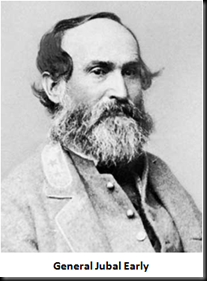

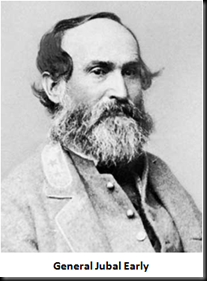

After the debacle at Fisher’s Hill, Jubal Early led his shattered army further south up the Shenandoah Valley, with Philip Sheridan slowly following at a distance. By September 25, three days after the battle at Fisher’s Hill, Early brought his army to a halt in Brown’s Gap of the Blue Ridge. He posted his cavalry near Port Republic, between himself and the Union cavalry that were trailing him. As for Sheridan and the infantry, they broke off their slow pursuit and turned towards Harrisonburg, some 10 miles west of Port Republic.

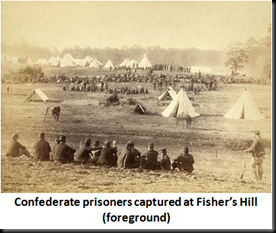

From his bivouac amid the Blue Ridge, Early totaled the results of the twin disasters that befell him and his army at Winchester and Fisher’s Hill. His four divisions of infantry now contained about 7,200 men, and his artillery could only muster 23 guns manned by 850 men. Worst of all, however, had been the loss of leadership in the army, which was so necessary to maintaining good discipline. General Rodes was dead, killed at Winchester, and Fitzhugh Lee had been badly wounded in the same engagement. But, what was perhaps more grievous were the losses among field officers, the men required to command at the tactical level in combat. In Ramseur’s Division, one brigade had not a single surviving officer amongst its five regiments, with the 4th North Carolina being led by a young second lieutenant. The other three brigades were only slightly better with two of them having two field officers each, while the third had three officers to spread across five regiments. Early would officially report to Lee that “my troops are very much shattered, the men very much exhausted, and many of them without shoes.”

From his bivouac amid the Blue Ridge, Early totaled the results of the twin disasters that befell him and his army at Winchester and Fisher’s Hill. His four divisions of infantry now contained about 7,200 men, and his artillery could only muster 23 guns manned by 850 men. Worst of all, however, had been the loss of leadership in the army, which was so necessary to maintaining good discipline. General Rodes was dead, killed at Winchester, and Fitzhugh Lee had been badly wounded in the same engagement. But, what was perhaps more grievous were the losses among field officers, the men required to command at the tactical level in combat. In Ramseur’s Division, one brigade had not a single surviving officer amongst its five regiments, with the 4th North Carolina being led by a young second lieutenant. The other three brigades were only slightly better with two of them having two field officers each, while the third had three officers to spread across five regiments. Early would officially report to Lee that “my troops are very much shattered, the men very much exhausted, and many of them without shoes.”

With the stunning losses in the valley, Lee was pressured both publicly in the press and privately by even the governor of Virginia to remove Early from command. However, Lee had no one else to send and, therefore, “Old Jube” would have to do. But, do what? If Lee brought the Army of the Valley back to Petersburg and Richmond, that would only mean that Sheridan’s entire army could either return to further strengthen Grant or, perhaps worse, he could come through the Blue Ridge and threaten Lee from the rear. No, Lee decided, Early would have to stay in the valley.

However, the question remained as to what Early could hope to accomplish. He was badly outnumbered and told Lee so, providing an accurate picture of the situation. On September 23, he sent a dispatch to Lee in which he told the commanding general that, “The enemy's infantry force was nearly, if not quite, three times as large as mine, and his cavalry was very much superior, both in numbers and equipment.” But, Lee would not accept his general’s assessment of Sheridan’s strength. He wrote back to Early stating, “The enemy's force cannot be so greatly superior to yours. His effective infantry, I do not think, exceeds 12,000 men.” In addition to vastly underestimating Sheridan’s strength, Lee pushed Early to achieve a resounding victory. In Lee’s mind, he had sent Early to the valley to rout Union forces and that is what he would still have to do. Lee badly needed his bold gamble in the valley to succeed and, therefore, success was now required.

However, the question remained as to what Early could hope to accomplish. He was badly outnumbered and told Lee so, providing an accurate picture of the situation. On September 23, he sent a dispatch to Lee in which he told the commanding general that, “The enemy's infantry force was nearly, if not quite, three times as large as mine, and his cavalry was very much superior, both in numbers and equipment.” But, Lee would not accept his general’s assessment of Sheridan’s strength. He wrote back to Early stating, “The enemy's force cannot be so greatly superior to yours. His effective infantry, I do not think, exceeds 12,000 men.” In addition to vastly underestimating Sheridan’s strength, Lee pushed Early to achieve a resounding victory. In Lee’s mind, he had sent Early to the valley to rout Union forces and that is what he would still have to do. Lee badly needed his bold gamble in the valley to succeed and, therefore, success was now required.

To aid in this, Lee sent Kershaw’s Division back to join Early, and they arrived on September 26. In the same dispatch to Early in which he understated Union numbers, Lee went on to direct Early to achieve what must have seemed impossible:

I very much regret the reverses that have occurred to the army in the Valley, but trust they can be remedied. The arrival of Kershaw will add greatly to your strength, and I have such confidence in the men and officers that I am sure all will unite in the defense of the country. It will require that every one should exert all his energies and strength to meet the emergency. One victory will put all things right. You must do all in your power to invigorate your army. Get back all absentees; maneuver so, if you can, as to keep the enemy in check until you can strike him with all your strength…It will require the greatest watchfulness, the greatest promptness, and the most untiring energy on your part to arrest the progress of the enemy in his present tide of success…I have given you all I can; you must use the resources you have so as to gain success. The enemy must be defeated, and I rely upon you to do it. I will endeavor to have shoes, arms, and ammunition supplied you. Set all your officers to work bravely and hopefully, and all will go well…We are obliged to fight against great odds. A kind Providence will yet overrule everything for our good.

So, there it was: depend upon Providence, achieve one great, miraculous victory, and all would be right. What Early truly thought about these words from his commander are unknown to history, but one wonders if he must have thought Lee simply did not understand the situation. However, Jubal Early was nothing if not totally loyal to Robert E. Lee and set about trying to accomplish what he had been asked to do.

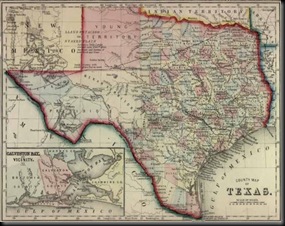

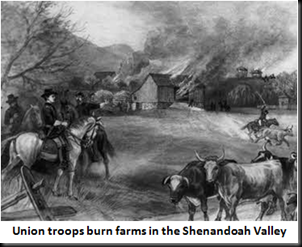

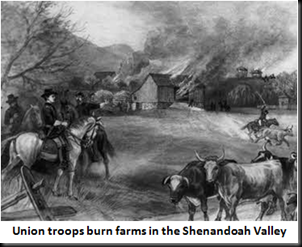

Luckily for Early, his opponent became embroiled in a three-week debate with Grant as to what should be done next. As that debate ensued, Sheridan made no effort to pursue and destroy Early’s army. Rather, thinking Early posed little real threat any more, he began a slow retrograde down the valley.  However, as he did so, he set about performing the other job he had been assigned by Grant at the beginning of the campaign: destroying the Confederacy’s source of supply in the Shenandoah. Sheridan’s army methodically and systematically put the Shenandoah Valley to the torch. Crops, barns, and grain stores were burned, and any livestock that the army did not need for its own subsistence were mercilessly slaughtered. The lush green valley of the “daughter of the stars” turned into a smoldering, burning hell. Fires glowed across the valley floor day and night, as great pillars of smoke rose everywhere to cloud an otherwise blue, brilliant fall sky. So severe and wanton was the destruction, the people of the valley would, for decades, refer to this time simply as “The Burning.”

However, as he did so, he set about performing the other job he had been assigned by Grant at the beginning of the campaign: destroying the Confederacy’s source of supply in the Shenandoah. Sheridan’s army methodically and systematically put the Shenandoah Valley to the torch. Crops, barns, and grain stores were burned, and any livestock that the army did not need for its own subsistence were mercilessly slaughtered. The lush green valley of the “daughter of the stars” turned into a smoldering, burning hell. Fires glowed across the valley floor day and night, as great pillars of smoke rose everywhere to cloud an otherwise blue, brilliant fall sky. So severe and wanton was the destruction, the people of the valley would, for decades, refer to this time simply as “The Burning.”

In his report of October 7, Sheridan would report to Grant, detailing the results of his men’s handiwork:

I have the honor to report my command at this point to-night. I commenced moving back from Port Republic, Mount Crawford, Bridgewater, and Harrisonburg yesterday morning. The grain and forage in advance of these points up to Staunton had previously been destroyed. In moving back to this point the whole country from the Blue Ridge to the North Mountains has been made untenable for a rebel army. I have destroyed over 2,000 barns filled with wheat, hay, and farming implements; over seventy mills filled with flour and wheat; have driven in front of the army over 4,000 head of stock, and have killed and issued to the troops not less than 3,000 sheep. This destruction embraces the Luray Valley and Little Fort Valley, as well as the main valley…When this is completed the Valley, from Winchester up to Staunton, ninety-two miles, will have but little in it for man or beast.

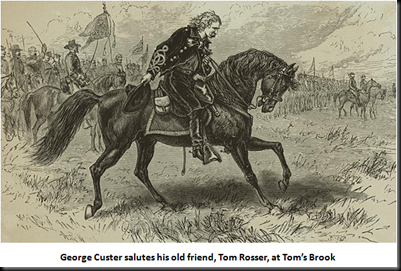

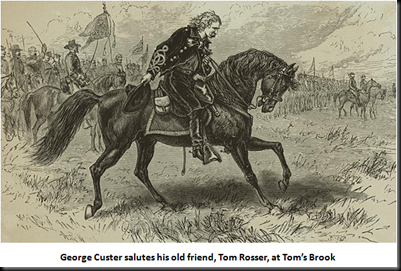

As Sheridan moved north, Early began to trail him, and sent his newly assigned cavalry under General Tom Rosser to keep close watch on and harass the Union army. After a few days, Sheridan grew tired of Rosser’s activities and sent two divisions of his cavalry to deal with him, telling General Torbert, to ‘whip the rebel cavalry or get whipped.” Torbert took Sheridan’s tasking to heart and, on October 9, smashed Rosser’s cavalry at Tom’s Brook. The completeness of the victory was undeniable, as Torbert only lost nine men killed and 48 wounded, while driving Rosser 26 miles to the south and capturing 42 wagons and 52 Confederate prisoners. This victory spawned a nearly universal belief in Sheridan’s army that Early’s Army of the Valley was truly finished.

As Sheridan moved north, Early began to trail him, and sent his newly assigned cavalry under General Tom Rosser to keep close watch on and harass the Union army. After a few days, Sheridan grew tired of Rosser’s activities and sent two divisions of his cavalry to deal with him, telling General Torbert, to ‘whip the rebel cavalry or get whipped.” Torbert took Sheridan’s tasking to heart and, on October 9, smashed Rosser’s cavalry at Tom’s Brook. The completeness of the victory was undeniable, as Torbert only lost nine men killed and 48 wounded, while driving Rosser 26 miles to the south and capturing 42 wagons and 52 Confederate prisoners. This victory spawned a nearly universal belief in Sheridan’s army that Early’s Army of the Valley was truly finished.

Over the next week, Sheridan moved his forces into camp around the Belle Grove Plantation, just north of Cedar Creek and south of the town of Middletown, while Early remained nearby at Fisher’s Hill. Despite this proximity, Sheridan was not overly concerned, so much so that he consented to a journey to Washington to confer with Grant and Secretary of War Stanton on how to extricate his army from the valley and return to the trenches at Petersburg. In everyone’s mind, Jubal Early posed no threat.

Over the next week, Sheridan moved his forces into camp around the Belle Grove Plantation, just north of Cedar Creek and south of the town of Middletown, while Early remained nearby at Fisher’s Hill. Despite this proximity, Sheridan was not overly concerned, so much so that he consented to a journey to Washington to confer with Grant and Secretary of War Stanton on how to extricate his army from the valley and return to the trenches at Petersburg. In everyone’s mind, Jubal Early posed no threat.

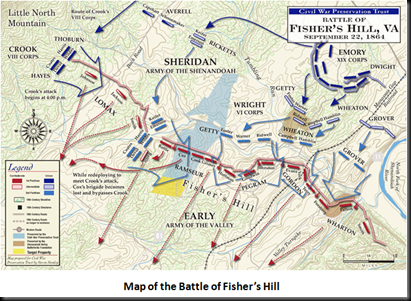

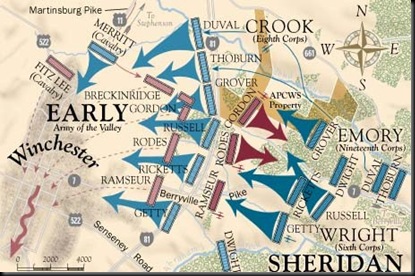

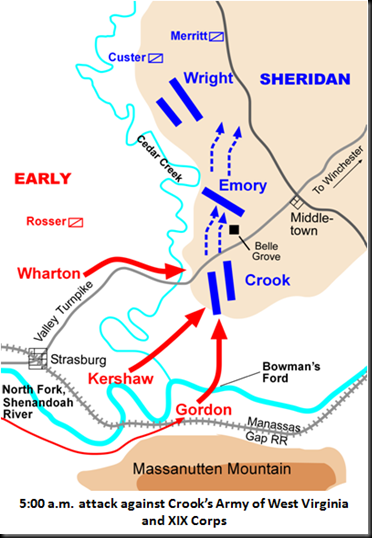

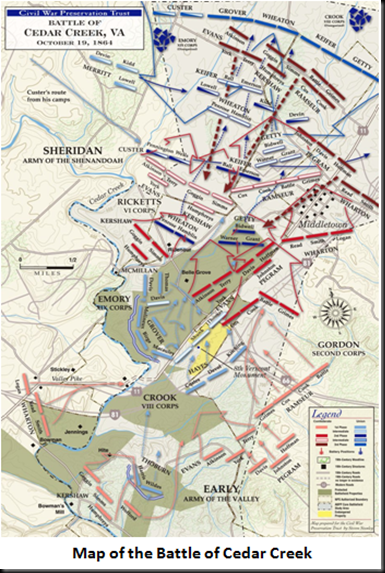

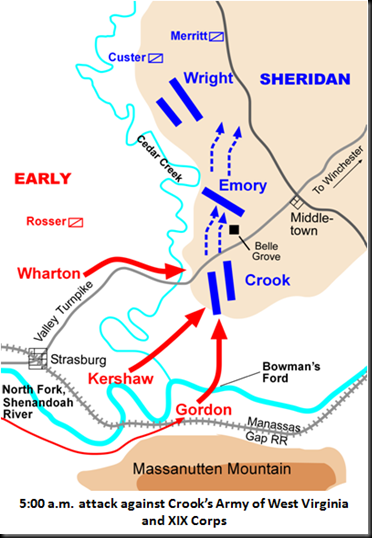

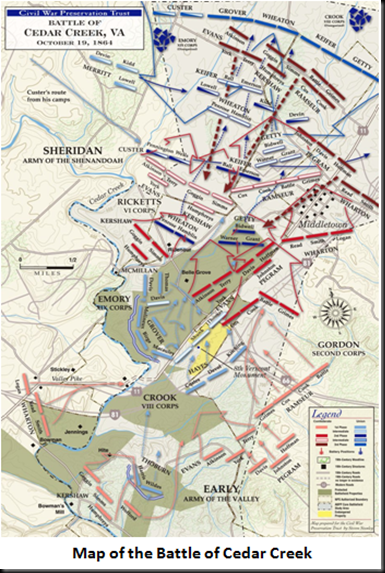

That supreme confidence could be seen in the placement of Sheridan’s army along Cedar Creek. The army was spread over five miles from flank to flank. The cavalry was placed along Back Road, just to the right of VI Corps, which camped on some hills just above the banks of the creek and about a mile northwest of the Valley Pike. XIX Corps sat to their left, occupying a crest about 150 feet above the creek, on which they built entrenchments that ran all the way to the pike. Crook’s Army of West Virginia,  meanwhile was southeast of the pike on a knoll just above the creek, and was the southern terminus of the Union line.

meanwhile was southeast of the pike on a knoll just above the creek, and was the southern terminus of the Union line.

However, as one Union soldier would later remark, “Cedar Creek was a good place to water, but a bad place for a fight.” While there were certain natural strengths to be had in the terrain, there also were significant disadvantages. In the Civil War, being able to mutually support one another was of critical importance to infantry units, and the terrain north of Cedar Creek did not allow that. The ground was filled with deep ravines and rocky ridges that divided infantry commands from one another, and inhibited rapid movement by the flanks. Plus, the overall deployment reflected more of an encampment than a battlefield alignment. However, for the most part, the placement of Sheridan’s army was solid in terms of resisting a frontal assault, especially against VI Corps on the right and XIX Corps in the center. However, if a surprise attack was made against the exposed left flank near the creek, one might roll up the entire army and smash it, a flaw Jubal Early and his commanders would soon discover.

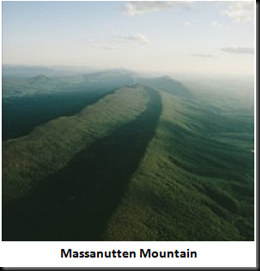

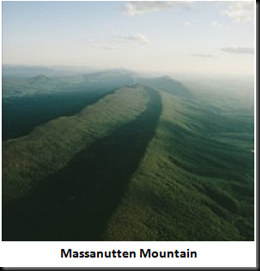

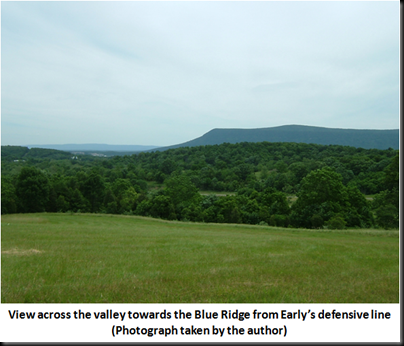

On October 17, John Gordon and Early’s topographical engineer, the legendary Jedediah Hotchkiss, climbed to the top of Signal Knob on the Massanutten of the Blue Ridge to survey Sheridan’s army. From atop the mountain, the Union army was spread before them. The sky was clear and the air cool, with no hint of haze, giving them an unobstructed view. Carefully and methodically mapping the Union emplacements, they could see the opportunity on the Union left, where Crook’s men were encamped and they formulated a daring plan to turn the Union left flank. Returning to Fisher’s Hill that night, they briefed Early on their plan and he approved it. Early would later write in his memoirs that, “I was now compelled to move back for want of provisions and forage or attack the enemy in his position with the hope of driving him from it, and I determined to attack.”

On October 17, John Gordon and Early’s topographical engineer, the legendary Jedediah Hotchkiss, climbed to the top of Signal Knob on the Massanutten of the Blue Ridge to survey Sheridan’s army. From atop the mountain, the Union army was spread before them. The sky was clear and the air cool, with no hint of haze, giving them an unobstructed view. Carefully and methodically mapping the Union emplacements, they could see the opportunity on the Union left, where Crook’s men were encamped and they formulated a daring plan to turn the Union left flank. Returning to Fisher’s Hill that night, they briefed Early on their plan and he approved it. Early would later write in his memoirs that, “I was now compelled to move back for want of provisions and forage or attack the enemy in his position with the hope of driving him from it, and I determined to attack.”

On the night of October 18, the audacious plan was set in motion with all units to be in place by 5:00 a.m. the next morning. Gordon's, Ramseur's, and Pegram's divisions, were placed under Gordon’s overall command and left Fisher’s Hill, moving toward the Blue Ridge. Turning north, they followed a narrow path along the face of the Massanutten, a “pig’s path,” marching in single file. The moon was bright and dimly lit the small path. Gordon carefully placed couriers at ever fork in the pathway, making sure that the troops went in the right direction as they stealthily approached the Union lines. As they neared the point of attack, a dense fog and mist began to form along the creek, allowing them to sneak up on and capture Federal pickets. By 4:00 a.m., Gordon’s men were ready.

Meanwhile, Kershaw's and Wharton's divisions, along with what remained of Early’s artillery, advanced down the Valley Pike, by Spangler's Mill and through Strasburg. Kershaw's column diverged to the right on the road to Bowman's Mill Ford, where it prepared for the dawn attack. Wharton continued on the pike past the George Hupp House to Hupp's Hill, where he deployed his division. Southern artillery, meanwhile, massed on the Valley Pike south of Strasburg to await orders to fire as the coming battle developed.

Ironically, as all this was taking place, Sheridan was sleeping soundly in Winchester, some thirteen miles to the northeast. He had returned there from the conference in Washington and, seeing no need to quickly return to his command, he opted to spend the night in Winchester. Certain that Early was nowhere near and even more certain that he did not pose a threat, Sheridan was confident that his corps commanders could handle whatever might occur.

As 5:00 a.m. approached, the dense fog still clung to the hills around Cedar Creek and the first shafts of the morning’s light were piercing the eastern sky above the Blue Ridge. Sheridan’s men began to stir, quietly making their breakfast, and the smell of brewing coffee and frying pork fat soon filled the air. Little did they suspect that danger was so very close and what one soldier would describe as “Hell Carnival” was about to begin.

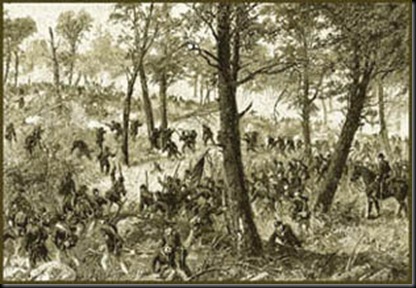

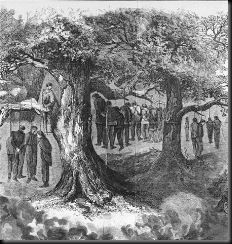

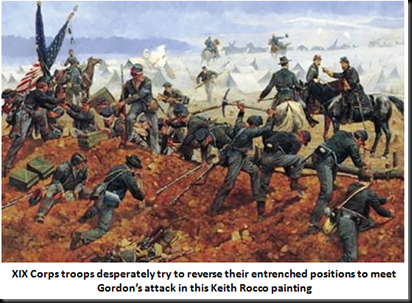

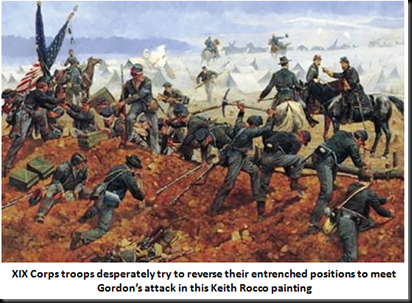

On the Union left, George Crook’s men were squatting by their campfires, pouring coffee, and preparing to eat when a thunderous volley of rifle fire rang out, breaking the still calm of the cool, crisp fall morning. This was followed by the sound of a thousand throats shouting a shrill “rebel yell” and the sight of hundreds of Confederate soldiers charging out of the fog like some nightmarish apparition. Early’s men quickly climbed over the Union entrenchments and poured a merciless volley into the West Virginians, cutting Crook’s men down by the score.

On the Union left, George Crook’s men were squatting by their campfires, pouring coffee, and preparing to eat when a thunderous volley of rifle fire rang out, breaking the still calm of the cool, crisp fall morning. This was followed by the sound of a thousand throats shouting a shrill “rebel yell” and the sight of hundreds of Confederate soldiers charging out of the fog like some nightmarish apparition. Early’s men quickly climbed over the Union entrenchments and poured a merciless volley into the West Virginians, cutting Crook’s men down by the score.

Union officers dashed about, trying to form up their surprised men and resist the attackers. But, these initial attempts were quickly overrun. Crook’s men began to flee in disorder and one of his division commanders, General Thoburn, was killed trying to rally his men. A few regiments did manage to form up and one, the 11th West Virginia, was able to resist long enough to allow some of the artillery to get away. However, the remainder of Crook’s command made a mad dash for the rear.

At the sound of firing on their right, Wharton's division advanced and Early’s artillery opened a steady barrage fire on the XIX Corps from the heights overlooking Cedar Creek. However, almost immediately, Gordon’s attack on the Union left began to lose some cohesion as starving, poorly clothed Confederate soldiers stopped to pillage the Union camps, grabbing up food, blankets, and shoes wherever they could find them. Confederate officers desperately tried to restore order and soon had their men moving again.

Meanwhile, mobs of stragglers from Crook's command streamed west across the Valley Pike, confirming the scope of the disaster. Seeing this, Emory withdrew his XIX Corps units that covered the turnpike bridge and attempted to form a defensive line parallel with the pike. As he did so, Wharton's division attacked across Cedar Creek capturing seven Union guns. Several Federal brigades made a stand against Wharton that gave Union supply wagons parked near Belle Grove Plantation enough time to escape to the north. However, that was all the resistance they could muster, as Early’s men pushed them steadily backward toward Belle Grove.

As Crook’s army evaporated and XIX Corps fell back, VI Corps deployed to meet the approaching assault, forming a line anchored on Cedar Creek and fighting an isolated battle against Kershaw's division. Wheaton's Division of VI Corps advanced to high ground in the fields north of Belle Grove, where they were assaulted by Gordon. As the sun rose in the sky and burned off the dense fog, the two sides could see each other for the first time, and Union resistance stiffened. Kershaw and Gordon repeatedly battered themselves against VI Corps until the Federals finally began a slow but organized retreat toward Middletown. While Early’s attack was still moving forward, the stubborn defense mounted by VI Corps had broken his momentum and was, even now, allowing Sheridan’s army to regroup. Worse, the plundering of the now abandoned Union camps continued, which further slowed the Southern advance and added to the steady loss of precious momentum.

As Crook’s army evaporated and XIX Corps fell back, VI Corps deployed to meet the approaching assault, forming a line anchored on Cedar Creek and fighting an isolated battle against Kershaw's division. Wheaton's Division of VI Corps advanced to high ground in the fields north of Belle Grove, where they were assaulted by Gordon. As the sun rose in the sky and burned off the dense fog, the two sides could see each other for the first time, and Union resistance stiffened. Kershaw and Gordon repeatedly battered themselves against VI Corps until the Federals finally began a slow but organized retreat toward Middletown. While Early’s attack was still moving forward, the stubborn defense mounted by VI Corps had broken his momentum and was, even now, allowing Sheridan’s army to regroup. Worse, the plundering of the now abandoned Union camps continued, which further slowed the Southern advance and added to the steady loss of precious momentum.

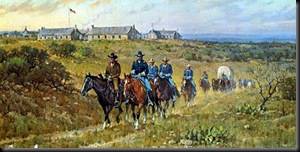

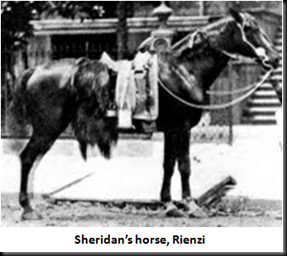

As soon as the artillery had begun to fire at Cedar Creek, a distant, steady rumble could be heard in Winchester. Pickets reported the sound of steady firing to Sheridan, but, at first, as he arose from bed, the Union general was none too worried. Soon, however, a staff officer entered Sheridan’s bedroom and told him that the firing to the south was continuing. The general ordered that his breakfast be quickly prepared and his horse, Rienzi, saddled.  Rienzi was a beautiful, black six-year old Morgan that stood 17 hands high, easily dwarfing the diminutive Sheridan. By 8:30, Sheridan had finished his breakfast, mounted Rienzi, and begun a slow trot through the streets of Winchester toward Middletown.

Rienzi was a beautiful, black six-year old Morgan that stood 17 hands high, easily dwarfing the diminutive Sheridan. By 8:30, Sheridan had finished his breakfast, mounted Rienzi, and begun a slow trot through the streets of Winchester toward Middletown.

Upon reaching the southern limits of Winchester, the firing could clearly be heard in the distance as “an unceasing roar.” Sheridan listened carefully for a few moments, then spurred Rienzi forward down the road. Within a few miles, he came upon the first evidence of the mounting disaster at Cedar Creek in the form of stalled, tangled wagons driven by members of Crook’s command. They told Sheridan that all was near ruin, prompting the general to send his staff forward at a gallop in an effort to sort out what was happening ahead.

They quickly returned to tell Sheridan that they came upon more men who were telling the same story, one of defeat and a panicked rout. Sheridan now set off at a gallop towards the fighting, shouting at every group of dispirited soldiers to follow him and get back in the fight. To one group, he exclaimed, “Boys turn back; face the other way. I am going to sleep in that camp tonight or in hell!” Reading those words some 145 years distant from the event, one may see them somewhat cynically as pointless bravado. However, they proved to be a magic elixir to these frightened Union soldiers. Hearing Sheridan’s words, men cheered, turned around, and headed back into battle. As he galloped south along the Valley Pike, the tide of men flowing north in retreat turned and reversed itself.

They quickly returned to tell Sheridan that they came upon more men who were telling the same story, one of defeat and a panicked rout. Sheridan now set off at a gallop towards the fighting, shouting at every group of dispirited soldiers to follow him and get back in the fight. To one group, he exclaimed, “Boys turn back; face the other way. I am going to sleep in that camp tonight or in hell!” Reading those words some 145 years distant from the event, one may see them somewhat cynically as pointless bravado. However, they proved to be a magic elixir to these frightened Union soldiers. Hearing Sheridan’s words, men cheered, turned around, and headed back into battle. As he galloped south along the Valley Pike, the tide of men flowing north in retreat turned and reversed itself.

At 10:30 a.m., Sheridan arrived on the field. Seeing him, the men of VI Corps broke out into wild cheers at the return of ‘Little Phil.” Sheridan dismounted and met with his corps commanders. When General Emory reported that XIX Corps had reorganized and could cover a retreat to Winchester, Sheridan angrily turned to him and shouted, “Retreat–Hell! We’ll be back in our camps tonight!” With that, Sheridan began reorganizing the army and preparing for a counterattack. VI Corps was deployed on the left of the line, adjacent to the Valley Pike, with XIX Corps on the right. Crook's shattered and disorganized command was placed in reserve. As the two sides continued skirmishing, Sheridan completed his reorganization by placing a cavalry division on each of his flanks, with Merritt on the left and Custer on the right.

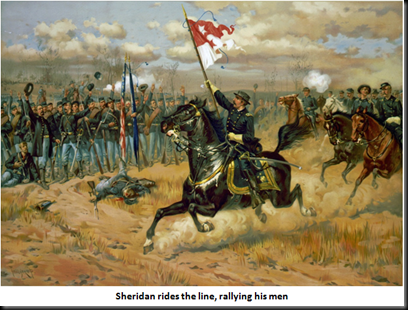

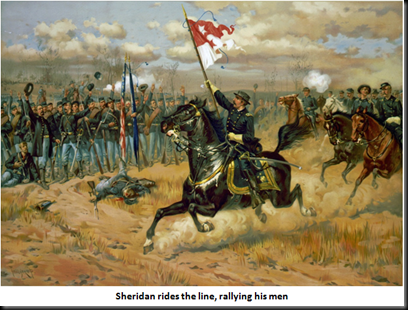

By 3:00 p.m., all was in place for the Union counterattack. However, first, in one of the most dramatic moments of the war, Sheridan again mounted Rienzi and rode along the front of the reestablished Federal battle line, between his men and Early’s Confederates. The Union soldiers responded with a tremendous cheer as Sheridan rode up and down their line. This was the kind of inspiring physical bravery often required of commanders during the Civil War and, in this case, its effects were almost magical.

By 3:00 p.m., all was in place for the Union counterattack. However, first, in one of the most dramatic moments of the war, Sheridan again mounted Rienzi and rode along the front of the reestablished Federal battle line, between his men and Early’s Confederates. The Union soldiers responded with a tremendous cheer as Sheridan rode up and down their line. This was the kind of inspiring physical bravery often required of commanders during the Civil War and, in this case, its effects were almost magical.

As the afternoon wore on, Jubal Early became convinced that he had won a great victory and that Federal forces would retire as soon as nightfall arrived. He could not have been more wrong. Shortly after 3:00 p.m., Merritt’s Union cavalry began advancing from the Federal left, pressuring Early’s right flank north of Middletown. At the same time, George Custer maneuvered his men into position on the Union right flank, opposite Gordon's men. Thirty minutes later, Custer's division of cavalry along with infantry from XIX Corps attacked Early’s vulnerable left flank. The assault quickly overran and scattered Gordon's entire division. Within minutes, Early’s Army of the Valley, so flush with apparent victory, unraveled from west to east.

Map image used with permission by the Civil War Preservation Trust

Map image used with permission by the Civil War Preservation Trust

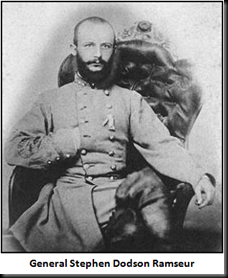

As Gordon’s men fled, Sheridan ordered a general advance of VI Corps and the remainder of XIX Corps. As the blue wave surged forward, Sheridan rode among his men, waving his hat, shouting, “Give them hell!” and ‘Put a twist on ‘em!” The fighting in the center of the line soon grew fierce and Ramseur's division stubbornly resisted in the center, despite the fact that both Kershaw and Gordon had abandoned his flanks. As the fighting raged, young Ramseur fell mortally wounded from his horse while leading his men. With this, Confederate resistance completely collapsed and another hasty retreat began. Early’s men were able to fight a delaying action in the rear as the army fell back in fairly good order, up the Valley Pike, through the Union camps they had captured in the morning, and eventually back across Cedar Creek. Union cavalry now joined the pursuit and pressured Early’s army even after nightfall, finally ending the chase when the shattered Southern army once again reached Fisher’s Hill. With that, the fight for the Shenandoah Valley was at an end.

That night, Union soldiers did, indeed, return to their camps. On the lawn in front of Belle Grove, a bonfire was lit, as Sheridan and his officers celebrated. They all congratulated the bandy Irishman and, in fact, the praise was deserved. This victory was truly Sheridan’s, as he had wrested it literally from the jaws of defeat using his own charisma, courage, and tenacity.

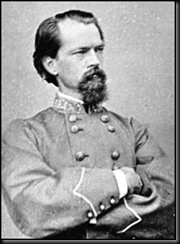

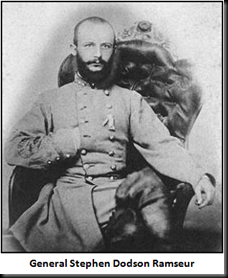

But, a few yards away inside Belle Grove, a different story was being played out. There, in the main floor library, Union surgeons battled to save the life of one of their enemies, 27-year old General Stephen Dodson Ramseur. But, the wound to his lungs was too severe for their skills to overcome. Ramseur lay on a bed, dying. While in the Shenandoah, his wife had given birth back home to their first child, and he had longed for the furlough that would allow him to see them both. Now, that would never come. His old friends from West Point, George Custer among them, came to his bedside, talking to him, providing what comfort they could. In his last conscious moments, Ramseur asked that a lock of his hair be sent to his wife and the new baby he would never see. Early on the morning of October 20, he died and, while he was in a Union hospital, he still died among his friends.

But, a few yards away inside Belle Grove, a different story was being played out. There, in the main floor library, Union surgeons battled to save the life of one of their enemies, 27-year old General Stephen Dodson Ramseur. But, the wound to his lungs was too severe for their skills to overcome. Ramseur lay on a bed, dying. While in the Shenandoah, his wife had given birth back home to their first child, and he had longed for the furlough that would allow him to see them both. Now, that would never come. His old friends from West Point, George Custer among them, came to his bedside, talking to him, providing what comfort they could. In his last conscious moments, Ramseur asked that a lock of his hair be sent to his wife and the new baby he would never see. Early on the morning of October 20, he died and, while he was in a Union hospital, he still died among his friends.

In the years following the war, Cedar Creek enjoyed great notoriety and was, arguably, as famous as Gettysburg or Shiloh. The Northern public’s imagination was captured by the story of a defeat turned into victory by Sheridan’s magnificent ride on Rienzi up the Valley Pike. It became immortalized by poet Thomas Buchanan Read, who wrote the poem “Sheridan’s Ride” a few months after the battle. The poem was printed in almost all the basic school readers of the late 19th century and it has often been said that there wasn’t a schoolboy north of the Mason-Dixon Line who did not memorize its dramatic passages.

On a personal note, I would like to add that this campaign and its battles have long held great interest for me because three of my ancestors served under Sheridan in the Valley Campaign and fought at Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and, finally, at Cedar Creek. My great-great grandfather, George W. Shimer was a sergeant in Company C, 11th West Virginia Infantry Regiment, which was a part of Thoburn’s division of Crook’s Army of West Virginia. He served in the valley alongside his lifelong friend and another great-great grandfather,

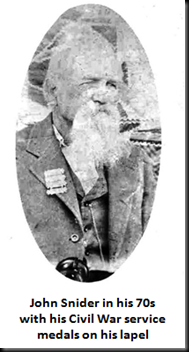

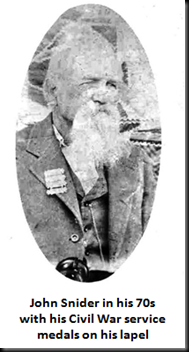

On a personal note, I would like to add that this campaign and its battles have long held great interest for me because three of my ancestors served under Sheridan in the Valley Campaign and fought at Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and, finally, at Cedar Creek. My great-great grandfather, George W. Shimer was a sergeant in Company C, 11th West Virginia Infantry Regiment, which was a part of Thoburn’s division of Crook’s Army of West Virginia. He served in the valley alongside his lifelong friend and another great-great grandfather,  John Snider, who was a private in Company C. Both men would muster out in December 1864, and return home to their families. While they would spend the rest of their lives in peace, raising their families and working their farms in the mountains of West Virginia, they both were active members of the Grand Army of the Republic, the fraternal organization of Union veterans. For his part, John Snider would remember his service in the valley by naming his first son Benjamin “Sheridan” Snider. In fact, in the only photograph I have of him, taken when he was in his seventies, he is still proudly wearing his service medals.

John Snider, who was a private in Company C. Both men would muster out in December 1864, and return home to their families. While they would spend the rest of their lives in peace, raising their families and working their farms in the mountains of West Virginia, they both were active members of the Grand Army of the Republic, the fraternal organization of Union veterans. For his part, John Snider would remember his service in the valley by naming his first son Benjamin “Sheridan” Snider. In fact, in the only photograph I have of him, taken when he was in his seventies, he is still proudly wearing his service medals.

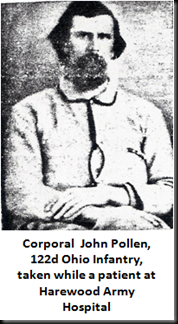

Meanwhile, my great-great-great uncle, James Pollen, also served in the valley. He was George Shimer’s brother-in-law and a corporal in the 122d Ohio Infantry Regiment of Rickett’s Division of VI Corps. When he arrived in the Shenandoah, he was already a veteran, having fought at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and Monocacy. At Cedar Creek, he was wounded by a Confederate bullet that entered and exited his right forearm, luckily not damaging any bone as it passed through.  He would be sent to Harewood Army Hospital in Washington to be treated and recuperate. In February 1865, he was discharged from the hospital and returned to his regiment, which was now outside Petersburg. He would go on to participate in the breakthrough at Petersburg and the pursuit of Lee to Appomattox. On June 28, 1865, he was discharged from the army, given a disability pension, and returned to his family farm in Coshocton County, Ohio.

He would be sent to Harewood Army Hospital in Washington to be treated and recuperate. In February 1865, he was discharged from the hospital and returned to his regiment, which was now outside Petersburg. He would go on to participate in the breakthrough at Petersburg and the pursuit of Lee to Appomattox. On June 28, 1865, he was discharged from the army, given a disability pension, and returned to his family farm in Coshocton County, Ohio.

As a result of the service of these men, my ancestors, I feel I have a personal stake in saving and preserving the fields on which they, their Union comrades, and their brave Confederate foes battled in the Shenandoah Valley. While I realize some would argue that these lands have been paid for and are owned by people who should be rightfully allowed to develop them for commercial use, I would argue that these lands have already been paid for with something far more valuable than mere money. As a result, they are a part of our common heritage as Americans and to allow them to be buried underneath strip malls and houses is criminal. To allow this to happen, denies the sacrifice of those who fought and diminishes us all as a people. Therefore, I would ask all my readers to please support organizations such as the Civil War Preservation Trust in protecting and preserving these remaining pieces of our history. For, if we allow these fields to disappear, we will allow the memories they hold to disappear was well.

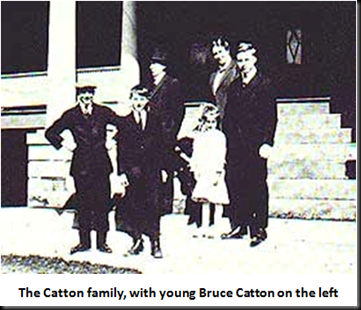

Who is your favorite Civil War historian? I have several historians whose works I always look for on the book store’s shelves, including James McPherson, Jeffry Wert, Gary Gallagher, and William C. Davis. However, one historian holds a special place in my heart: the late Bruce Catton. As a boy, his were the first histories I read and he had an amazing talent for bringing the people and events of the Civil War era alive. I realize that for many younger readers that name may not be as familiar as the other, more contemporary luminaries I listed. With the passage of time since his death in 1978, Bruce Catton's books no longer fill the shelves as they once did. But, at one time, Catton was, arguably, the most popular writer of Civil War histories.

Who is your favorite Civil War historian? I have several historians whose works I always look for on the book store’s shelves, including James McPherson, Jeffry Wert, Gary Gallagher, and William C. Davis. However, one historian holds a special place in my heart: the late Bruce Catton. As a boy, his were the first histories I read and he had an amazing talent for bringing the people and events of the Civil War era alive. I realize that for many younger readers that name may not be as familiar as the other, more contemporary luminaries I listed. With the passage of time since his death in 1978, Bruce Catton's books no longer fill the shelves as they once did. But, at one time, Catton was, arguably, the most popular writer of Civil War histories.  Catton was born October 9, 1899 in Petoskey, Michigan, but grew up in the small community of Benzonia in the northwestern part of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. The son of a Congregationalist minister, young Bruce first learned about the war through the reminiscences of the aged veterans of his town who had fought in the Civil War. Their stories made a lasting impression upon him, and all his work seems to have been, in some way, an attempt to maintain the connection they provided to that time in their youth and the faith which sustained them during this great American tragedy:

Catton was born October 9, 1899 in Petoskey, Michigan, but grew up in the small community of Benzonia in the northwestern part of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. The son of a Congregationalist minister, young Bruce first learned about the war through the reminiscences of the aged veterans of his town who had fought in the Civil War. Their stories made a lasting impression upon him, and all his work seems to have been, in some way, an attempt to maintain the connection they provided to that time in their youth and the faith which sustained them during this great American tragedy: In 1951, he published Mr. Lincoln’s Army, the first volume in what would become a trilogy about the Union’s Army of the Potomac. A year later, the second volume, Glory Road, would hit the bookshelves and readers began to see something new in his writing. Here was an author who, while detailing the major historical events and figures of the time, still delved into the life, death, and experience of the soldier in the line. For Catton, the story of the war was as much about the private as the general, and, perhaps, even more so. As a result, his books contained a unique humanity about them that most historians failed to provide and this remarkable quality resonated with his growing population of followers, many

In 1951, he published Mr. Lincoln’s Army, the first volume in what would become a trilogy about the Union’s Army of the Potomac. A year later, the second volume, Glory Road, would hit the bookshelves and readers began to see something new in his writing. Here was an author who, while detailing the major historical events and figures of the time, still delved into the life, death, and experience of the soldier in the line. For Catton, the story of the war was as much about the private as the general, and, perhaps, even more so. As a result, his books contained a unique humanity about them that most historians failed to provide and this remarkable quality resonated with his growing population of followers, many  of whom had been privates themselves in World War II.

of whom had been privates themselves in World War II. He certainly lived up to that challenge. He would continue to write for American Heritage while producing more books on the Civil War, including the three-part Centennial History of the Civil War (The Coming Fury, Terrible Swift Sword, and Never Call Retreat) published in 1961, 1963, and 1965; a two-volume work on Ulysses S. Grant (Grant Moves South and Grant Takes Command), published in 1960 and 1968; and This Hallowed Ground, a history of the war told from the Union perspective, which received a Fletcher Pratt award in 1957. In 1959, he would be named senior editor of American Heritage, a post he held for the rest of his life.

He certainly lived up to that challenge. He would continue to write for American Heritage while producing more books on the Civil War, including the three-part Centennial History of the Civil War (The Coming Fury, Terrible Swift Sword, and Never Call Retreat) published in 1961, 1963, and 1965; a two-volume work on Ulysses S. Grant (Grant Moves South and Grant Takes Command), published in 1960 and 1968; and This Hallowed Ground, a history of the war told from the Union perspective, which received a Fletcher Pratt award in 1957. In 1959, he would be named senior editor of American Heritage, a post he held for the rest of his life. Catton was an author and historian who “made us hear the sounds of battle and cherish peace.” I believe, however, Bruce Catton did far more than that. He approached his work with such an intense devotion because he saw a greater story in the Civil War than one merely of great men and titanic battles, and a greater lesson for the nation and the generations that would follow. He saw the war as the first chapter of a story that might never end and one that posed a challenge for all of us who would follow as Americans. In his 1958 book, America Goes to War, Catton titled the final chapter, “The Heritage of Victory.” In the closing pages he wrote that all Americans, both north and south, had failed to understand the real meaning of the war:

Catton was an author and historian who “made us hear the sounds of battle and cherish peace.” I believe, however, Bruce Catton did far more than that. He approached his work with such an intense devotion because he saw a greater story in the Civil War than one merely of great men and titanic battles, and a greater lesson for the nation and the generations that would follow. He saw the war as the first chapter of a story that might never end and one that posed a challenge for all of us who would follow as Americans. In his 1958 book, America Goes to War, Catton titled the final chapter, “The Heritage of Victory.” In the closing pages he wrote that all Americans, both north and south, had failed to understand the real meaning of the war:

By 3:00 p.m., all was in place for the Union counterattack. However, first, in one of the most dramatic moments of the war, Sheridan again mounted Rienzi and rode along the front of the reestablished Federal battle line, between his men and Early’s Confederates. The Union soldiers responded with a tremendous cheer as Sheridan rode up and down their line. This was the kind of inspiring physical bravery often required of commanders during the Civil War and, in this case, its effects were almost magical.

By 3:00 p.m., all was in place for the Union counterattack. However, first, in one of the most dramatic moments of the war, Sheridan again mounted Rienzi and rode along the front of the reestablished Federal battle line, between his men and Early’s Confederates. The Union soldiers responded with a tremendous cheer as Sheridan rode up and down their line. This was the kind of inspiring physical bravery often required of commanders during the Civil War and, in this case, its effects were almost magical.

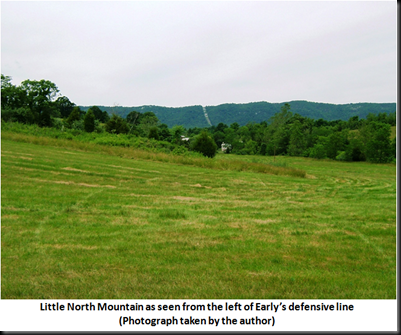

However, at first, Early was not overly concerned about his left flank because Lomax's position was at the base of the steep, rough terrain of Little North Mountain. As a result, he probably felt confident that no Union force could realistically threaten his left. Plus, he had a commanding view from atop the hill and his artillery covered every possible approach. One Southern officer referred to the Fisher’s Hill defenses as “our Gibraltar.” However, Early began to worry his position was not so impregnable. He realized that, while his position was impressive, he no longer had enough men to man the line. With his casualties at Winchester, his effective strength was reduced to about 10,000 men. As he rode his line, he realized how thin it truly was. By the afternoon of September 22, “Old Jube” had decided to abandon Fisher’s Hill, issuing an order for a nighttime retreat up the valley. However, his decision to fall back came too late.

However, at first, Early was not overly concerned about his left flank because Lomax's position was at the base of the steep, rough terrain of Little North Mountain. As a result, he probably felt confident that no Union force could realistically threaten his left. Plus, he had a commanding view from atop the hill and his artillery covered every possible approach. One Southern officer referred to the Fisher’s Hill defenses as “our Gibraltar.” However, Early began to worry his position was not so impregnable. He realized that, while his position was impressive, he no longer had enough men to man the line. With his casualties at Winchester, his effective strength was reduced to about 10,000 men. As he rode his line, he realized how thin it truly was. By the afternoon of September 22, “Old Jube” had decided to abandon Fisher’s Hill, issuing an order for a nighttime retreat up the valley. However, his decision to fall back came too late.