town.

With his back to the river, Lee did not have the best of positions, and he did not have enough resources to close his flanks against the banks of the river. Further, in a more general sense, Lee’s decision to regain the initiative ignored an important reality: the condition of his army. His men had been marching almost constantly since September 4, and the losses experienced defending South Mountain were greater than he probably realized. Fatigue and casualties had taken a toll. But Lee refused to see that. He had apparently begun to develop a sense, even a dangerous belief, that his army could do anything he asked of it.

On September 16, Lee hoped that Jackson would join him soon enough to allow the army to move west before it was confronted by the bulk of McClellan’s army. However, by the time Jackson arrived and took up positions on Lee’s defensive line, the Army of the Potomac arrived in full force. Lee would now be forced to give battle, and his last real chance to maneuver, to regain the initiative, was lost.

Later in the day, Lee experienced two near-disasters and two strokes of luck. With his center weakened, just as McClellan desired, Federal forces overran Confederate units at the Sunken Road, exposing Lee’s entire center. But, rather than commit his reserves to break Lee in two, the always timid McClellan held back. And, in late afternoon, when Burnside’s corps had forced the lower bridge over Antietam Creek and was rolling up Lee’s right flank, the last of Jackson’s corps under A.P. Hill would arrive on the field and blunt the Union attack. As with any great general, Lee was saved by a generous portion of luck in the form of an overly cautious opponent who became so at just the right moment and good timing by A.P. Hill.

The next day, both armies remained in place, cautiously eyeing one another. For his part, Lee was trying to find a way to break out and continue to maneuver in the direction of Hagerstown. He presented several plans, but his staff convinced him that none were viable given the condition of the army. Finally, he ordered the army to move across the Potomac that night. Many analysts have seen this simply as Lee’s decision to retreat back to Virginia and end the Maryland Campaign. However, that is not the case or, at least, it was not so in Lee’s mind when he issued the order. Lee planned to simply change his base by moving to the south bank of the river, and then go upriver to Williamsport, where he would re-cross the Potomac and, once again, enter Maryland with the initiative restored. At this point, Lee’s desire to continue the campaign was bordering on an obsession.

Lee would actually send cavalry towards Williamsport to ensure the ford was not defended, with infantry close behind. But before he could shift the army, his senior commanders prevailed upon him and convinced him that his army was too tired, too demoralized, and too beat up to continue the campaign. On September 21, he would begin moving the army back to the banks of the Rappahannock for rest and resupply. The Maryland Campaign was at an end.

Robert E. Lee’s reasons for executing the Maryland Campaign demonstrated a sound and keen understanding of the strategic situation facing the Confederacy and his initial plan was audacious and bold, but not to the point of being overly fraught with risk. However, he made the mistake of assuming that his enemy would keep to playing their role in the “script” as Lee had written it. Despite it being against all traditional military thinking, the Union commander at Harper’s Ferry would not leave, forcing Lee to take the risk of dividing his army. Worst of all, however, was the speed at which George McClellan restored the morale of his army and moved forward to confront Lee. Here, Lee was plagued by bad intelligence and the failures of Jeb Stuart. However, Lee was guilty of accepting this intelligence at face value simply because it fit the plan he had so carefully crafted. As a result, he had lost the precious initiative he valued so highly long before anyone placed a copy of S.O. No. 191 in McClellan’s hands. However, perhaps worst of all, Lee would learn little from his experience in Maryland and he would move into Pennsylvania during the summer of 1863 with a reliance on Jeb Stuart and an unshakable belief that, once again, the Army of the Potomac would remain demoralized, as was its part in his script.

Brava! Articulately written, informative and well worth the wait!!

ReplyDeleteGreat summary of Lee's Maryland Campaign. I agree that Stuart's efforts at discerning the movements of the Union army was feeble. I am curious about your belief that Lee was counting on swift movement of Union forces out of the DC defenses to chase him into western Maryland. Everything I've seen indicate that he was counting on the slow movement of Union forces so that the Rebel army could rest and feast on the Maryland countryside and then move into Pennsylvania doing so there also while gradually drawing the Yankees further from DC and its line of communications. I would appreciate any references you have showing that Lee wanted swift movement from his foes.

ReplyDeleteThank you,

Larry Freiheit

Larry,

ReplyDeleteI tend to agree with historian Joseph L. Harsh's analysis of Lee's intitial campaign planning. In "Taken at the Flood," Harsh cites several sources that indicate Lee's initial thinking was to get a disorganized, demoralized Union army into a fight as soon as possible. But all that was based upon a secure line of communication through the Shenandoah. Therefore, when the Harper's Ferry garrison did not abdandon their position, Lee was glad the Federal response was slower than originally hoped for.

Bob

I'm with you Bob, on the issue of Joseph L. Harsh's analysis of Lee's campaign planning at the beginning of precedings. I also think that Lee would bought himself a bunch of lottery tickets if such things existed in those days (which of course they didn't) given his extraordinary luck with the slackness of the federal response.

ReplyDeleteNorman Potter

seashells for crafts