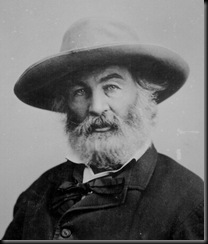

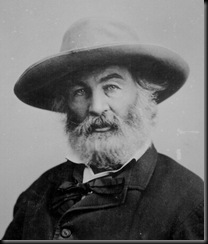

Walt Whitman is known to many of us as one of the truly great American poets, and a man whose stature as such is probably only equaled by poets such as Robert Frost. However, at the same time, most Americans know little of Whitman’s Civil War experiences. In the months and years immediately preceding the war, Whitman’s once promising career was going nowhere. But, the war and Whitman’s experience working in the military hospitals around Washington would change that. In many ways, the Civil War “saved” Walt Whitman, and, just as the war saved the nation, it also saved a man who would become known to many wounded and ill veterans as the “Good Gray Poet.” This was a critical chapter in Whitman’s life but is one that has never received much attention despite the large number of biographies of the poet. During this period of his life, Walt Whitman was the living example of what Lincoln meant when he referred to “the better angels of our nature.”

Walt Whitman is known to many of us as one of the truly great American poets, and a man whose stature as such is probably only equaled by poets such as Robert Frost. However, at the same time, most Americans know little of Whitman’s Civil War experiences. In the months and years immediately preceding the war, Whitman’s once promising career was going nowhere. But, the war and Whitman’s experience working in the military hospitals around Washington would change that. In many ways, the Civil War “saved” Walt Whitman, and, just as the war saved the nation, it also saved a man who would become known to many wounded and ill veterans as the “Good Gray Poet.” This was a critical chapter in Whitman’s life but is one that has never received much attention despite the large number of biographies of the poet. During this period of his life, Walt Whitman was the living example of what Lincoln meant when he referred to “the better angels of our nature.”

In 1855, with the publication of Leaves of Grass, Whitman seemed poised to become the great poet of his generation. However, by 1861, both his personal and professional life had become complete disasters. Whitman, who was gay, seemed to hit bottom, living a life that can best be described as utterly bohemian, filled with late-night carousing, and homosexual cruising. But, the onset of the war would energize Whitman who passionately believed in the cause of the Union. Initially, he searched in vain for a way to support that cause but, eventually, he found an outlet for his passion tending to what he himself referred to as “The Great Army of the Sick.” Whitman became totally dedicated to his task, visiting the hospitals each and every day. What Whitman saw horrified him. But, it also inspired him.

In 1855, with the publication of Leaves of Grass, Whitman seemed poised to become the great poet of his generation. However, by 1861, both his personal and professional life had become complete disasters. Whitman, who was gay, seemed to hit bottom, living a life that can best be described as utterly bohemian, filled with late-night carousing, and homosexual cruising. But, the onset of the war would energize Whitman who passionately believed in the cause of the Union. Initially, he searched in vain for a way to support that cause but, eventually, he found an outlet for his passion tending to what he himself referred to as “The Great Army of the Sick.” Whitman became totally dedicated to his task, visiting the hospitals each and every day. What Whitman saw horrified him. But, it also inspired him.

On the one hand, he saw a dedicated medical community trying desperately to provide care to a staggering number of sick and wounded, using drugs and standards of care which would seem as nothing less than bizarre to a modern observer. Even when viewed in the context of the medical knowledge of the times, the results and consequences of the prescribed treatments seem like the products of a nightmare. The shear damage to muscle and bone that Whitman witnessed did certainly horrify him, but it was the absence of any treatment for the heart and the soul that truly brought him to despair. And that is where Walt Whitman decided that he might serve.

On the one hand, he saw a dedicated medical community trying desperately to provide care to a staggering number of sick and wounded, using drugs and standards of care which would seem as nothing less than bizarre to a modern observer. Even when viewed in the context of the medical knowledge of the times, the results and consequences of the prescribed treatments seem like the products of a nightmare. The shear damage to muscle and bone that Whitman witnessed did certainly horrify him, but it was the absence of any treatment for the heart and the soul that truly brought him to despair. And that is where Walt Whitman decided that he might serve.

Whitman found that male orderlies, who he viewed as a generally ill-tempered lot, and even female nurses, treated the wounded coldly with complete formality, and never with even a kind word. In fact, most had been trained to behave in exactly this manner. One nurse recalled that she was instructed to “put away all feelings. Do all you can and be a machine—that’s the way to act; the only way.” The hospitals did, however, allow and even encourage visits by various religious organizations. But, unfortunately, these visitors often lectured and shouted to wounded, suffering soldiers about their sins and how they must repent. There was seldom a mention of mercy or of God’s love.

In response, Whitman employed an approach that was remarkably simple: he was kind. Walt Whitman provided an invaluable service to thousands of wounded and sick soldiers merely by being their friend. He would bring small gifts, sit by their beds and listen to them speak of their homes, their hopes, and their fears. He would also write letters for those who were unable to do so, lend a gentle hand to hold, and even provide that last, tender moment of human contact that so many of the dying needed. At times, he would clash with the more official parts of the medical system, particularly those who had turned off their emotions and showed no sign of kindness, as well as those intent on preaching endlessly about sin to men who wanted nothing more than a kind and comforting voice. A colonel from Kansas remembered his experience with Whitman as contrasted with other visitors:

In response, Whitman employed an approach that was remarkably simple: he was kind. Walt Whitman provided an invaluable service to thousands of wounded and sick soldiers merely by being their friend. He would bring small gifts, sit by their beds and listen to them speak of their homes, their hopes, and their fears. He would also write letters for those who were unable to do so, lend a gentle hand to hold, and even provide that last, tender moment of human contact that so many of the dying needed. At times, he would clash with the more official parts of the medical system, particularly those who had turned off their emotions and showed no sign of kindness, as well as those intent on preaching endlessly about sin to men who wanted nothing more than a kind and comforting voice. A colonel from Kansas remembered his experience with Whitman as contrasted with other visitors:

When this old heathen came and gave me a pipe and tobacco, it was about the most joyous moment of my life….I don’t mean to say he was the only one who visited the hospital. There were plenty of others I assure you. The little bay at the head of my cot was full of tracts and testaments, and every Sunday there were half a dozen old roosters who would come into my ward and preach and pray and sing to us, while we were swearing to ourselves all the time, and wishing the blamed fools would go away. Walt Whitman’s funny stories, and his pipes and tobacco were worth more than all the preachers and tracts in Christendom. A wounded soldier don’t like to be reminded of his God more than twenty times a day. Walt Whitman didn’t bring any tracts or Bibles; he didn’t ask if you loved the Lord, and didn’t seem to care whether you did or not.

And, to be sure, the pain and death Whitman saw took its toll on him. After witnessing the death on the operating table of one soldier who had bravely and patiently waited until he was strong enough for surgery, Whitman wrote his mother:

Mother, such things are awful—not a soul here he knew or cared about except me…how contemptible all the usual little worldly prides & vanities & striving after appearances seem in the midst of such scenes as these…To see such things & not be able to help them is awful—I feel almost ashamed of being so well and whole.

At times, Whitman became understandably embittered, once telling a friend, “The people who like the wars should be compelled to fight the wars.”

At times, Whitman became understandably embittered, once telling a friend, “The people who like the wars should be compelled to fight the wars.”

But, as I said earlier, Whitman was also inspired by what he saw in the hospitals, by what he saw in these men and young boys. Whitman perceived a deep nobility in their quiet bravery, their continued dedication to their country and cause, no matter the pains they now suffered. To him, they came to symbolize all that was good in his country, and it was this bravery, this nobility, that saved him, that eventually turned his life around. As author Roy Morris wrote, “The fire that he nursed within his heart for the gallant young men in the great army of the sick would prove to be, in the face of harsher trials to come, a steadfast and abiding flame.”

Whitman would write hundreds of letters for soldiers to their wives, sweethearts, and parents during the course of the war. However, among all those letters, one truly stands out for me as embodying Walt Whitman’s humanity and his love for the soldiers he served so well. This remarkable letter was written to the parents of a young soldier, nineteen-year old Private Erastus Haskell of the 141st New York Infantry Regiment. Eratus had fallen ill with typhoid and was shipped to the Armory Square Hospital in Washington for treatment. Whitman visited him almost daily during the soldier’s last weeks and described him as a shy, sensible boy with “fine manners” who never complained. While the doctors fought to save him with all their seemingly primitive tools, Erastus eventually succumbed to the disease. Whitman wrote a letter to the boy’s parents, telling them about their son’s last days, the contents of which are simple, heartfelt, and incredibly moving. Using his remarkable literary talents, Whitman describes this young soldier’s quiet nobility, and even the dimly lit silence of the hospital ward on the night of his death, in beautiful prose. Whitman concludes his letter by saying that,

Whitman would write hundreds of letters for soldiers to their wives, sweethearts, and parents during the course of the war. However, among all those letters, one truly stands out for me as embodying Walt Whitman’s humanity and his love for the soldiers he served so well. This remarkable letter was written to the parents of a young soldier, nineteen-year old Private Erastus Haskell of the 141st New York Infantry Regiment. Eratus had fallen ill with typhoid and was shipped to the Armory Square Hospital in Washington for treatment. Whitman visited him almost daily during the soldier’s last weeks and described him as a shy, sensible boy with “fine manners” who never complained. While the doctors fought to save him with all their seemingly primitive tools, Erastus eventually succumbed to the disease. Whitman wrote a letter to the boy’s parents, telling them about their son’s last days, the contents of which are simple, heartfelt, and incredibly moving. Using his remarkable literary talents, Whitman describes this young soldier’s quiet nobility, and even the dimly lit silence of the hospital ward on the night of his death, in beautiful prose. Whitman concludes his letter by saying that,

…his fate was a hard one, to die so-He is one of the thousands of our unknown American young men in the ranks about whom there is no record or fame, no fuss made about their dying so unknown, but I find in them the real precious & royal ones of this land giving themselves up, aye even their young & precious lives, in their country's cause…So farewell, dear boy—it was my opportunity to be with you in your last rapid days of death—no chance as I have said to do anything particular, for nothing could be done—only you did not lay here & die among strangers without having one at hand who loved you dearly, & to whom you gave your dying kiss.

In this single letter, one can sense Whitman’s sense of pride, pain, and frustration in very real terms. In the end, all he could do for Erastus Haskell, as with so many of the soldiers he would come to know, was be his friend and assure he did not die among strangers. One wonders if Whitman realized how much he was giving by such a simple act.

There were no medals given to Walt Whitman for his service. Rather, he received something better. Walt Whitman would always carry with him the love and gratitude of the soldiers he admired, respected, and loved so much. So, in addition to his rank among American poets, let us add to his laurels for simply being a kind, compassionate, and generous human being.

There were no medals given to Walt Whitman for his service. Rather, he received something better. Walt Whitman would always carry with him the love and gratitude of the soldiers he admired, respected, and loved so much. So, in addition to his rank among American poets, let us add to his laurels for simply being a kind, compassionate, and generous human being.

What an incredibly wonderful display of the darkness and feelings of being lost with the human soul. In comes Whitman with his own demons and redemption, for him and for those that he touched! The pictures add a great touch of reality.

ReplyDeleteWhat a moving description of Whitman's feeling about the Civil War, and his kindness to and compassion for the wounded soldiers. To see more--and feel more--about this, those in the NYC Metro area should know of a great event to take place on Saturday, April 16, 2011 at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation. It will include a powerful lecture by Eli Siegel "Hot & Cold Tell of Poetry"--on Walt Whitman’s Specimen Days & the Civil War. Here's a link to the announcement: http://www.aestheticrealism.org/events2.htm

ReplyDeleteAs April is National Poetry Month, and this year commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, I want to thank you for this wonderful remembrance of Walt Whitman's selfless service to our soldiers. As a US Army veteran, occasional poet, and Civil War buff, I'm pleased to share this with my Facebook friends.

ReplyDelete