In the late summer and early fall of 1864, a new Union army, the Army of the Shenandoah, would pursue a campaign designed to drive Confederate forces from Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, once and for all. General Ulysses S. Grant’s purpose in ordering the campaign was to deny the valley as both an avenue of attack and a source of sustenance for the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. While the numbers of troops involved on both sides was relatively small compared to the other campaigns of 1864, the outcome would prove significant to the course of the war. At the time it occurred, the campaign was celebrated in the North and its success was, along with Sherman’s capture of Atlanta, a key ingredient in President Lincoln’s re-election.

In fact, it could be argued that, in the last years of the 19th century, the campaign’s final dramatic battle was as famous to many Americans as Gettysburg or Shiloh. That same battle even inspired a poem which was memorized at one time or another by almost every schoolboy north of the Mason-Dixon Line. For the South, meanwhile, the campaign not only ended a bold gamble by Robert E. Lee that had taken Confederate forces to the gates of Washington D.C., it also resulted in the brutal destruction of hundreds of valley farms. In doing so, it drove one more critical nail into the coffin of the Confederacy.

However, as time passed, the campaign lost its historical notoriety, which probably explains why so much of the three key battlegrounds of the campaign have been either threatened by or lost to commercial development. Only in the last 15 years has a concerted effort been mounted to save these fields and, through the work of organizations such as the Civil War Preservation Trust, some has been saved. So, let’s examine this campaign and its three major battles.

However, Union efforts to maintain any hold on the valley had been constantly frustrated. While Union forces would occupy Harper’s Ferry for much of the war, they had never been able to successfully prosecute any campaign to take the remainder of the valley. In 1862, Stonewall Jackson had run rings around three different Federal armies, embarrassing them in a series of stunning defeats. After that, Lee had been able to secure the valley during his campaign into Maryland in September 1862, and use it as a route of invasion when he moved into Pennsylvania during the summer of 1863. Then, as Lee savagely struggled with Grant and Meade during the summer of 1864, he again decided to make use of the valley in a bold gamble designed to relieve Grant’s stranglehold on him at Petersburg.

Early’s forces were primarily remnants of Stonewall Jackson’s famous “foot cavalry,” the once magnificent infantry that had raced up and down the valley in 1862, confounding and smashing all the Union armies sent after them. First, there was Breckenridge’s Corps, led by General John C. Breckenridge, a former Vice President of the United States and an able soldier. Breckenridge’s divisions were led by a talented group of field officers including the steady and reliable Robert Rodes, dashing young Stephen Ramseur, and the tough, charismatic Georgian, John B. Gordon.

Despite his shortcomings, Early’s campaign was initially something of a success. He was able to slip away from Petersburg unnoticed and proceeded to drive Hunter’s army back into West Virginia. From there, his army marched down the valley to the Potomac, crossed into Maryland, and turned towards Washington. While this was happening, Grant was unable to get reliable intelligence on the size or composition of the Confederate force operating in the valley, and, as a result, did not seem to be overly concerned. However, once this new Southern army seemed poised to take Washington, the pressure to act was too great. Grant had, after all, stripped the defenses of Washington of all but the lowliest of troops to support his campaign against Lee. Now, there was virtually no one left to man the fortifications surrounding the city and, if Early wanted to take the capital, it was essentially there for the taking. On July 6, Grant pulled two brigades of the Third Division of the veteran VI Corps out of the lines at Petersburg and sent them to board ships bound for Baltimore. He hoped that these 5,000 men would be enough.

As the two VI Corps brigades raced northward, Early and his army was approaching Frederick, Maryland. Union General Lew Wallace, who would later gain fame as the author of Ben Hur, mobilized a motley, ragtag force of militia, cavalry, and light artillery and headed west to Monocacy Junction, just across the Monocacy River from Frederick, to meet Early. He had little hope of even holding the

Early would pause, then move forward to the outskirts of Washington, arriving on July 11. His army was now approaching exhaustion and, as he peered through his glasses at the capitol dome, the always aggressive Early hesitated. He waited one day to attack, but, when the moment came, Early discovered that the fortifications that had been almost empty the day before were now manned in force by the remainder of the VI Corps, which Grant had dispatched while Early was engaged with Wallace at Monocacy. The opportunity to take the Federal capital

With Early’s near success, Grant decided that the Shenandoah Valley must be dealt with and eliminated as both an avenue of attack and a source of supply for Lee. He traveled to Washington to confer with the president and Secretary of War Stanton. Grant proposed unifying several military departments into one, creating a new Army of the Shenandoah, and tasking its commander to drive Early out of the valley, destroying his army if at all possible, and wreaking havoc on the farms and fields that were feeding Lee’s army. There was a debate as to who should lead this new army, and even George McClellan’s name was mentioned in the discussions. Finally, over the objection of some, Grant named General Philip Sheridan to the new post. Initially, Sheridan was to serve merely as a field commander under the direction of General Hunter, who was the department commander. However, Hunter quickly resigned and Sheridan assumed complete command.

Grant’s orders to Sheridan were simple and clear:

In pushing up the Shenandoah Valley, as it is expected you will have to go, first or last, it is desirable that nothing should be left to invite the enemy to return. Take all provisions, forage, and stock wanted for the use of your command; such as cannot be consumed, destroy. It is not desirable that the buildings should be destroyed; they should rather be protected; but the people should be informed that so long as an army can subsist among them recurrences of these raids must be expected, and we are determined to stop them at all hazards. Bear in mind the object is to drive the enemy south, and to do this you want to keep him always in sight. Be guided in your course by the course he takes.

Sheridan immediately put the army in motion and pointed them south, up the valley. On August 10, the army moved towards Bulltown and Sheridan hoped this would get Early’s attention and cause him to fall back toward Winchester. Early did exactly as Sheridan had hoped but the Union general received some disquieting news that caused him to slow his advance. Lee had heard of the formation of Sheridan’s army and knew that Early must be its target. Therefore, he began shifting a division of infantry under General Kershaw, some artillery, and Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry to Early. Grant received intelligence of this fact and sent a dispatch to General Halleck urging caution.

Inform Sheridan that it is now certain two divisions of infantry have gone to Early and some cavalry and twenty pieces of artillery. This movement commenced last Saturday night. He must be cautious and act now on the defensive until movements here force them to detach to send this way. Early's force, with this increase, cannot exceed 40,000, but this is too much for Sheridan to attack.

Sheridan continued a slow movement towards Early, but when news of the Confederate reinforcements was confirmed, he withdrew back to Halltown on August 23. This, in turn, led Early to believe that he was facing a timid opponent and, once his reinforcements did arrive, he began to behave more aggressively, moving some of his force to Charlestown and, at one point, even making a feint that was designed to make Sheridan believe he might move into Maryland. Early soon returned to Bunker Hill, but kept up cavalry patrols along Opequon Creek, which resulted in numerous skirmishes. One Union officer described this pattern between Sheridan and Early as “Mimic War” and it continued into early September.

Grant soon grew tired of this lack of offensive action and feared that his orders to that effect were not getting to Sheridan. Therefore, Grant proposed a meeting with Sheridan for September 15, at which he planned to provide him with an operational plan of Grant’s own making. Grant later described the meeting in his memoirs:

On the 15th of September I started to visit General Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley. My purpose was to have him attack Early, or drive him out of the valley and destroy that source of supplies for Lee's army. I knew it was impossible for me to get orders through Washington to Sheridan to make a move, because they would be stopped there and such orders as Halleck's caution (and that of the Secretary of War) would suggest would be given instead, and would, no doubt, be contradictory to mine. I therefore, without stopping at Washington, went directly through to Charlestown, some ten miles above Harper's Ferry, and waited there to see General Sheridan, having sent a courier in advance to inform him where to meet me.

When Sheridan arrived I asked him if he had a map showing the positions of his army and that of the enemy. He at once drew one out of his side pocket, showing all roads and streams, and the camps of the two armies. He said that if he had permission he would move so and so (pointing out how) against the Confederates, and that he could "whip them." Before starting I had drawn up a plan of campaign for Sheridan, which I had brought with me; but, seeing that he was so clear and so positive in his views and so confident of success, I said nothing about this and did not take it out of my pocket.

At 1:00 a.m. on the morning of September 19, Sheridan began his campaign against Early in earnest, ordering his army to advance towards Winchester on the Winchester-Berryville Pike. Wilson’s cavalry division led the way, crossing Opequon Creek, then moving through a narrow defile known as Berryville Canyon, followed by the XIX and VI Corps. Sheridan’s plan was for the cavalry to sweep away any Confederate pickets in the canyon, then seize the open ground beyond, allowing the infantry of VI and XIX Corps to quickly form up and attack. However, his plan was far too optimistic about the speed at which the infantry would move through the canyon and could have been a fatal error. The cavalry swiftly made it through the narrow passage, scattered the pickets at the far end, and moved forward to the attack, charging the elements of Ramseur’s Division that were blocking the pike ahead.

However, as the Federal troopers crashed unsuccessfully against Ramseur’s line, the infantry got hopelessly bogged down in the canyon amid a jam of men and wagons. As a result, the initiative was lost and Early had time to react, moving more men into position on Ramseur’s left. Had Sheridan’s plan worked, Early would have been the one in trouble. Convinced that he was facing a slow, cautious opponent, he had placed his men in position carelessly, with huge gaps between each division’s flank. Now, however, he was quickly trying to close those gaps to meet Sheridan’s assault, which would not get underway until almost noon.

As the VI and XIX Corps were struggling against Early’s infantry, Sheridan’s cavalry went into action. Early’s misuse of his cavalry during the campaign would stand in stark contrast to Sheridan’s brilliant employment of his mounted forces. Throughout the campaign, Sheridan would use his cavalry effectively in concert with his infantry in a true “combined arms” approach. On this morning, that began with Merritt’s cavalry division pushing down from north of Winchester, forcing Confederate cavalry backward.

After Upton’s counterattack stopped the Confederate advance, Sheridan ordered Crook to bring his West Virginians and Ohioans forward from their reserve position in the rear.

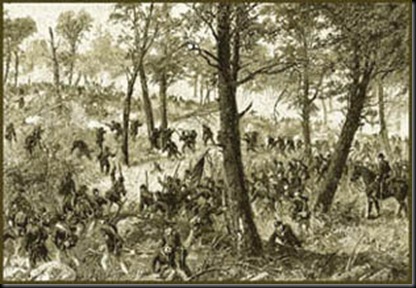

With the success of Crook’s attack and the realignment of Early’s forces, Sheridan saw an opportunity to break the Confederate defenses. He ordered a massive general advance of the entire army against the Southern position just north and east of Winchester. As the long blue line surged forward, the din of battle became incredible, with a constant crash of artillery and rifle fire. The Confederates held desperately onto their positions because they essentially had nowhere to go. Behind them lay the streets and houses of Winchester where there would be no chance to set up a defense. If they fell back, it would have to be in full retreat.

As night fell, Early withdrew his army up the Valley Pike to Fisher's Hill south of Strasburg. Sheridan’s men were too disorganized by their victory to immediately pursue and they halted in Winchester. Casualties were heavy on both sides, with Union killed, wounded, and missing totaling over 5,000 men, while Early lost more than 3,000 men he could ill afford to lose. The first round of the fight for the Shenandoah was over, and Sheridan was the clear victor.

Can you tell us where the Hazelwood House is located?

ReplyDeleteActually, that's a typo, which I have now corrected. It was Hackwood House and if you go to the Civil War Preservation Trust web site and access the walking tour map of the battlefield, you will see it. There is a wayside sign on the tour opposite the house where Crook's men deployed for their attack.

ReplyDeleteMy Great Grandfather was a Confederate private in "F" Company, 26th Virginia Infranty Battalion. He was captured in Third Battle of Winchester on Sept. 19, 1864. He later died while a prisoner at Point Lookout, Maryland. His oldest son, my great uncle, was on the same field of battle and saw his father taken captive. He later told family members that their position was attack by Union Calvary with sabers. My Great Grandfather and his son were from Monroe County, West Virginia. My question to you is, do you know where the 26th Virginia was located on the field of battle? I hope to see your response posted here. Thank you. Bernard

ReplyDeleteBernard:

ReplyDeleteAs best I can tell, the 26th Virginia was probably with Wharton on the far left of Early's line. That would mean they bore the brunt of Averell and Merritt's initial cavalry attacks, hence your Great Grandfather's recollection of being attacked by Federal cavalry. I will have access to some more source material this weekend and will update this if I find anything new.

Bob

Q. My 2nd Great-Grandfather was with Company "A" of the 22nd Virginia Infranty and was capatured on Sept. 19, 1864 - I have found some of his records with the 22nd and his Point Lookout POW records - my question is do you know where the 22nd was on the morning of the 19th, 1864 and where Company "A" was at the time of the battle. I am planning a trip to Winchester the week of April 22nd, 2013 and any information would be appreciated - tmdavis1017@comcast.net

ReplyDelete